♠♠ by Robert J. Kirkpatrick

C.A. Ransom was once well-known as a collector of and dealer in penny dreadfuls, boys’ story papers and boys’ books. He ran a bookshop in London for many years, and he also sold items by mail order, advertising in boys’ papers. In the late 1920s he was also a publisher of cheap comics and paperbacks. At the same time, using the name Charles Dare, he was a major theatrical impresario, running a succession of minstrel troupes, owning theatres, and performing himself as a comedian and singer. The mystery is who exactly was C.A. Ransom, and how did he combine these two totally different careers? Indeed, was he one person or two?

Amongst the evidence that Ransom and Dare were the same person is Ransom’s Probate record, which gives the names “RANSOM Charles Albert or DARE Charles.” A brief obituary in The Era in June 1939 referred to “Charles Albert Ransom, well known as a provincial theatre manager under the name of Charles Dare.” An item in The Examiner on 8 May 1920, referring to Charles Dare’s activities running minstrel and pierrot shows on the Isle of Man, noted that his real name was Charles Albert Ransom. Alternatively, Bill Lofts and Derek Adley wrote (in an issue of The Association of Comic Enthusiasts Newsletter – date not known) that it was believed he was “born in London in 1858, his real name was Charles Dare, though for reasons unknown he later changed it to the familiar Charles Albert Ransom.” And Alan Clarke, in his Dictionary of British Comic Artists, Writers and Editors (1998), has an entry for Charles Dare as a “publisher of cheap comics under the name of C.A. Ransom.”

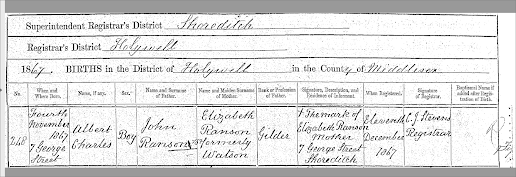

To begin with, there is no relevant birth record for either Charles Dare or Charles Albert Ransom. Census records suggest that Ransom was born in Shoreditch in 1868 or 1869. In fact, he was born on 4 November 1867, at 7 George Street, Shoreditch, with his birth certificate giving his name as Albert Charles. His father was John Ranson – the birth certificate has the name as “Ransom”, but the “m” has been amended to “n”. His mother is shown as “Elizabeth Ranson, formerly Watson.” John’s profession is shown as that of a gilder. The birth was registered by Elizabeth, who was unable to write, and signed the certificate with an “x”.

Lofts and Adley’s suggestion that Charles Dare was born in 1858 (see earlier) does not stand up – while there were a few Charles Dares born around then, their lives can be traced via census and other records, and none of them match with what is known about Dare.

Later census records suggest that both John and Elizabeth were born in Shoreditch in around 1830. Unfortunately, there were several John Ransons and John Ransoms born in and around that area of London in around 1830, and it is impossible to identify one as Charles Albert Ransom’s father. However, the 1901 census records both John and Elizabeth having been born in Bethnal Green. There are two birth records for a John Ranson born in Bethnal Green in 1831: a John Ranson whose parents were Thomas and Mary, and a John James Ranson, whose parents were James John and Charlotte. The first John Ranson appears to have married Elizabeth Parsons Thomas in Bethnal Green in 1861; John James Ransom married Eliza Nicoll in Bethnal Green in 1853.

Otherwise, there appears to be no marriage record for John Ranson (or Ransom) and Elizabeth Watson, and there is no trace of either in the census records for 1841 and 1851. They do appear in the 1861 census, living at 9 Ebenezer Street, Shoreditch, under the name of Ransom, with John working as a gilder and having four children: Elizabeth, aged 12; Victoria, aged 7; Ann, aged 5; and William, aged 1. John is recorded as a “British subject” (suggesting he was born overseas), aged 34. In 1871, they appear, again under the name Ransom, living at 7 Devonshire Buildings, Shoreditch, with John (age given as 40) working as a gilder, and his second son simply recorded as Charles, aged 6. Also present was another daughter, Rosina, aged 8.

