Another Survivor. Another Tale.

by Rick Marschall

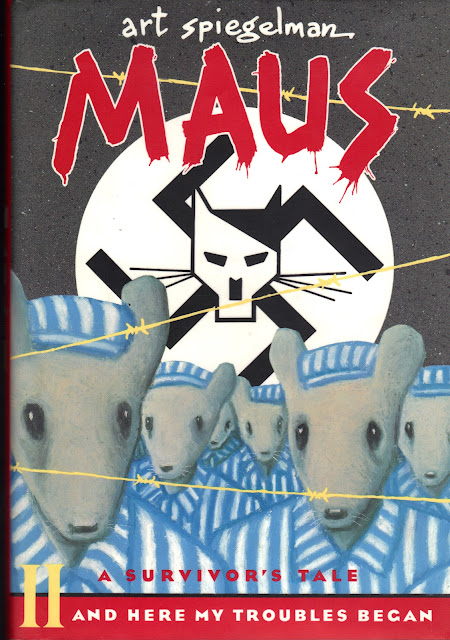

Art Spiegelman is in the news, prominently again; and from which the modest but talented cartoonist never should be far, because he always has things to say. His magnum opus, the Pulitzer Prize winning graphic novel, Maus, has returned to the top of best-seller lists.

Maus in one of its levels is a personal memoir; seen through his eyes, seeing history through his father’s eyes. But writ, or drawn, large, it fixes the world’s eyes on concentration camps and the Holocaust. Hannah Arendt identified the banality of evil, but Art’s contribution to Holocaust literature is perhaps the depiction of how unique horrors simultaneously could inhabit, and corrode, the most private places of individual emotions.

As Hall of Fame baseball players all began their careers on sandlots and in the minor leagues, Art paid his dues as a cartoonist. Yet he never did minor league caliber work as a cartoonist, and indeed was a figure in many significant places, and among other cartoonists who also achieved prominence. He was part of the Underground movement whose West Coast names like R. Crumb defined a generation. Themes of social and political protest paralleled the graphic experimentation that arose from those studios in San Francisco and Seattle.

At another extreme, perhaps, was the corporate work Art oversaw when back on the East Coast, with Topps, the company that produced bubble gum and trading cards. Hardly a gray-flannel suit executive, Art worked for the legendary Woody Gelman, and virtually institutionalized (and sanitized) the Undergrounds – or, perhaps, MAD Magazine – overseeing products like the Garbage Pail Kids.

Contributions to various Undergrounds, and contact with the movement’s artists, led to Art and his wife Françoise Mouly to establish a slick, stylish, graphic magazine with mature sensibilities, RAW. Its immediate impact and success can be seen as a latter-day counterpart of The Masses, which in 1911 summarized and succeeded many smaller protest and avant-garde publications. Thematic preoccupations were many, in each magazine, but graphic excellence was the irreducible standard.

The rest, similarly condensed, is history. Maus, before its serial chapters were collected as books, found its home in RAW.

I first met Art not in New York or the United States, but at a European comics festival as was my experience with many other cartoonists. I had been a guest at the Lucca Salon of Comics, Illustration, and Animation since the 1970s, as member of juries, as an exhibitor, or as a participant in round tables. Today the event in the quaint Tuscan city largely has been given over to games and computer animation, but in those days was a major intellectual event. Historical monographs, debates, and awards were major components.

In 1982 Art was one of the American guests, and he was presented with the Yellow Kid award.

We shared some panels and round tables, as well as fraternization at Lucca’s restaurants and bars late into the nights. Truthfully, there was as much beneficial interplay, and even business deals, in the festival’s after-hours as in the scheduled events. Cartoonists and historians from all over the world communed; multi-lingual friends were never far away; and if language ever became a challenge, Hugo Pratt would pick up a guitar and sing. Or cartoonists would sketch. Halcyon days.

I recall the last day of Lucca that year. Some guests gathered in front of the Hotel Universo, on the plaza of the Teatro Giglio (the opera house, Lee Falk reminded us, where Puccini began his career), waiting for rides to the train station or the airport in nearby Pisa.

