Friday, November 30, 2018

Thursday, November 29, 2018

Wednesday, November 28, 2018

Bill Williams – Comic Artist

by John Adcock

Bill Williams was an exceptional cartoonist and ink-slinger. Alfred Owen “Bill” Williams was born on May 22, 1918 in South Bend, Indiana. Bill’s grandfather Jonathan Williams was born into a Quaker family in Hamilton County, Indiana in 1840. His father worked for Clark Equipment and is credited with developing the gasoline powered forklift. Bill enrolled in the school of architecture at the University of Michigan in the late thirties, only to drop out to work for the Walt Disney Studios in Hollywood. He worked on Fantasia, Dumbo and The Reluctant Dragon before enlisting in the Army Air Corps, serving in the Pacific during world War II. He received the Air Medal and Oak Leaf Clusters for distinguished service in air combat. Williams returned for a short time to Disney then moved to New York where he drew a single-panel cartoon called Dolly, syndicated in 187 newspapers. He died November 10, 1986. Services were held in Old Lyme, Connecticut.

|

| [1] GI Jane advertisement, Bill Williams, 1955 |

People in

the news.

In an interview, cartoonist Alfred O. Williams of Wilton spoke about

his days working for Walt Disney when he did the penciling part of animation

productions. His subjects were Donald Duck, Pluto, Goofy and others. Among the

animated feature films he worked on were Fantasia and Dumbo. He also did

layouts for MGM for the Tom and Jerry series and Hanna and Barbera.

|

| [2] Henry Aldrich No. 22, Sept/Oct 1954 |

|

| [3] Farmer's Daughter Feb/Mar 1954 |

|

| [4] G.I. Jane, Hal Seeger and Bill Williams, 1954 |

|

| [5] First issue of Kookie, Bill Williams |

|

| [6] Advertisement. Bill Williams |

|

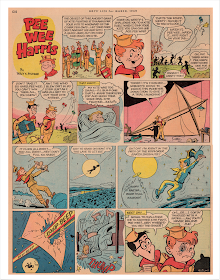

| [7] Pee Wee Harris, Bill Williams, March 1959 |

|

| [8] Boy's Life, Bill Williams, March 1959 |

|

| [9] Farmer's Daughter Feb/Mar 1954 |

|

| [10] Dunc & Loo, Oct/Dec 1961 |

|

| [11] PX Pete, Bill Williams, GI Jane 1954 |

|

| [12] Boy's Life illustration, July 1957 |

Thanks to Skip Higgins for additional biographical information.

❦❦❦

Tuesday, November 27, 2018

Monday, November 26, 2018

A Crowded Life in Comics – Werner Wejp-Olsen

The Cartoonist Known As WOW

by Rick Marschall

This week we lost a favorite international cartoonist, Werner

Wejp-Olsen. His years were 1938-2018, and his residences were Denmark-United

States-Denmark. I want to pay tribute to a friend and a good cartoonist, and

share how friendships can grow into mutual friendships, and connections, and

networking, and new career paths.

That’s how life is supposed to work. And in cartooning, which I

think has a greater percentage of good people than most professions, it happens

a lot.

Werner (the “Wejp” part of his name is pronounced “Wipe” but with

a soft “v,” unless the Dane is eating herring when making the explanation, and

then all bets are off) started drawing professionally when he was still in high

school, for Ekstra Bladet, around 1955. He signed his humor strips and

cartoons WOW. A dozen years later he drew the continuing series Peter and Perle;

and in 1972 inherited the popular Felix from Swedish cartoonist Jan Lööf.

Ever creative and entrepreneurial, Werner created the flagship of

his several quiz and puzzle type features, Dick Danger; and in 1974 the

strip Fridolin. It was at this stage of his career that Werner

intentionally adopted into his style what he called “the Connecticut School” –

a term that entered the language of Scandinavian cartoon – the “bigfoot,”

rounded, somewhat minimalist humor style of Mort Walker, Dik Browne, and their

fellows.