What happened to the four children recorded in the 1861 census is a mystery. A William Ransom, born around 1860, is recorded as having died in 1866, with the death registered in Whitechapel. Otherwise, most of the children do not appear in any future census records, and neither are there any death records. Rosina appears in only the 1891 census, working as a nurse and domestic servant in the household of Henry G.A. Rouse, a civil engineer, in Hornsey, London; and in the 1939 Register, where she is living in Wandsworth, described as a retired nurse, and her date of birth is given as 30 April 1862. She died in Chelsea in 1948.

(Possibly entirely coincidentally, after his death some of Ransom’s collection of penny bloods, story papers etc. were bought by John Medcraft, and in turn, after his death, some were acquired by Ronald E.J. Rouse. Born on 16 August 1922 in Norwich, Rouse was a subscriber to The Collector’s Digest, and occasionally advertised items for sale. He died in 1995. Whether or not Henry G.A. Rouse was a distant relative is not known.)

In the 1881 census Ransom is recorded as C. Ransom, living with his father (J. – a gilder, aged 53) and his mother (recorded simply as “B” – this may have been a mistranscription on the part of the enumerator, or it was shorthand for “Betty” or “Betsy”) at 18 Princes Court, Bethnal Green, and working as a messenger.

On 12 October 1889, as Charles Albert Ransom, he married Ellen Elizabeth Logdon at St. Saviour’s Church, Hoxton. At the time they were both living at 96 Bridport Place, Hoxton, with Charles described on the marriage record as a packer. Charles’s father was recorded as a gilder, and Ellen’s father, Harry Logdon, was a carpenter. Ellen herself was born in 1868 in Holloway, London, her mother being Ann Hogdon, née Fennell. Her father died in 1881, and records show that in May 1883 she, her mother and four sisters were in St. Olave’s Workhouse, Surrey, and were then moved to the Workhouse in Shoreditch.

The 1891 census throws up another mystery. Charles Ransom is shown as aged 22 (i.e. born in 1869), born in Shoreditch, working as a porter and living with his father John (recorded as a gilder and carver) and his mother Elizabeth at 7 Derbyshire Street, Bethnal Green. Also present was his sister, named as Rose, and working as a nurse. His wife was not listed.

However, there is also a record in the 1891 census for Charles Dare, born in Shoreditch in 1867, living at 233 Waterloo Road, Southwark, and working as a tobacconist and bookseller. His wife is shown as Ellen (born in Holloway in 1867) and there is a son, Charles, born in Bloomsbury and aged 8 months. (It was not unknown for someone to appear twice, at two different addresses, in the same census, although why Ransom/Dare should give two different ages is a mystery).

This is the only appearance of a Charles Dare, of the appropriate date and place of birth, in the entire census record. Furthermore, there appears to be no birth record for a Charles Dare in 1890 (or, for that matter, for a Charles Ransom or Ranson), and neither does this second Charles appear in the 1901 and 1911 census records.

Charles Ransom is recorded in the 1901 census as Charles Albert Ransom, living with his wife and the first five of his seven children, at 296 Old Kent Road, and working as a bookseller. Ten years later, the family, now with seven children, was living at 38 Elm Grove, Peckham, with Charles Albert Ransom recorded as a bookseller.

The Ransom children were:

Nellie Rosina, born on 27 June 1892; married

Grant Gordon in 1935, died

1976.

Lily Florence, born on 19 December 1893,

and baptised on 13 March 1907 at

St. Mary Magdalene Church, Southwark.

(The baptism records gives her

Parents’

names as Charles Albert and Nellie, living at 296 Old Kent

Road and

with Charles working as a Newsagent and Bookseller). She

married

Harry Perry in 1948, and died in 1976.

John Augustus, born in 1895, died in

1920.

Kathleen Anne, born on 27 January 1898; married

William Morgan in 1958,

died 1979.

Winifred, born on 2 October 1899, died

1951.

Phyllis, born in 1903; married Lionel

Oliver Terrett 1928, died 1974

Douglas, born in 1905, died 1930

Why Lily was the only one of Ransom’s children to be baptised is a mystery. The 1911 census shows Nellie Rosina and John Augustus, then aged 18 and 15 respectively, working as bookseller’s assistants.

John’s father was recorded in the 1901 census, as John Ranson, living at 93 Wellington Row, Bethnal Green, and working as a gilder and carver, along with his wife Elizabeth, with both giving their place of birth as Bethnal Green.

