Chronicler of Many Adventurous Decades Rick Marschall  |

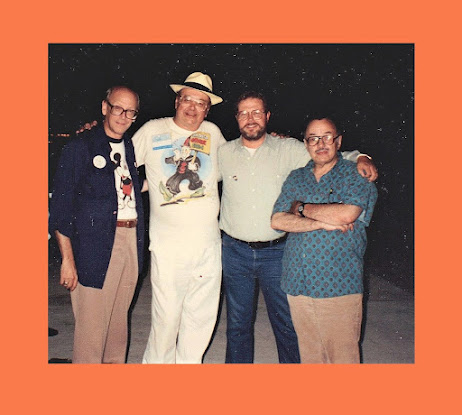

Birds Of a Feather? Rick Marschall and Ron Goulart on the right; R C Harvey and Shel Dorf, left. |

Ron Goulart died on the morning of January 14th, 2022. It was the day after his birthday: an irony wrapped in a riddle strangled by a conundrum. Actually the date was merely a coincidence. No, it was an irrelevant fact.

I am struggling with a way to begin this, fooling myself that I can “open” with a type of grabber that he did in one of his, oh, 200+ novels.

Tougher than a “lede” will be how to close this remembrance, because with Ron there was always a story to be continued, or a sequel, or a next book; or a conversation to be finished next time. A “hook,” maybe; a cliffhanger. Or a happy ending.

But, no. Ron Goulart died on the morning of January 14th, 2002. “The End.”

But only the end of those great long and rambling phone calls. Never with no point to them, but rather dozens of points. Funny. Trains-of-thought. Questions. Answers. Frequently with grumbles and complaints. Gossip. Memories from, say, something we he and I did 45 years ago. Even a loose thread from a chat we both remembered from 45 years earlier.

But Ron’s “passing” was not the end of his legacy. Three hundred books (we must also remember the numerous histories and anthologies); bottomless pits of clips and files and letters – the collection that not only filled his Connecticut homes (making mazes of living-room floors, between stacks) or with his friends, sometimes vaguely remembered, across the continent, who held his “stuff.” The stuff ranged from mail-in premiums to personal sketches he received from an array of legendary figures.

Many aspects of Ron Goulart will live forever. Not the least in the fond memories and now broken hearts of many friends and uncountable strangers he inspired.

I first met Ron at some Seuling Con or other in New York City, those early conventions in small, seedy hotels, before the days when Phil Seuling expanded into large, seedy hotels. It was the 1960s, and I was a young fan of strips, attending with my usual sloppily tied portfolio of originals. Ron routinely showed up with a retinue of Connecticut friends – cartoonists who had peripheral interest in vintage comics and vintage artists and vintage tales. Ron and I shared knowledge of ancient lore, even from before our times. Affinity. His friends – Bob Weber, Gill Fox, Orlando Busino – became my friends too.

[Having invoked “irony,” I will note here that only three days before Ron died, our old and beloved mutual friend Orlando Busino died. My next column will recall this great cartoonist and great man.]

(l-r) Gene Hazleton; Rick Marschall; Sheldon Moldoff; Ron Goulart; Dick Sprang; Vin Sullivan. (Photo by John Province)

A few years later I moved into the midst of Cartooning Country, Fairfield County, Connecticut. I was political cartoonist on The Connecticut Herald, and lived in Westport, then Weston. Most important, perhaps, was the full-bloom friendship with Ron Goulart (and Bob and Gill and Orlando).

A rather wider circle, in those halcyon days, consisted of cartoonists like Dik Browne, Dick Hodgins, Jerry Dumas, John Cullen Murphy, Jack Tippit, Frank Johnson, Mort Walker, Stan Drake, and Len Starr… at parties, BBQs, Long Island Sound cruises, golf outings. But a circle within a circle comprised the merry men I described around Ron – Weber, Fox, and Busino. With Jerry Marcus and Joe Farris and Jack Berrill and a couple other guys, it was a virtual fraternity.

Ron, in fact, described our group as a Movable Frat Party, no offense to Hemingway. At least twice a week we gathered for early lunches, sometimes in Westport but usually in Bethel or Ridgefield. More often than not we straggled in to a restaurant… exchanged news… looked at the menus… at which time Jerry Marcus would complain about something or other, and we then discussed where else to meet in 10 minutes. Lunch was eaten leisurely and we talked and laughed, laughed and talked. Sometimes we adjourned to my house where I would do a show-and-tell with vintage art or Sunday funnies.