I met Werner when I was Comics Editor of Publishers Newspaper Syndicate

(Field Enterprises) in 1975. The syndicate president Dick Sherry had a penchant

for foreign cartoonists, which he presented as a cosmopolitan reach, but which

we all knew, sub rosa, was his excuse to make one or two overseas trips

a year “on syndicate business.” England, Australia, Italy, Scandinavia…

As an editor who was not consulted on these “finds,” I usually was

less than enthusiastic, and so were American editors, as it turned out. But the

promotion department was kept active, and so were international airlines.

Nevertheless, Werner was flown over to Chicago for strategy

sessions, promo art, and such. We hit it off immediately – especially when he

learned that I moved to Chicago from Fairfield County, Connecticut; and that

several of his cartooning gods were close friends, some even having attended my

wedding only months previous.

I will mention a couple of strips that have not been cited in any

of the obituary articles around the world. One was a suburban family strip –

not an automatic challenge for a Danish cartoonist; on my several trips to

Denmark I have noticed that the Danish sense of humor, and its lifestyle,

especially in suburban neighborhoods, is closer to the Americans than in other

lands I have visited. The name of the strip was Zip Cody, a pun on ZIP

Code.

It proved a wet match, attracting only 25 newspapers as I recall.

Although this was Dick Sherry’s “baby” I suggested that the aggressive,

no-nonsense grandmother – she invariably chomped on a cigar butt, and was not

the strongest, but the only, standout personality in the cast. Otherwise it was

basically another follower of Blondie, Dotty Dripple, The

Berrys, Priscilla’s Pop, etc. So the strip was rechristened as Granny

and Slowpoke, her sarcastic-thinking dog sharing the billing.

Unfortunately the client-list dropped further. Despite Jud Hurd’s nice

boost in Cartoonist PROfiles magazine, it was not to be.

Another attempt from Werner’s pen, almost concurrent and at

Publishers too, was a strip whose cast lived in the wings of an operatic

theater. Within the bounds of Werner’s firm pen lines, there was a daffy

quality to the strip. The Maestro and Amalita. It was close to

screwball, with frustrated conductor, the Brunhilde-proportioned diva, and

group of assorted crazy singers, stagehands, and supernumeraries.

This, sadly, was unsuccessful also. At the time – and after I left

the syndicate – I told Werner (diplomatically but sincerely) that the gags were

slightly awkward, and the dialog more so. He assumed I mean that his “ESL” English

was the stumbling-block, and wouldn’t I be surprised to learn that an

English-speaker actually ghost-wrote both strips. No, I wasn’t surprised; I

figured from the start that Dick Sherry, who had no sense of humor and was an

opera-lover, hoped to feather his nest as a silent partner in the strips.

Werner was in his clutches. I happily note that Granny lived on –

funnier and certainly more successful, back in Denmark’s Ekstrabladet as

Momsemore (I think “Mother-in-Law”). He continued with other strips in

his native Denmark; and moved to California in 1989, to start and self-start

(publishing and distribution) other features. Between the two nations he

produced Viggo Vampire, TRENDZ, Tales of Hans Christian

Andersen, Inspector Danger’s Crime Quiz, Professor Yuk-Yuk’s

Cartooning Class, and other books and features including editorial cartoons

and a how-to-draw book. I don’t think there was a time in his career that he

was not busy, and producing several creations simultaneously.

My friendship with Werner continued, including a great visit to

his studio and home in (yes, suburban Copenhagen) Nivå. It is a charming small

town on Denmarks’s largest island, Sjælland; and is a station on the Copenhagen–Helsingør rail line. The tug of

127 varieties of herring, or one of myriad other ancestral attachments, saw

Werneer and his wife Inge move back to Denmark a few years ago.

A happy coincidence was the friendship I made through Werner, that

of Jørgen Sonnergaard, a brilliant (and also constantly active) editor, translator,

author of novels, especially crimes stories, and of comics. He translated many

of the Tintin books into Danish. After working as editor of PIB Service,

he was Chief Editor at Gutenberg Publishing Service in charge of new Disney

releases in Europe, beginning in 1975.

