Al Capp’s Own Crowded Life and Family

by Rick Marschall

I knew Al Capp better through the conservative movement, in the late 1960s and early ’70s, than through cartooning. Nevertheless this Crowded Life I chronicle led me to interact in several ways and various times with him.

I also knew his brother Elliot Caplin, about whom not enough has

been written in comics histories. Elliot was quiet, taciturn to the extreme;

seldom registering emotion, forever with a pipe clenched between his teeth. He

let his writing do the talking – Elliot, always anonymously, scripted a dozen

or so strips through the decades.

… maybe more; some he co-created; some he scripted; some (like Broom-Hilda)

he lived in a zone between plating a seed and “packaging” a syndicate

presentation. Among the strips with his plots and dialog, or with various

aspects of his fingerprints: Dr. Bobbs; Peter Scratch; Adam

Ames; The Heart of Juliet Jones; Big Ben Bolt; Abbie an’

Slats; Long Sam; On Stage; Encyclopedia Brown; Best

Seller Showcase; Dark Shadows; Buz Sawyer; post-Gray Little

Orphan Annie; and others. More than Allen Saunders and Nick Dallis

combined.

There was a third Capp brother, Jerry. For a while he handled

business affairs for Al, but the L’il Abner creator largely considered

Jerry a hanger-on, and for most of his career he hung around Elliot. Elliot

himself was the quiet center of an active business career beyond his writing.

He was on the staff of Judge magazine (“I put them to bed for good,” he

dead-panned) and then was an editor of Parent’s Magazine. He parlayed

his experience and Al’s success into Toby Press, named for his third child. It

was a comic-book publisher mostly handling Li’l Abner titles.

A fourth Capp I knew, also. When I joined the staff of the Connecticut

Herald out of college, as cartoonist and editor, there was an old fellow

who shuffled through all the rooms every morning, dispensing lollipops to every

desk. He had been with the paper since forever, I was told; probably since the 1930s

in its glory days as The Bridgeport Herald. He was a pleasant old relic

of the sales staff, and when, after a week or two, I became a recipient of

Harry Resnick’s morning lollipops, I knew I had arrived.

Hesch Resnick had served as Al Capp’s agent when, as Alfred G

Caplin, he proposed the L’il Abner strip to syndicates. It was Resnick’s

advice to reject King Features’ meddling in the strip’s premise, and accept an

offer from the smaller United Feature Syndicate.

It is not generally known that Elliot’s birth name was Elia Abner

Caplin; so Li’l Abner was an in-joke from its inception. Al would refer

to Eliot – never without his trademark wheezy laugh – as “that lovable idiot

Elliot,” but affectionately. The pair had supreme admiration for each other. (Jerry

became a Capp, legally.)

As I said, I knew Al Capp during the period when he multi-tasked,

diverting attention from his strip to politics. Claiming he never changed his

famously liberal stances that infused Abner for years, it was the

leftward stampede in American politics that made him seem like a conservative.

Whatever. Almost overnight, as he lampooned hippies and limousine liberals in his strip, he found himself a favorite of William F Buckley; a guest on Firing Line and late-night talk shows; a newspaper columnist; and a speaker on the college circuit. Like Ann Coulter and Ben Shapiro of our day, he was picketed and the object of protests. Allegations that he propositioned “co-eds,” as female students were then called, severely damaged his celebrity.

The recent issue of Hogan’s Alley has a first-person

account of Capp’s lecherous advances (“amorous” is finally an inappropriate

term in these cases); and there were other similar claims, most famously by

Goldie Hawn from days before her own celebrity. Capp’s celebrity, but more

importantly his credibility, was damaged.

The article has a sidebar reproducing a column by Jack Anderson, a

prominent political writer of the day, about Capp’s peccadillo described by the

writer. Another serendipitous connection (a "Crowded life,"

after all). I was Anderson’s editor for a while, believe it or not. Personal

and political animosity fueled many of his “scoops.” His former boss, then

partner, on the “Washington Merry-Go-Round” column was Drew Pearson, who observed,

and skewered, everything from his far-left perch.