There is no trace of John Ranson (or Ransom) in the 1911 census, although there is an Elizabeth Ransom, a widow aged 82 (therefore born around 1829/30) in the Shoreditch Workhouse, although her place of birth is given as “Somerset ?”.

From 1913 onwards, C.R. Ransom’s family lived at 23 Ephraim Road, Wandsworth, and by 1920 they had moved to 43 Cottenham Park Road, Wimbledon.

In the 1921 census the entire family is recorded at 43 Cottenham Park Road with Charles recorded as a bookseller at 26 Paternoster Row; his wife and daughters Nellie and Winifred recorded working on “home duties”; Lily recorded as a clerk at the Central Telegraph Office; Kathleen as an unemployed secretary; Phyllis as a shorthand typist working for the Gardeners’ Chronicle in Tavistock Street; and Douglas, then aged just under 16, working as a clerk for C.A. Ransom & Co., Wholesale Bookseller, at Queen’s Wharf, Bankside.

Charles Ransom’s wife Ellen died on 7 May 1929, leaving a small estate of £62 1s 3d. Three years later, in June 1932 at Eastry, Kent, Charles married Elizabeth Ruthby (or Ruthbie) Downie. Her genealogy is very sketchy. The Civil Registration Death Index gives her date of birth as 16 July 1889 – however, there is no corresponding entry in the Civil Registration Birth Index, or in any other birth lists. Neither does she appear in any of the census records following her birth. She is recorded living at 20 Jenner House, Hunter Street, St. Pancras, in the 1927, 1928 and 1929 Electoral Registers, and an Elizabeth Ransom, a widow who gave her date of birth as 15 January 1889, is recorded in the 1939 Register living at 43 Pier Road, Littlehampton, Sussex. She died on 29 February 1976, her home address being Netheren, Coulsdon, Surrey, leaving an estate valued at £6,762.

In the meantime, Charles Albert Ransom had died on 19 June 1939, at 43 Cottenham Park Road, Wimbledon, leaving an estate valued at £63,915 14s 6d (around £4 million in today’s terms). He did not, however, leave a will, and Letters of Administration were granted to his widow Elizabeth, his daughter Helen Rosina Gordon (actually Nellie Rosina), and his daughter Lily Florence Ransom.

Ransom as a collector

C.A. Ransom was well-known as a collector of penny bloods, penny dreadfuls and boys’ papers, and he was also regarded as something of an expert. He is listed in the acknowledgements in Montague Summers’s A Gothic Bibliography (1941), and he is also mentioned several times in letters from J.P. Quaine, an Australian bookseller and collector, to Stanley Larnach, another Australian collector – Ransom was one of Quaine’s early correspondents.

He was also mentioned in a poem, “The Old Boys’ Book Brigade”. written by Frank Jay and Barry Ono and published in Vanity Fair, No. 11 (1918) (reprinted in The Collector’s Miscellany, No. 10, September 1947), celebrating dealers and collectors:

….. While Ransome (sic) still can make a show,

Somewhere in Paternoster Row……

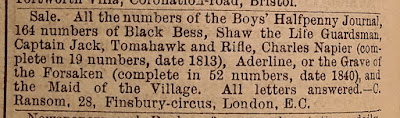

Ransom was clearly a collector, and a fledgling dealer, from a very early age. His earliest known advertisements, offering items for sale or exchange, appeared in The Boy’s Standard (published by Charles Fox) in 1882, when he was around 15 years old, with his address given as 58 Old Castle Street, East London. In 1883, he was advertising (in The Boy’s Standard) from 28 Finsbury Circus; in 1884 he advertised from 30 Charles Street, Stepney (as C.A.R., Chas. A. Ransom and Charles A. Ransom); and in the second half of 1885 he was advertising from 1 Bailey’s Lane, Stamford Hill. In 1887 he advertised from 1 Beaconsfield Terrace, Brondesbury. It is also worth noting that similar advertisements, from “C.R.” and “Ransom,” were placed The Boy’s Standard in 1886 from 12 Ashburnham Road, Bedford.

All of these addresses were private residences, and largely occupied by working class households. Taking each of the above addresses in turn, in the 1881 census their occupants were two households totaling ten people, headed by a bootmaker and a carman; one household headed by a police constable with a wife, son and a servant (he was still there in 1891); two households, headed by a stevedore and a railway porter, and with 11 occupants altogether; one household comprising a bootmaker, his wife and six children; and two households, both headed by gardeners, with 11 occupants in total. In complete contrast, the address in Bedford comprised a retired magistrate, six of his relatives, two visitors and four servants.

