Thursday, September 26, 2019

Sunday, September 22, 2019

A Crowded Life in Comics –

Down the Bunny Trail

Rick Marschall

I have

just returned from the 14th annual Symposium of the Theodore

Roosevelt Center at Dickinson State University. I recently was named their Cartoon

Archivist, as noted here, and indeed the keynote was a “Cartoon-Off,” with the

honorable Clay Jenkinson and myself showing 15 cartoons each, commenting, and

inviting the registrants’ votes.

Among

many things to which my “mind” raced back was not Roosevelt specifically, but

peripherally:

When I

was very young I already had twin obsessions – more than a couple, really – but

two were Roosevelt and vintage cartoons. My mother’s mother was born in New

York City of German parentage. She moved from Manhattan when young and quickly

acquired and never lost a Brooklyn accent. “Berl the water” and “Don’t get boined,”

were such footprints of speech.

Perhaps

her ears were affected, too; or maybe my famously quiet voice, but one day in

the kitchen I wanted to ask if she ever laid eyes on Theodore Roosevelt in her

youth. An “excuse me” and a “what?” and

“speak up” had me repeating “Theodore”… until she thought I was asking if she

attended the theater as a girl.

An

unconscious shift to my second interest. Her face lit up, and she recalled

being taken to a Broadway musical as a girl. It was one of several musical

comedies staged around the pioneer comic-supplement character Foxy Grandpa. She

didn’t remember much about the plot or the songs… but she remembered that there

were moments so funny that a fat man sitting on the aisle laughed and laughed.

“His face

turned so red when he laughed that I thought he was going to pop!” she told me.

So that was tattooed on my memory, too, and through years since I cannot think

of Foxy Grandpa and his two grandsons without thinking of little Augusta Vagt

watching that man almost laugh himself to death.

Foxy

Grandpa commenced

in 1900 in the color pages of the Sunday New York Herald. The artist was

Carl Emil Schultze, who had signed his cartoons in Life magazine with

his surname, but his newspaper work as “Bunny,” often beside a furry

mascot. His other features for the Sunday funnies were random gags or short

strips under the title Vaudevilles, and were collected in a book of that

name.

An

immediate hit was Foxy Grandpa. Its premise was simple – indeed, a

one-gag premise. Oddly enough, the early strips virtually all were variations

on a single joke. Happy Hooligan was a well-meaning tramp whose kindly efforts

backfired. Hans and Fritz would conspire, execute a prank, and be punished. Little

Jimmy was distracted from every errand, with comic results. Buster Brown’s

pranks went awry on their own. Maud the Mule kicked people – usually her owner,

Si – into the next county to assert her dominance. Alphonse and Gaston’s politesse

inevitably resulted in chaos, not order.

… and so

on. In all, a remarkable but ironic foundation for commercial successes and a

viable and pliable art form. Yet such was the early days of the comics. Foxy

Grandpa’s formula was, simply, the mirror-image of the Katzenjammer Kids.

The grandsons plotted a trick on the old boy, who predictably outsmarted them

in the ultimate panel. It is amazing that for almost 20 years the boys were

surprised each week. And each week.

And in

various formats, appearances, books, and Broadway musicals. As far as I have

seen, or remember (having the complete run in the Herald and Hearst’s American

to which he moved amidst much fanfare soon afterward; and ultimately to

Munsey’s Sun) neither Grandpa nor the boys had Christian nor surnames.

Neither “Little Brother” who eventually joined the cast. No intermediate

generation of parents were ever seen, beginning tradition that a homonymic

namesake, Charles, continued. (On stage, Grandpa had a name: Goodelby Goodman;

and the boys were Chub and Bunt.)

I will

share here memorabilia including buttons and songsheets generated by the stage

sensations. Not pages nor reprint-book covers here; maybe later.

“Bunny”

had a sad ending to his life and erstwhile successful career. He died in

poverty in New York City’s West side in 1939, filling his last years with

occasional pages for early comic books, a couple of children’s books, and

drawing sketches of Foxy Grandpa for neighborhood businesses and kids.

53

Wednesday, September 18, 2019

Saturday, September 14, 2019

Western Illustrations of Arthur H. Lindberg

Arthur

Harold Lindberg

1895 Born in Worcester, Massachusetts, the

son of an immigrant Swedish Metal Worker.

1909 At 14 years old, worked his first job

at the Goddard works of the Wickwire-Spencer Company, Worcester. (Worked 54

hours a week at 10 cents an hour)

1915

Graduated from high school at the

age of 20, took art classes at the Worcester Art Museum School, then studied at

the Pratt Institute, Brooklyn.

1917 During his senior year at Pratt,

enlisted in the US Air Force and served 14 months in France as a Sergeant-Major

during World War I.