We went on to share professional and personal friendship and interplay, even without the smoky ambiance of Lucca’s hotel lounges. Art and his wife Françoise – now The New Yorker’s art editor – visited my wife Nancy and me at our home in Connecticut, and I was a guest in their loft in lower Manhattan. Art occasionally borrowed books and vintage magazines from my collection.

When RAW and other activities increasingly occupied Art’s time, he recommended me to succeed him at the School of Visual Arts, where he had been teaching a course on “Language and Structure of the Comics.” I wound up at SVA for years, teaching that class and additional courses of my suggestion. When I had to be away myself, among my substitutes were Donald Phelps. – introduced to me by Art, for which I was very grateful – Peter Kuper and others. Some of those cartoonists, and many of my students, are friends to this day.

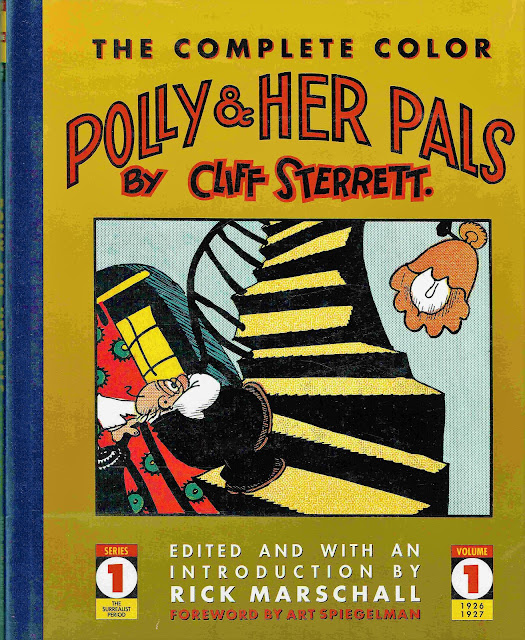

As Maus was serialized in RAW, I sometimes saw its work in progress, and I remember one half-inked page of whose construction Art was especially proud. The architectonic possibilities in comics was among Art’s intuitions, and when I published a reprint volume of Cliff Sterrett’s 1920s surrealistic color Sunday pages, I invited Art to write the foreword. It was a uniquely (and typically) perceptive essay limning the affinities between Sterrett’s art in Polly and Her Pals and Jazz Age music.

In 1991, I think it was, the Angoulême Comics Festival designated the “American Year,” and I was hired as the representative. Eventually more than 125 American cartoonists and publishers joined the jaunt to France, and we arranged a few days in Paris before and after the actual festival; a special BD-train was chartered for the trip south. Art was among the attendees; his interest in vintage French comics was separate from Françoise’s roots (I recall now that she once bought a run of L’Assiette au Beurre from me for Art’s birthday). RAW hosted the work of many French and Belgian cartoonists.

Our conversations were not always about comics and popular culture. A few years ago Art and I staked opposing views on the ideals of the German Romantic philosopher Gottfried Lessing. (Lessing’s disinclination, in his seminal work Laocoon, to apply similar critical standards to all art forms, was derived from Aristotle’s On Poetics. While this is the most persuasive of Aristotle’s essays to me, I am basically a Platonist.)

As noted above, Art Spiegelman is back in the news these days and Maus has returned to the top of best-seller lists. In news cycles swirling with various incidents of censored news, banned viewpoints, and a growing “cancel culture,” the Board of Education in a small Tennessee County voted to remove Maus from its curriculum for 8th-grade classes and seek “age-appropriate” works on the Holocaust..

The reaction of much of mainstream media has condemned the Board’s decision. They have evoked the Scopes Monkey Trial of the 1920s, and have raised spectres of Southern rednecks flexing their innate antisemitism: stereotypical illiterates perpetuating centuries-old bigotry. Art himself, in interviews, has cited the low reading-scores of students in rural McMinn County as he struggled with “bafflement” over the decision. He suggested the relative illiteracy of county residents as an explanation for school board members who might “possibly not be Nazis.”

There is a bit of nonsense about all this. The school board, whose minutes are available online, did not ban Maus from the county and its town libraries or bookstores, much less its school libraries. It removed the book from the curriculum of 8th-grade classes, citing its standing policies for pre-teens. The discussions manifested no antisemitism – quite the contrary – and there was agreement to substitute another book about the Holocaust in the curriculum.