It was there that the coincidence set in, because Dik Browne asked

me to write the script for one of the Hagar the Horrible graphic novels.

I did so – Hagar, King of England was the title – and it was done for

Gutenberghus/Egmont in Denmark, and their subsidiaries throughout Scandinavia,

Germany, and England. And my editor was Werner’s friend, and my earlier

acquaintance Jørgen.

|

| [4] Werner Wejp-Olsen |

There was nothing rotten in Denmark. I wrote the Hagar graphic

novel just before starting as Editor with Marvel; and when I left Marvel,

Jørgen offered me the opportunity to write scripts for Disney comic stories –

Gutenberghus had the license for the same lands where they published Hagar books.

This I did, happily, for several years, writing approximately 30 pages a week.

Every month their editors flew to New York City, stay at the Plaza

Hotel, review my finished stories and go through my concepts for the next ones.

Eventually they almost grew bored of monthly flights to New York. I suggested

that they periodically fly me to Copenhagen, which they commenced. For several

years, life with people named Jørgen, Jens, Lars, Mickey, Scrooge, Donald, Chip

and Dale was my “work.”

Not to mention that dinners at Danish restaurants in New York and

of course Copenhagen were easy to take. For my old friend Werner Wejp-Olsen had

introduced me to the joys of wine herring, creamed herring, kippered herring,

herring and onions, herring in tomato sauce, and (believe me) even more

preparations of herring.

Farewell and skål (the toast pronounced “skol”) to the WOW of

cartooning.

❦

17

Sunday, November 25, 2018

Saturday, November 24, 2018

Sunday, November 18, 2018

Sunday With Bugs Bunny

Al Stoffell and Ralph Heimdahl

The MEN BEHIND THE COMICS

In my childhood I used to follow the daily comic strip adventures

of Bugs Bunny in my hometown newspaper the Trail (BC) Daily Times. Finding

information about Al Stoffell (writer) and Ralph Heimdahl (cartoonist) has

always been a near futile chore, perhaps they were unjustly ignored because

they were producing a cartoon “property” rather than illuminating original

characters. I did, however, find a short article that shed some light on their

lives. In the creators’ own words:

Al Stoffell – “Away back thar in 1947, after I had been a

freelance writer, hotel publicity man, newpaper reporter and a lieutenant in

the Navy, I turned up as a handy man in the editorial department of Western

Publishing Co., which had an agreement with Warner Brothers and Newspaper

Enterprise Association to produce a Bugs Bunny Sunday page. One day somebody

gave me a pat on the back and told me I was going to write the Bugs Bunny

Sunday page. My Norwegian friend (Ralph Heimdahl) and I have been at it ever

since.”

Ralph Heimdahl – “I had been teaching for seven years in Minnesota,

six years in a school for the deaf, when I read about a national competition

that Walt Disney was holding to find artists to work for him in California. I

drew up some Mickey Mouses and some Donald Ducks and sent them in. I was

accepted along with eleven other guys in 1937 and we went through the Disney

training.

There was a big strike and I wound up on a farm in Vermont.

While on the farm I created a comic strip called Minnie Sue and Little Haha which I finally sold to an outfit in New York after my

return to California. It wasn’t real successful but it was a nice little Indian

story.”

|

| [1] November 22, 1958 |

|

| [2] September 1, 1959 |

|

| [3] May 14, 1960 |

The Men Behind The Comics: Heimdahl, Stoffell:

Batty About Bugs, R. Terrance Roskin,

Desert Sun, July 12 1976

❦

Eminent Victorian Cartoonists

The author of Eminent Victorian Cartoonists is Dr. Richard Scully, Associate Professor in Modern European History at the University of New England, Armidale, NSW, 2531, Australia. The book, a "labour of love," published by The Political Cartoon Society, is a three volume comprehensive social and biographical history of the Victorian political cartoon from John 'H.B.' Doyle to Sir (John) Bernard Partridge. The three volumes are built to last; beautifully printed in solid boards with a sturdy slipcase.