Why Ransom used these addresses is another mystery. It is possible that at the times in question he was actually living at each address, as a boarder or lodger, which would suggest he’d left home before he’d reached the age of 15. Alternatively, he knew the occupiers and used their homes as accommodation addresses.

Some of his advertisements offered a mouth-watering range of items, for example this from 12 July 1884:

For Exchange or Sale, cheap, 2nd series Mysteries of London, 2nd, 3rd, and 4th series Mysteries of the Court; The String of Pearls, or Sweeney Todd, the Barber of Fleet-street; Obi, or Three-fingered Jack; Ada, the Betrayed, or the Murder in the Old Smithy; Ella, the Outcast, and others; also a good violin and bow. All the above books are in penny numbers. – Charles A. Ransom, 30 Charles-street, Stepney, London, E. All letters answered.

As a collector, Ransom became very well-known. Lofts and Adley wrote that he was “known to all as Charlie,” and that he “had a very large house at Wimbledon, wherein he housed one of the finest collections of Victorian boys’ papers known…..”

After his death, some of his collection was auctioned at Sotheby’s in November 1939. Amongst the items sold were copies of Black Bess, or The Knight of the Road (3 vols.), about 300 of Dicks’ Standard Plays, several volumes by Thomas Peckett Prest, George Reynolds’s The Mysteries of the Cries of London (8 vols) and The Mysteries of London (6 vols), The Wild Boys of London (2 vols), and works by Pierce Egan, Eugene Sue and Charles Dickens. According to The Collector’s Miscellany (Spring 1941) what was left of his collection was subsequently destroyed in a fire, along with his business premises.

As well as penny bloods and boys’ story papers, Ransom also collected playbills, dramas and books on the theatre, many of which were included in the Sotheboy’s auction. These were almost certainly acquired by M.W. Stone, who wrote extensively about juvenile drama – George Speaight alluded to his holdings of theatrical material which included “another very good collection from the late Mr Ransom, which included a large number of play bills and other theatricalia of the period.” (Juvenile Drama: The History of the English Toy Theatre, Macdonald & Co, 1946, page 194).

Ransom as a bookseller

By 1893 Ransom had become an established bookseller, with premises at 21 Bath Street, City Road, Shoreditch, where he was advertising as a “Dealer in Secondhand Boys’ Books and Journals,” for example in an advertisement in the 11 February 1893 number of The Boys’ Weekly Novelette (published by Charles Fox). Ransom ended the “for sale” portion of his advertisement: “Don’t forget, Boys, I am THE OLD ORIGINAL Boys’ Book Dealer. Established ten years in the Boy’s Standard.” This was demonstrably true, although again it should be pointed out that he was under 15 years of age when he started out. Towards the end of his advertisement, after advertising for items he wanted to buy, Ransom claimed “Established 1875.” This cannot have been the case – Ransom would only have been 8 years old at that time. His advertisement also claimed that he had “the largest stock of Boys’ Books in London…..Any kind of Books bought in any quantity…..Business hours 8 a.m. to 10 p.m.” He also stated that he supplied the trade, suggesting that there were other similar dealers.

Presumably, his buying and selling activities in the 1880s were a hobby or a spare-time business. When he married in 1889, aged 22, he was working as a packer, and in 1891 he was working as a porter. He first appeared in the Post Office Directory in 1892 as a newsagent at 233 Waterloo Road, under the name of Charles Ransom. A year later, as Charles Albert Ransom, he was listed as a newsagent at 21 Bath Street, City Road. In 1895, he established himself as a bookseller at 296 Old Kent Road, where he remained until 1911, having also opened [premises at 26 Ivy Lane, Bermondsey, in 1910. In the meantime, he had also opened premises at 26 Paternoster Row in around 1907, from where, under the name of Charles Dare, he was advertising for musicians and performers.

In 1911, as Charles Albert Ransom & Co., he was listed at 26 Paternoster Row, where he remained until his death in 1939. In 1914 he was also listed as a bookseller at 18 Cock Lane, Smithfield; and in 1915 his Post Office Directory entry began recording his business as “Booksellers, publishers’ remainders (wholesale and export).” In 1917 he opened new premises at Queen’s Wharf, Bankside, which he again maintained until his death.