1919-22 After the war, returned to Worcester,

worked at Wickwire-Spencer and resumed evening art classes at the Worcester

Museum School, and then moved to New York City.

1922-30 Studied nights at the Grand Central School

of Art, and the Art Students League of NY, where he was awarded a life

membership for his superior work.

Studied under Harvey Dunn, Dean Cornwell, Frank Vincent Dummond and

George Bridgeman. Worked as a commercial

artist. Became friends with Girard Delano

and a student of Walter Beck, who advised him in making his own pastels.

1927 Married Esther Perry Barlow, who

learned to paint under his tutelage and became and accomplished watercolorist

and was also an award winning quilter.

They moved to Long Island, NY, the new headquarters of Wickwire-Spencer.

1928-29 Illustrated Western Magazines – now

referred to as pulps

1931 Daughter, Perryann born

1933-37 instructor & Registrar at Nassau

Institute of Art

1937-38 Did illustrations for Gulf Oil Company weekly

cartoon strip about the Mayan Indians.

1939 Received BFA at the Pratt institute

1941 Received BE in Art at the Pratt

Institute, and moved to Buffalo, NY.

Took Art Instructors position at Kenmore Senior High School.

1942-43 Worked steel production in the summer in

Western NY factories doing war production.

1944-45 Taught private art classes, did illuminated

scrolls, started doing art restoration of paintings.

1946 Summer study, received MA at Columbia

University

1946-48 Obtained permission from the City of

Buffalo to enter industrial site (previously restricted due to defense work)

and executed a series of fifty paintings.

He found beauty and color even in the blast furnaces of Bethlehem Steel.

1947 One man show at Carl Bredemier

Gallery, Buffalo, “Our Industrial Waterfront”.

Received Frontiersman Award from Buffalo Business Magazine for the time

and effort he had given to the presentation of Buffalo Industrial scenes in oil

paintings.

During the mind 1940’s was

voted into the Buffalo Society of Artists by its members. Exhibited in the society’s membership shows

and served as its president in 1954 and 1955.

Arthur H. Lindberg

devoted his retirement years to art, private art classes, illuminated scrolls, cleaning

and restoration of paintings, commissioned portraits and Fall painting trips to

New England. Increasingly frustrated and

disillusioned by emphasis on and the support of abstract art in the Buffalo Art

Community, he refused to exhibit his work for fear of being misunderstood and

rejected for continuing as a realist in such pro-abstract surroundings.

He was commissioned to do

illuminated scrolls for many groups and people in the Buffalo area. He was especially proud of the scroll which

was presented in 1955 to Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth of England.

Art was active with the

Buffalo Society of Artists and was president for a couple of years. He sketched with Art Kowalski, Bill Ludecke

and Walter Prochoniak.

Art painted in oil,

watercolors and pastel. He loved to

include water in his paintings and was drawn to the shipyards in New England,

as well as the waterfront in Buffalo.

Another series of his paintings represented the area around Stowe, VT

with its’ brilliant fall color.

1953 Did independent study in Sweden and

Denmark, and was included in Who’s Who of American Artists.

1977 Died in Kenmore, NY.

1980 Retrospective show at AAO Gallery,

Buffalo, NY.

1982 One man show, “Beauty in Buffalo

Industry”, held at the International Institute, Buffalo.

1984 Included in exhibit “Buffalo

Waterfront”, at the Charles Burchfield Center, State University College at

buffalo, Buffalo, NY.

1987 Included in exhibit and catalogue “The

Wayward Muse: A Historical Survey of Paintings in Buffalo”, The Albright-Knox

Art Gallery, Buffalo, NY.

1987-88 One man show of industrial paintings of

Buffalo’s waterfront, Linda Hyman Gallery, NY City, NY.

1988 Retrospective exhibit of drawings,

watercolors, pastels, lithographs and oil from 1916 to the late 1960’s, at Art

Dialogue Gallery, Buffalo, New York.

2009 Six of Arthur H. Lindberg’s pieces are

in the Burchfield Penney Collection, Burchfield Penney Art Center, Buffalo, NY

and one piece is in the permanent collection of the Albright-Knox Art Gallery,

Buffalo, NY.

[3]

[4]

[5]

[6]

[7]

[8]

[9]

[10]

[11]

[12]

[13]

[14]

[15]

[16]

[17]

[18]

[19]

[20]

[21]

[22]

[23]

[24] Mimi and Papa

[25]

[26] Shields & Co. Mural

[27] Courtyard Art Show

[28] Richard Nixon Scroll

[29] Arthur H. Lindberg Article Pg. 1

[30] Restoration Before and After

Previous Post:

Cartoonist Arthur H. Lindberg (“Lyndell”) and Gulf Funny Weekly

Arthur H. Lindberg’s Gulf Funny Weekly comics and artwork

have been donated to Ohio State University

Special thanks to Pam H.