To date the histories of the British Victorian political cartoon have focused rather narrowly on the gentlemen of Punch; a carryover from the class-dominated establishment snobbery that dictated the acceptable in literature, art and theater throughout the nineteenth century. A seat at the Punch Table was an entrée to high society and a distinguished knighthood. The young du Maurier looked forward to the day “when illustrating for the millions (swinish multitude) à la Phiz and à la Gilbert will give place to real art, more expensive to print and engrave and therefore only within the means of more educated classes, who will appreciate more.”

Nibbling at the edges were the déclassé serio-comic journals, lower-class cousins of the "estimable Punch," embracing "the million" who sought entertainment by the penny or halfpenny: Judy, with her sideline in "Jolly Books", Fun, Moonshine, Figaro, Funny Folks, The Big Budget, Comic Cuts and Ally Sloper's Half-Holiday...

Eminent Victorian Cartoonists widens the scope of study with its emphasis on five of the best of the generally neglected political cartoonists, "The Rivals" of volume II; Matt Morgan, John Proctor, William Henry Boucher, John Gordon Thomson and Fred Barnard. An essential game-changing reference book filled with insightful biography and caricature history.

To date the histories of the British Victorian political cartoon have focused rather narrowly on the gentlemen of Punch; a carryover from the class-dominated establishment snobbery that dictated the acceptable in literature, art and theater throughout the nineteenth century. A seat at the Punch Table was an entrée to high society and a distinguished knighthood. The young du Maurier looked forward to the day “when illustrating for the millions (swinish multitude) à la Phiz and à la Gilbert will give place to real art, more expensive to print and engrave and therefore only within the means of more educated classes, who will appreciate more.”

Eminent Victorian Cartoonists widens the scope of study with its emphasis on five of the best of the generally neglected political cartoonists, "The Rivals" of volume II; Matt Morgan, John Proctor, William Henry Boucher, John Gordon Thomson and Fred Barnard. An essential game-changing reference book filled with insightful biography and caricature history.

Eminent Victorian Cartoonists

is available HERE

JKA

❦

Saturday, November 17, 2018

A Crowded Life in Comics – Stan Lee

❦

“I always thought I’d quit in a couple of years.

But it never seemed to happen…” – Stan Lee

❦

‘Nuff Said: Memories of Stan

Lee

by Rick Marschall

by Rick Marschall

Stan

Lee died this week. As if he were invulnerable like many of his superheroes –

or the usual superheroes, not the Marvel Universe head-cases – many fans likely

thought he would simply live on and on.

He

did, in a way that few others in the comic-book field did. Even Steve Ditko, so

closely linked to Stan and who also died this year, began his career when Stan

was well established. Heck, Stan was a veteran in comics when I was born. Eventual

retrospectives will assess his career as spanning the Adolescent Age (of the

comic-book format, not only readers’ ages) to extravagant SFX Hollywood

exploitation.

There

have been a plethora of tributes and appraisals of Stan this week, starting

within hours of his death. Media canned obits; fans’ fond memories; critics

jumping on his grave before he could even occupy it – carping, criticism,

iconoclasm, deconstruction, revisionism.

I

think Stan’s contributions were enormous, and I can avoid hagiography to say so.

His personality was enormous, and so were his talents and instincts and ego and

modesty. With great power comes great contradictions.

Instead,

I will offer some aspects and anecdotes that might not be found elsewhere. And

they can be added, perhaps, to the assessments other will make in the future. They

are personal, but not mine alone.

I

met Stan when I was Comics Editor of Publishers Newspaper Syndicate in the

mid-1970s. It was in Chicago, in the Sun-Times Building, across the river from

the virtual cathedral known as Tribune Tower. Stan was in town I think as a

guest of Chicago Con, but also to speak with my syndicate’s president Dick

Sherry. Not about a Spiderman strip; another syndicate, another time,

would do that. No, Stan and Dick had been discussing a European-style magazine,

along the lines of Linus, Eureka, or the original Charlie

– new contents, international material, articles, interviews, news, reviews,

all about comics.