In 1922, his drectory listings began referring to the business as simply “publishers’ remainders.” A further expansion in the business occurred in 1935, when he was listed as also occupying 62 Park Street, Borough Market. The business closed down immediately after Charles’s death in 1939, with The London Gazette announcing a call for any creditors against Ransom’s estate on 22 December 1939.

On 29 March 1902 The South London Chronicle reported that Ransom, of Old Kent Road, had been fined 5 shillings and costs for “throwing waste paper on the carriageway.”

In 1904, Ransom’s business at 296 Old Kent Road was the feature of a brief article in The South London Press (2 July):

Mr Ransom keeps a very large stock of Cheap Books in all manner of bindings and editions, and all at discount prices. Some modern novels are even cheaper. For instance, you can buy a sixpenny paper-back for 2½d. All the magazines can likewise be regularly supplied at this address, and Mr Ransom also buys or exchanges books and novels, while all kinds of playing cards, games, dominoes, draughts, and so on are kept in stock. Mr Ransom is also a tobacconist, and sells all packet tobaccos and cigarettes at discount prices.

The 1939 Register has Nellie Rosina, using the name Helen, living with her husband, a civil service clerk, living in Chancery Lane, Holborn, working as the manageress of a wholesale bookseller (presumably her father’s company).

Ransom as a publisher

C.A. Ransom’s career as a publisher seems to have begun in 1928, when he began issuing comics. These were actually reprints of old comics – The Golden Penny Comic and The Monster Comic – previously issued by Fleetway Press, founded by Harold Mansfield, a former editor at the Amalgamated Press. Ransom had acquired the original plates at around the time the Amalgamated Press bought out Fleetway Press, but as the titles were now owned by the Amalgamated Press Ransom had to think of new titles. Lofts and Adley wrote that “When C.A. Ransom decided to launch his series of comics, he visited Mr T.J. Adley (father of Derek) at his printing company, W. Speight & Sons Ltd., with a view that he could get his proposed complete range of comics printed by them, as this company had spare capacity on their machines. Speight’s welcomed the idea as this represented a hundred percent profit to them.” Lofts and Adley went on to suggest that Ransom hoped, if the project was a success and resulted in serious opposition to the Amalgamated Press, they would offer to buy him out, although in retrospect this was rather unrealistic.

Ransom went on to turn what had once been two comics into six comics, although their quality left much to be desired. Bill Lofts and Derek Adley wrote that “…..some of the old blocks had gone missing and one had in some of the serials the author’s name lacking, and even some of the strips were printed without titles….” Lofts and Adley stated that the first issue of each comic was undated, and after dates were inserted they were subsequently withdrawn, presumably so that they would never appear to be out-of-date. Denis Gifford, in his 1982 British Comics and Story Paper Price Guide, stated that the run of comics started on 17 September 1928, and ended, after 28 numbers (with some serials unfinished), on 20 April 1929, although Lofts and Adley noted that Gifford had subsequently acquired a copy of Sunny Comic numbered 46.

The six comics were Cheerful Comic, Happy Comic, Merry Moments, Sunny Comic, Tip Top Comic and Up-to-Date Comic.

They were not sold through newsagents and other traditional outlets, and Ransom instead sold them wholesale to distributors, who in turn sold them on to street sellers and traders. Lofts and Adley noted that while the retail price of each comic was twopence, they were “sold as low in the street markets as six for twopence in ‘bargain bumper bundles’.”

Ransom also published a series of cheap paperbacks – 16 novels by Edgar Wallace and three Tarzan novels by Edgar Rice Burroughs:

Edgar

Wallace: The Cat Burglar, The Governor of Chi-Foo, The Little Green Man, “Smithy”.

Eve’s Island, The Daughters of the Night, The Million Dollar Story, Nobby, The

Prison-breakers, Circumstantial Evidence, Fighting Snub Reilly, Barbara on her

Own, Bones of the River, Tam, The Clue of the Twisted Candle and The Four Just Men.

Edgar Rice Burroughs: Tarzan of the Apes, The Return of Tarzan and The Son of Tarzan.

