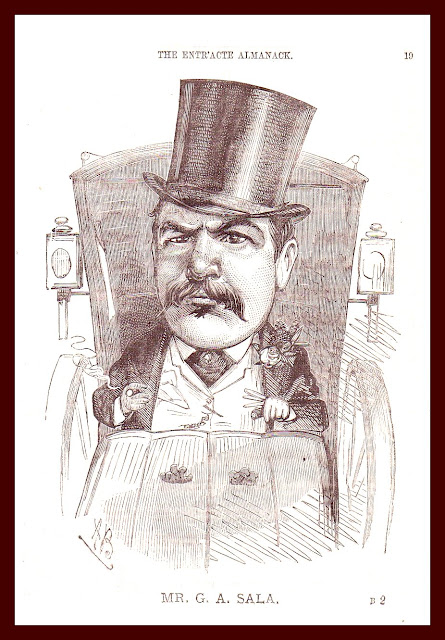

George Augustus Sala (1828-1895).

Caricature by Alfred Bryan (1852-1859)

by John Adcock

At 15, in London, George Augustus Sala began work as a clerk, draftsman, and scene painter, then became Editor of the weekly paper Chat. Mr. Frederick Marriot, the proprietor of Chat “had founded a truly original little weekly periodical with the lugubrious title of The Death Warrant. The office of this ominous periodical was in the Strand; and the window blinds were of black wire gauze, plentifully adorned with Death’s heads and cross-bones. The paper itself had a broad black border, and images of mortality were plentifully scattered through its columns; the letterpress being chiefly devoted to narratives of bygone murders, and descriptions of peculiarly atrocious tortures and punishments.” The paper was not a success.

He contributed a weekly article to Household Words for 5 years beginning in 1851. His first book was a collection of articles originally written for Words following a trip to Russia, entitled A Journey Due North. He was equally at home with society people, Bohemians and the disreputable ‘flash’ crowd. He described his early days as “Tom and Jerryism.”

He wrote thousands of articles and sketches for All The Year Round, Cornhill, The Illustrated Times and the Illustrated London News. In 1860 he wrote a novel, The Strange Adventures of Captain Dangerous, which appeared in Temple Bar. For twenty five years, starting in 1857, he wrote two articles a day for the Daily Telegraph. He was ridiculed repeatedly by the Saturday Review for his egotism and his “turgid” style of writing. In 1863 he was in Montreal and the U.S. to cover the Civil War. He traveled in Algiers, France, Italy, Spain, St. Petersburg and Australia, writing articles wherever he went. According to Tinsley, his book publisher, Sala was a heavy drinker, whose wife would accommodatingly go to stay with her parents when he was on a bender.

Sala published a novel under his own name, Quite Alone, in 1863. Sala wrote another article in 1863 called Unfortunate James Daley. James Daley was transported from Ireland to Botany Bay in 1788.Sala stumbled on a passage in an old book, An Account of the English Colony of New South Wales by Lieutenant Colonel Collins, which led him to believe James Daley was the discoverer of the gold-fields of Australia. “The settlement of Sydney Cove was for some time amused with the account of the existence and discovery of a gold mine; and the imposter had ingenuity enough to impose a fabricated tale on several of the people for truth.” Daley persuaded an officer to accompany him to his find, tried to escape and was caught and given one hundred lashes. He said he had fabricated the story and had worked up a specimen from a guinea and a brass buckle. Daley was hanged for housebreaking, sentenced by the aforementioned Collins. “He was whipped like a dog and hanged like a dog” and his “misfortunes are over and the kangaroo hops over his grave.” His fellow convicts believed he had really discovered gold and taken the secret to his grave.

Sala had a great interest in convict literature, his contributions to Chat were “a series of essays , called A Natural History Of Beggars; and a series of tragi-comical tales, supposed to have been related by convicts at the Antipodes, while reposing in their hammocks after sunset.” He entitled this The Australian Nights’ Entertainment. “Little did I think that I was destined six-and-thirty years afterwards to travel to Australia and to hear much stranger tales than I had woven... Marcus Clarke, who was for many years my junior, seems to have gone to the very same sources of information touching convict life that I resorted to in 1848.” “Now in 1848, I had been toiling through analogous convict literature in the reading-room of the library of the British Museum... Then I began to browse among the blue-books, and those touching Australia exercised so grim a fascination over me that I began to conceive of “The Australian Nights Entertainment.”

Vernon Lee (Violet Paget) described him as “a red bloated, bottle-nosed creature who poured out anecdotes in a stentorian voice.” Sala claimed his nose was the result of a bar brawl which split his nose in two. In British historian Ronald Pearsall’s book, The Worm In The Bud (1969), a pornographic work entitled The Mysteries of Verbena House; or, Miss Bellassis Birched For Thieving, is attributed to Sala. In 1894 he finished The Life and Adventures of George Augustus Sala, in two volumes, and died in 1895. In the Preface to Life he wrote of receiving an anonymous letter ‘in which the writer abused me violently for what he styled my “shameless and wearisome egotism.” “It is always I, I, I, I, I, I, with you,” wrote this courteous scribe, “and everybody is heartily sick of you, you, you, you!”