⚪

Sunday, September 8, 2019

A Crowded Life in Comics –

A Mock Feud In the Pages of Puck.

by Rick Marschall.

Show

business, sports, and politics are replete with stories of feuds. I say

“stories of feuds” because many of them are manufactured for the public’s attention

if not enjoyment. There are, of course, bitter and long-running rivalries that

have poisoned the wells of comity, certainly within families. In other spheres

of life, self-interest or self-preservation usually triumph.

The old

Jack Benny-Fred Allen “feud” attracted listeners and gossip for years, but the

radio comedians were friends. Likewise W C Fields and Charlie McCarthy; but it

is difficult to stay angry at a piece of wood for too long.

And we

remember Ralph Kramden’s threat (in The Honeymooners) to a momentary

opponent: “When I see you walking down the street, move to the other side!” And

Norton’s response: “When you walk down the street, there ain’t no

other side!” Somehow the perfect squelch, the mot juste, resonates more

than love lines do.

In the

supposedly staid Victorian Era, there was an example of “inside jokes,”

sarcasm, camaraderie, and a mock feud that is funny today. I will share brief

details here.

Puck Magazine commenced as an

English-language weekly in 1877, a few months after founder Joseph Keppler

launched the German-language edition. It became America’s first successful

humor magazine, although dozens had existed, with varied acceptance, since the

1840s. Puck featured lithographic color cartoons – an attractive wrinkle

– on its front, back, and middle-spread pages; usually political themes. The

bulk of the cartoon work, including black and white social cartoons on interior

pages, soon fell to Frederick Burr Opper.

Opper

(1857-1937) was a workhorse of incredible talent and native humor who followed

Keppler from Leslie’s Weekly, and known to comics fans today as the

creator of many seminal comic strips around the turn of the century into the

1930s (Happy Hooligan, etc).

Almost

from the beginning, the fecund H C Bunner was the mainstay of Puck’s

editorial columns. He wrote the paper’s editorials and provided ideas to

cartoonists; he signed poems and funny stories, and contributed many anonymous

works; he recruited and trained a host of talented humorists for the succeeding

generation. Unjustly neglected and forgotten today, Bunner was a master of the

short story in the manner of Frank Stockton (another forgotten genius). The

American short story of the day was a wonderful genre, now scarcely

commemorated by limp rose petals tossed toward O Henry and Saki, but whose

ranks were populated by clever writers like Bunner.

Many of

Bunner’s books were in fact collected short stories originally written for Puck,

and illustrated by Opper (and, chiefly, by C J Taylor).

In 1884,

amidst the fury of the nation’s most contentious Presidential election,

Cleveland vs Blaine, Opper and Bunner conducted a sideshow for readers through

a mock feud. The national election was in fact mightily influenced by the

“Tattooed Man” cartoons in Puck, depicting the Republican Blaine

stripped to his skin, on which was festooned his many political scandals and

sins.

The

editorial fusillades that season mostly were Bunner’s, but the cartoons were

Keppler’s, Opper’s, and Bernhard Gillam’s. Opper, relatively young, drew

cartoons that sometimes were less than polished. In a letters column – “Answers

For the Anxious,” probably manufactured

within the offices – notice was taken of an awkward cartoon by Opper of

politicians attempting to stop a water wheel at a mill.

Puck’s reply (surely written by

Bunner) thanked the reader but also criticized his spelling and grammar. Opper

the cartoonist, however, was defended with faint praise.

In the

next issue, “the artist” responded, angrier at the Editorial Office’s weak endorsement

than of the critical reader. And the following week, the Editor shot back in

mock dudgeon, stating that it was barely worth the time to wallow in matters concerning

mere mortals – cartoonists. In subsequent weeks Opper fired his shots through

cartoons more than words.

It was

grand fun. Claiming the dignity of an Oxford Union debate, it spilled itself

before readers like a barroom brawl. As I say, grand fun – no reader would have

thought otherwise. But, again, in the stuffy Victorian era, such entre-nous

peeks behind the curtain of kidding and elbow-poking sarcasm was rare. Still

fun.

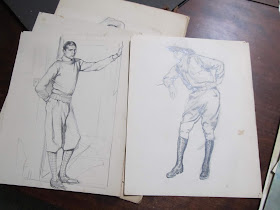

Some day,

somewhere, I will reprint all the exchanges, insults, and mock threats. Here,

however, Opper’s drawing of the theatrical “truce.” Naturally, he cannot keep himself

from depicting H C Bunner (with fair accuracy, trademark cigarette and pince-nez

specs) as a coiled viper; and himself as

an artiste crowned with a laurel wreath.

Original art

from my collection, first the half-finished pencil sketch; and the “finish” as

it appeared in the happy pages of Puck through the Summer and Fall of

1884.

RM 52