Capp mercilessly lambasted Pearson (for many years a fellow

liberal) in Li’l Abner. One

time I asked Pearson about the bad feelings, and he would not confirm that when

Pearson himself created (and thereafter "edited," but credited as a

writer) the newspaper-reporter strip Hap Hooper for Capp's own

syndicate, United, its hero was spoken of internally as a serious-world Li'l

Abner type. A hillbilly who stumbled into situations. Capp was livid, even

after the premise was somewhat revised – and the incident became one on a list

of grievances Capp held against his syndicate for years.

It would not have been above, or beneath, Jack Anderson to be

joyful in “exposing” the claims against Capp for his own “exposing” events. By

the way, one of Anderson’s legmen in those days was Brit Hume, before ABC News’

White House beat, and as Fox News Channel’s Senior Analyst. Times have

changed.

[Speaking of exposing, I have received many inquiries about me and

Hogan’s Alley, prompted by my essays for Yesterday’s Papers and

the announcement of Nemo Magazine’s imminent revival. Formally, I have

not left Hogan’s Alley and in fact am on track to deliver an article for

publication. I founded, or co-founded, the magazine, named it, invited the Art

Director David Folkman to join the team; and I retain an equal-ownership

position with Editor Tom Heintjes. Nevertheless this latest issue sees my name

dropped from every category in the staff boxes. When Dorothy McGreal invited me

to write for her excellent World of Comic Art, she specified that I

should feel free to write elsewhere. After writing several articles for Cartoonist

PROfiles, Editor Jud Hurd kindly blessed my writing elsewhere, and said his

door was always open. The foregoing might answer the questions of some people,

even if not mine.]

Back to Capp: Previous to the assault allegations, he had been

discussed as a candidate against Massachusetts Senator Edward Kennedy… but all

that collapsed.

So did his health and his leg. As a boy in New Haven, Al Capp was

run over by a street car, and forever limped noticeably and bravely, and a bit

awkwardly, on a wooden prosthesis for the rest of his life. In rare appearances

toward the end, even at cartoonists’ events, he was “handled” by Eliot, helping

Al walk and deflecting conversations, even from well-wishers.

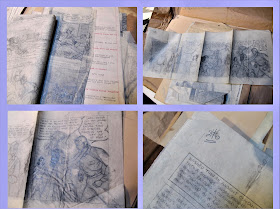

Back in cartooning’s turf, I acquired items from his crowded

studio (organizational chaos must have run in the family: Elliot’s office in

Manhattan was smaller than most people’s utility closets – but he never could

lay his hands on proof sheets of his collaborations with, say, Lou Fine, Ken

Bald, and Neal Adams – he knew how to pick ‘em!) and I conducted Al Capp’s last

interview.

Some day, here, I will tell more of my interview, conducted after

he very publicly retired Li’l Abner (“It simply is time for a fresh, new

talent, to take my space”). Al was miserable. He had difficultly reaching the

living room and settling in an easy chair; he complained of his emphysema – but

chain-smoked (“It’s simple; I can give these up or stop breathing,” between

drags). He complained, I tentatively recall, of diabetes. A joy for him, during

that afternoon, was the presence of his granddaughter, a reporter for the Newark

(NJ) Star-Ledger. Tragically the following week she was killed by a

car when she crossed a street.

He shared a lot with me that day. As I said, we’ll dive deeper in A

Crowded Life, but I remember that he disputed the length of time Frank

Frazetta assisted on Abner. And the wonderful answer to my question

about the greatest humorists: he said the great American comic writers were all

named Sol and Nat, representative of the anonymous radio-show staffers of the

1930s. He drew a terrific self-caricature for me that afternoon in Cambridge,

looking as jolly as, sadly, he was not.

Al and Elliot liked the interview I conducted (published first in Cartoonist

PROfiles) and wanted me to ghost-write Al Capp’s autobiography. So did Don

Hudder, a friend who was Editor of Simon and Schuster. Tony Gardner, Al’s

nephew and then agent, got involved, and eventually my modest fee was too high,

and the book was published, “by” Al Capp. It was, frankly, a pastiche of my

annotated interview in many places; and four-fifths strip reprints… from the

recent past. The Best of Li’l Abner, which it was not; and scarcely

claiming to be an autobiography. I still have Hudder’s letter apologizing for

the slight and affirming that I could have made a good treatment even better.

I the meantime, it was, of course, a privilege to know and work

with Al Capp – in two spheres of Crowded Lives, his and mine.

👀

36