Despite New Yorkers’ stereotypical beliefs about Tennesseans – and obviously different standards regarding language and images appropriate for, and recommended to, pre-teen students – there were no hints of bigotry in the board’s discussions. Even The New York Times and CBS in New York have reported on low literacy rates among New York City’s students (lower than those routinely reported for Tennessee students), so that factor seems not dispositive. New Yorkers might wish to impose their opinions about age-appropriate normatives to other communities, but they likely would object, and have chafed at the reverse – imposition of others’ cultural points of view on them.

Back in the news, as I say, Art Spiegelman has a chance to contribute to the important public discussion, and not be merely at its center. Interviewed on CNN (while eating breakfast and vaping; explaining that he was unaccustomed to answering questions at 8:30 in the morning) he delivered, according to one reviewer, “one of the greatest television interviews of all time.” The segment’s director, Ron Gilmer, subsequently wrote on Twitter, “In 49 years of directing TV news, I’ve never seen [anything like] this. He was amazing.”

If there was no antisemitism evinced in the school board’s deliberations, neither was there any prejudice against a “comic book” per se being in a school curriculum. In this case Art may feel justifiable pride for the role he has played in elevating the acceptance of graphic novels, their potential, and the the codification of their narrative structure, in America.

Much is made these days of “cancel culture” – in contemporary America, almost everything becomes a slogan or a brand – and that likely is because many cultural things are being canceled: books, shows, songs, websites, posts, communications, and thoughts. The curriculum change voted by the McMinn County School Board is, relatively speaking, very likely in the minority of targeted themes.

When the tumult and the shouting dies, as per Kipling’s phrase, at the moment in America the persecution of cultural traditions, conservative values, and longstanding worldviews is more virulent, and currently successful, than contrary efforts against progressive agendas and iconoclasm. It is the stuff of daily headlines, often hyperbolic, and not likely to fade while the antagonists seemingly enjoy the tumult and shouting.

I have been in the unique position (I mean unique among people I know, anyway) of having had close relations, shared projects, and even friendships, with people on the Left and the Right; even the Far Left and the Far Right. And unique that, unlike most people except aid workers and missionaries, my victimized friends have suffered from wildly disparate sources of persecution. Innocent tourists in Washington on January 6, some in jail after a year with no charges filed against them. I knew one of the cartoonists murdered in the “Charlie Hebdo” massacre. Another friend spent a year in solitary confinement in a European jail for publicly (in fact it was privately) sharing his own research and views of historical matters. And so on.

I mentioned America’s predilection for making brands or slogans of every phenomenon – categorizing, I suppose; the easier to explain… but also the easier to dismiss.

So, currently, has Maus become, maybe more than ever it has been, a subset or detail of the cultural wars. In some people’s fevered imaginations, a minor adjustment (not banning) in that small county’s pre-teen curriculum might be a harbinger of crematoria erected across the mid-South; but I don’t believe it. The fact that there are far greater – let me say, at least, more numerous – censorious acts in the news, against conservatives, reminds us to retain perspective. Literal banning of Huckleberry Finn and To Kill a Mockingbird are two examples of Political Correctness on steroids. Who, indeed, are the fascistic masters of our minds? Once putative, now looming.

It might not seem so now, but Art Spiegelman is rather a victim of this cultural maelstrom. He surely is not a commercial victim; but he can be properly satisfied, in spite of the winds he faces, to be an essential voice of education and palliative debate.

Yet speaking personally (which is all I can do), and returning to our common devotion to cartooning history and the art form of the comic strip, I fervently hope that Art’s great talent and many achievements (no less shared by the justly, much-awarded Françoise), his encouragement of others, his fidelity to graphic excellence, his body of work, will not be subsumed by such controversies. That is, not the somber leitmotif of Maus, but the 8th grade’s curriculum adjustment in Tennessee.

History and art are not mutually exclusive, of course; least

of all Spiegelman’s own history and his own art. I return to Gottfried Lessing,

who believed that words and ideas are extended in time, whereas

representational art and graphics are extended in space. Art Spiegelman, rarely

among his peers but with remarkable frequency has melded the two in in his own

work.