I

don’t remember whose idea it was, originally, but Marvel (or Stan himself?) and

Publishers Syndicate would co-produce. A major investor would have been Johnny

Hart (BC and Wizard of Id), who did not join us for lunch or back

at the office. My familiarity with European comics and cartoonists was a major

reason Sherry hired me, and I would have been the editor. The working title

(appropriately random and only vaguely germane) was to be GROG! after

the strange beast in BC. He would have been the magazine’s “mascot.”

We

made dummy copies and got to second base, but never to third or home, for

various and sundry reasons.

But

Stan and I kept in touch. A couple years later, with Chicago (and the third of

the syndicates where I edited comics) in the rear-view mirror, I wrote to Stan

about working for Marvel. I had never been a particular fan of superheroes, which

I did not, um, stress in our correspondence. It seems that it would not have

made a difference, however, because I was indeed hired, but initially to handle

the magazine line – black and white comics, one-shots, “Super Specials,” movie

adaptations, and such. The Hulk was a hit on network TV then, and the

process-color magazine stories I hatched or edited were supposed to be “more

like the TV Hulk.”

Eventually

I was given the privilege of conceiving (with many Stan conferences),

designing, naming, and charting the course of what became EPIC magazine.

This

brief column will correct some of the conceptions and misconceptions about this

Marvel period, and Stan. The Editor in Chief at the time was Jim Shooter, and

he has written some memoir about my hiring, and the birth (and birth-pangs) of EPIC.

I would like to say that I have read and enjoyed these. I would like to say

that, but I cannot, because they are mostly tripe. He wrote that I was hired “cold”

by him, yet I had known and (almost) worked with Stan previously, as I have

related.

The

same with EPIC: it was to be more like Heavy Metal than GROG!,

of course; and I took the position that, like HM and the European

magazines, we would have to grant creators’ rights and sign royalty agreements.

This

argument was resisted in higher echelons at Marvel, of course. Shooter came on

board but was not father to the idea, despite his revisionist history. And it

did happen: in the Marvel Universe, EPIC was the entry-way to royalty

deals. Stan eventually sent me to Europe, to the Lucca Festival principally, to

scout for artists. (Shooter was steamed, just as he complained about my

invitation to lunches and meetings when European publishers came to New York.

But. I had previous relations with many of them; and as one executive said, “We

don’t want to scare them off.”)

Back

to Stan, and some more pertinent things to share. He was, in the office, just

what people saw in conventions and TV commercials. Dashing about in warp-speed.

Gregarious. Yes, nicknames. There were many meetings, and chats, in his office;

but he often came into the office of me and Ralph Macchio, my assistant.

Sometimes business, of course, but – this was cool – sometimes to talk about

nothing. Not quite like Seinfeld, but… old comics, newspaper strips, “what ever

happened to this-or-that old cartoonist” who I might have known. Once when

Burne Hogarth came up to visit me, I took him down to meet Stan, who acted (and

surely was) blown away to meet the Tarzan artist.

If

memory serves, when Tom Batiuk visited New York once (I had edited Funky

Winkerbean at Publishers) he was awed to be in the Marvel offices, and met

Stan. My Connecticut friend Chad Grothkopf (who was my first landlord after I married

Nancy) requested that I arrange an audience with Stan. They had worked together

decades earlier, and were friends whose wives shared the same first name.

Ralph

thought these visits to my desk were out of the ordinary, by Marvel standards;

usually editors were called to his large office if at all. But these were

social calls. One thing he shared I never forgot. Out of the blue, one day he

talked about his early, and surviving, dreams for Marvel: he always held up

Disneyland, the theme parks; and what they represented. Not so much the

characters except “the way Disneyland, the whole Disney thing, is tattooed on

everyone’s brain... There are other cartoons, but Disney is first. There

are other funny animals, but the Disney ones are what people think of.