Sala said he had “an almost equally active propensity to gather up several editions of “The State Trials,” “The Newgate Calendar,” “The Malefactors’ Register,” “The Causes Celebres,” and any odd volumes of the “Old Bailey Sessions Papers” that I can come across, I cannot really account for. But everything has its final cause. The final cause of bread is to be eaten; of a so-called impregnable fortress, to be taken; of a burglar-proof safe, to be forced open by burglars. Perhaps the final cause of my collecting criminal literature will be that I shall be hanged.” He also collected Goya’s Caprichos, and Disasters of War, grim and hopeless works that have never been surpassed.

In the two volume collection After Breakfast; or, Pictures Done With A Quill (1864) is an article entitled “A Tour Of Bohemia.” “Court and fashion can no more boast of or bewail their Bohemianism, than law and the church and commerce; the severities of sectarianism, the rigidities of money-hunting, the asceticism of business, the preoccupations of statesmanship, the endless cogs and wheels and pendulums, and bolts and bars, with which mankind have fenced about the social clock to regulate and steady it, and cause it to keep exact time, and chime the hour with decent intonations- are all powerless to subdue Bohemia, which is forever playing tricks with the hands of the clock, meddling with its weights, tampering with its springs, causing it to run down and go wrong, but never to stop; so as to necessitate from time to time the calling in of some state clock-maker, who oftimes makes only a sorry bungling job in mending the machine.”

The article deals mainly with the Bohemians of the upper classes, the ne’erdowells and remittance men of the aristocracy. “Young Tom squanders the money, entertains fiddlers, buffoons, horse jockeys, prizefighters, bona robas, &c.; and is, in time, taken in execution, or under a commission de lunatico, or marries a hideous old woman for her money, but he never dreams of being of Bohemia – a Bohemian... There is scarcely a ship sails for Australia without a ruined spendthrift aboard, shipped off to the Antipodes by his friends to prevent him coming to worse; there is scarcely a public-house without some sodden Tom Rakewell, far gone in delirium tremens, who has had money and run through it all. You will not walk ten paces in the courtyard of a debtor’s prison without seeing the shawl dressing gown fluttering in the breeze, and the tasseled cap of incarcerated Tom, who has been in the Guards, or the Line, or in nothing particular, save the general debauchery line, and has sown his acceptances broadcast, and bought jewelry and double-barreled guns on credit, to pawn.”

It is little wonder that Sala and other one time penny-a-liners did not brag of their penny dreadful days, in his Life Sala describes his days on the staff of the Daily Telegraph; “There existed, not only among the Conservatives, who thought that the cheap daily press could only be the prelude of sedition and revolution, but also among a large number of journalists, and Liberal journalists too, of high standing, the most violent of prejudices against the new order of journals which were usually contemptuously called the “penny papers.” Dickens himself, a Liberal of the Liberals, expressed but very halfhearted approval of the agitation for the abolition of the paper duty; and it is a most amusing fact that members of the staffs of such expensive journals as the Times, the Morning Chronicle, the Morning Post, the Morning Herald, and the Morning Advertiser, looked down with aversion and disdain on the contributors to the “penny press.” In those days there was a kind of informal cenacle, or club, of newspapermen held every night in an upper room of a tavern of the “Red Lion,” in the Strand. I have seen William Howard Russell there. I was first taken to this select gathering by my friend already mentioned, Henry Rumsey Forster, of the Morning Post; but the veteran journalists, especially those connected with the Herald and the Post, vehemently protested against the young man known to be connected with a penny paper, being allowed to join them.

The drollest episode of all in connection with the horror felt, or assumed to be felt, by the established newspapermen at the audacity of the penny journalist presuming to associate with them, occurred on the occasion of that festival of the Literary Fund, of which I have already made mention.”

After the speeches reporters would retire to a private room for cigars, brandy and soda. “When at the dinner to which I allude an adjournment was made to the private room, my confreres – at least , I thought them my brethren, but they were not of the same mind – flatly refused to admit me to their company. But the landlord, wise in his generation, and knowing that the Daily Telegraph was rapidly progressing in power and popularity, and that a notice in its columns would do him no harm put his foot down, and pithily informed the gentlemen of the Press that they might go away if they liked, but that the private room was his, that he had invited me – I think he called me Mr. Saunders – to smoke a cigarette there, and that there I should remain. Which I quietly did.”

George Augustus Sala is not considered one of the great Victorian writers but he was certainly one of the great journalists of the age; he was a master of the literary anecdote and he wrote so many articles, he is probably more important to biographers and historians than Dickens or Thackeray, in our time. With his ability to mingle with the high and the low, and a sharp memory, the result of his childhood blindness, he left a ton of interesting material, much of it still hidden away in the many periodicals to which he lent his sharp and witty pen.

❦

.png)