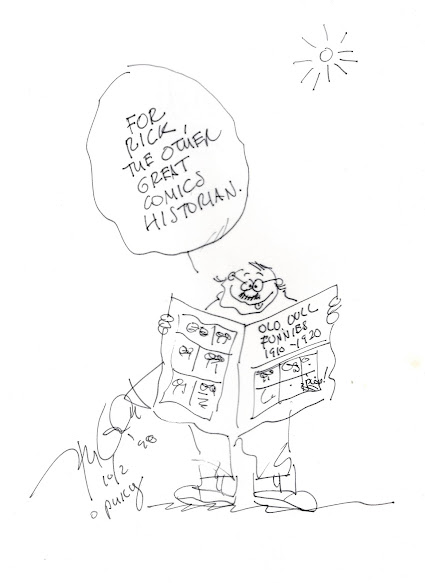

Ron and I saved a lot of money through the years by reliably presenting our latest books to each other, always with inscriptions and drawings.

Invariably, Ron was the focus of impromptu trivia challenges – “Who Was What,” for instance (he was a fount of knowledge about the sexual leanings of Hollywood’s bit players) or great stories about scores of cartoonists and writers he met as a fan in his youth.

As evening approached, we all scurried home in time for dinner. Our wives suspected that we goofed off during these days, but we knew the truth – we goofed off on these days. Occasionally, however, we straightened up. That is, we met for midnight snacks at a local diner instead.

Ron was always at the center of such get-togethers. He was as funny as the cartoonists, and usually more interesting, which everyone acknowledged. He always had news about his latest projects, or frustrated projects; and he added us, variously, as characters in his books. Oddly, if not inappropriately, not always as heroes or innocent bystanders.

Ron and I traded a lot of stories and a lot of cartoon collectibles. I brought Bill Blackbeard up to meet him, and once we traveled down to New Jersey to meet Boody Rogers (joined by a gosh-wow Craig Yoe). I interviewed Ron for my paper (“The Master of Ghoul-Art” was my title; horror fiction was one genre he seldom visited, but the pun was irresistible to me). When I was a comics editor at three newspaper syndicates I tried to get this maestro of so many fields to script a comic strip, but only (after me) did he collaborate on one – Star Hawks, with the local Gil Kane). Leonard Starr invited us both to do stories for Thunder Cats.

After I left Connecticut we kept in close touch. We bummed around Comicon together many times. We both contributed to Toutain’s Spanish part-series History of the Comics. When was editor at Marvel, I gave him writing assignments for the black and white magazines. When I launched NEMO magazine, about strip history, I commissioned Ron – of course! – for the first, and subsequent, issues.

When I moved from Connecticut, the “Movable Fraternity” had a farewell BBQ, everyone doing a drawing for a presentation binder. This was from Ron Goulart and wife Fran, evoking – as many of his drawings and notes did, a moldy strip character. Here, Slim Jim.

I am bragging, obviously, about having known Ron Goulart. I was proud to have known him and to have worked with him. But peripherally, for any uninitiated readers, I have shed light here on his many activities in many areas.

We shared tips and leads as freelancers in the same fields. Slow-pays and no-pays are banes of our “existence,” such as it is. He shared backstage-stories about ghosting the TEK Lab series “by” William Shatner. We had similar reactions to R C Harvey virtually accusing us of character assassination for writing that Milt Caniff occasionally relied on other artists like Bud Sickles. Ron would have written a regular for the imminent revival of NEMO magazine.

Many contemporary fans and scholars of vintage strips learned from Ron’s many books and anthologies. Many fans of science fiction, mystery, and licensed-character novels have enjoyed Ron’s work… even without knowing it. Many of his books were ghost-written; and his list of assumed names was as lengthy and colorful as pioneer recording artists or clever confidence-men. (Did you really think Lee Falk wrote those Phantom novels, too?)

In fact, I was a fan of Ron Goulart before I knew there was much to read in the world beyond cereal boxes at the breakfast table. As a kid I hounded my mother to buy Chex cereal. She wondered why I eagerly risked the challenges to my regularity – but it was to read the Fake News called “The Chex-Press” on those cereal boxes. Hilarious! Ron Goulart wrote them for the ad agency, the early-and-often work of the most prolific friend (or stranger) I knew, Ron Goulart.

It is not often that a person can dominate fields of which he is also a pre-eminent, honest-broker historian. His personality – I mean his compelling arsenal of virtues – was more than humor and sarcasm, cultural acuity and cynicism. He occasionally was philosophical and introspective, too. Not particularly religious, he taught me, by example, the meaning of that Christian virtue, unconditional love.

“To be continued”? Actually, yes. Until printing presses and used-book stores disappear, Ron Goulart will indeed always be with us.