Mickey Mouse is the most famous character in the world! Disneyland! A whole

city!” I wondered, years later, after Marvel was swallowed by Disney, how

ironic that was to him – maybe bitter, since Stan was long-gone by then.

More

than that, is something I can share, and it seldom is mentioned about Stan. His

instincts. He loved comics as an art form, but never got artsy about it

(believe me, friends here and in Europe can and do) (so do I). By the end of my

time at Marvel, Stan knew little about the Marvel titles or new characters.

Enough – no; actually, not enough – to answer fans’ questions at

conventions. That was the real reason he gave talks with no questions, or arranged

signings alone, with no presentations.

But

he never lost his technical-editing (if I can use that term) chops. As I said,

I had been a cartoonist, had edited comics, churned ‘em out at Marvel after

all; and studied strips. The “Language and Structure,” as my course would be

called as a teacher at SVA. Stan, however, held “classes” every day.

–

How to construct a page? He would explain how to lead the reader’s eye through

a page.

–

Balloon placement? He was brilliant, seeing designs like parts of jigsaw

puzzle, making the reader look here and notice that, via balloons, sound

effects, visual elements, “camera” angles.

Covers

and colors? This was what Stan held onto longest – approving every single

cover. The drawing, usually roughs AND finishes, and especially the colors.

Contrasts and values, logos and figures. He would never merely reject out of

hand; he would correct and show and discuss. By my time, the assembly-line of

cover roughs had Marie Severin execute the final versions for Stan, and her own

talent as well as years-with-Stan, virtually assured their OKs. But there was

almost always one little tweak, at least, and spot-on irrefutable.

Every

chat was like going to school.

Whatever

is said, or speculated, about Stan Lee’s collaborations, what is seldom said

and less often acknowledged is the undeniable effect that such “lessons” – his

instincts, not just about what would make young readers flip – but how

to do it, in a million subtle ways… could not have been lost on Jack Kirby,

Steve Ditko, and others. Even Drawing the Marvel Way does not give a

full impression of the passionate love affair Stan had with the comic-book

page. And his visceral analyses. I would ask John Buscema if he realized the

same things about Stan. “Oh, sure,” he would wave his hand. He acknowledged

picking up countless tips from Stan.

Memorable

characters? Stan created or wet-nursed them; all with his DNA. Strips? He loved

comics, so launched several newspaper strips. Other genres? He loved

humor, as well as teenage, girls, parody, fumetti, and romance themes.

Merchandising, movies, theme parks… we know them all. Astounding, really.

In

one dynamic man, he was what other publishers needed staffs for. He always

seemed a bit uncomfortable in person, however affable, as if fighting eternally

blocked nasal passages; and – during my time – I used to wonder how painful

those hair plugs were. Yet nothing slowed him down. I even remember hearing

that when he moved to Los Angeles, his place was so big that he skated around

on roller skates, even answering the door with them on. True? Even if not, it

fit the man perfectly. Legends imitate life.

In

that regard, finally, one time he bounded into my office, and related an idea

he had for a Silver Surfer story in the planned EPIC. He was full

of life, gesticulating, doing action poses, loudly building to a crescendo ending.

After he left, Ralph Macchio and I looked at each other, rolling our eyes and

stifling laughs. We had the common impression – the story hung on the sort of

speculation that we both had as kids, young kids, and therefore many readers

probably would too; and therefore the pitch seemed mundane, not special.

Eventually

I realized that the story idea, I won’t recount here, was pure Stan. If it was

juvenile… it touched on ordinary fantasies. A good thing. If it was simple… it

meant it was universal. If it was child-like…

…

well, that was Stan Lee. A brilliant child – maybe several brilliant kids

rolled into one – who never lost the joy of childhood. Everything could be fun,

if you dreamed it right, planned it right, told it right, drew it right, and

sold, or shared it, right. At the root of it all, whatever the genre or

project, Stan Lee asked “What if…?”

Topper: Jack Kirby, Fantastic Four, Marvel Treasury Edition, 1976

Bottom: Stan Lee, 1969

Bottom: Stan Lee, 1969

❦

16