The Tarzan stories had originally been published in the UK by George Newnes in 1929, and Ransom acquired the secondary English rights and also bought Newnes’s printing plates, although the three Ransom editions were issued with new covers. It is almost certain that the same happened with the Edgar Wallace titles. None of the books were dated, but it is thought they were issued in 1929 and/or 1930.

He appears not to have advertised any of these books in newspapers or trade papers, and presumably, like his comics, they were sold by street vendors and similar outlets.

Ransom as theatrical impresario

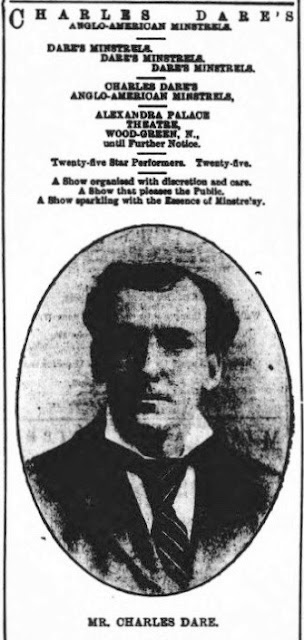

It is not known when C.A. Ransom, using the name Charles Dare, first entered the entertainment business, where he specialized in minstrel shows. He started off in the Moore and Burgess Minstrels, which had been established in 1865 and which performed continuously at St. James’s Hall, Piccadilly for 35 years. The earliest reference to him as a manager of a troupe of minstrels appears to be an advertisement in The Gravesend Reporter (26 November 1892) for “The Celebrated Reynolds and Dare’s Anglo-American Minstrels”, Reynolds being Harry Reynolds. In his history of minstrelsy, Minstrel Memories: The Story of Burnt Cork Minstrelsy in Great Britain from 1836 to 1927 (Alston Rivers, 1928) Reynolds described how he and Dare had first teamed up in a double act for variety shows, and then, having “mortgaged most of our worldly possessions,” started their own minstrel troupe in 1892. This was at the same time as Ransom was establishing himself as a bookseller. They performed on tour until around July 1893, when the partnership was dissolved and Dare accepted an engagement to tour with the Moore and Burgess Minstrels. He also seems to have been performing and touring by himself, with The Isle of Wight Recorder (8 July 1893) describing him as “the popular comedian and farmyard mimic.”

In August 1894 he advertised for vocalists and musicians for his Ryde Pier Minstrels (performing at the Pier Pavilion on the Isle of Wight), and in 1895 he established a minstrel troupe on the Isle of Man, Charles Dare’s Douglas Head Minstrels. In June 1895 he advertised (The Era, 15 June 1895) that he had the “sole permission for Minstrels at Douglas,” giving his address as 12 Church Street, Greenwich. He leased the open air theatre at Douglas Head and staged minstrel shows there until 1912, when he moved his base to the Happy Valley Arena at Onchan Head, Isle of Man, although he was only there for two summer seasons. After each summer season, he took his minstrels on tour in the UK and Ireland.

By 1901 he was advertising Charles Dare’s Anglo-American Minstrels, from 296 Old Kent Road, and in 1902 he also established a troupe of Ethiopian Minstrels, which survived for at least 11 years.

In the meantime, in 1905 he purchased the Mona Theatre at 7 Regent Street, Douglas, and re-named it the Empire Theatre, where he staged variety shows, minstrel shows and the occasional film show. It was re-named the Empire Picture Playhouse in 1913, exclusively showing films. In November 1915, C.A. Ransom & Co., at 26 Paternoster Row, advertised the lease as being for sale.

Despite this, Dare then opened the Coliseum Cinema in Leigh-on-Sea, Essex, in 1914, and kept this going for several years. On 20 August 1932, The Daily Herald reported that Dare (“of Cottenham Park Road”) was fined £5 on each of four summonses, with three guineas costs, for keeping the cinema open after 10 pm on Sundays. He seems to have given it up shortly after this.

He also acquired the Hippodrome Variety Theatre in 1920 or 1921, changing its name and function to the Hippodrome Kinema, but in October 1923 he was advertising the freehold as being for sale.

Interestingly, Harry Reynolds, who knew Dare very well, seemed to have been wholly unaware of Dare’s other life as a bookseller/collector, as he does not mention this in book. He simply wrote that Dare retired from stage “to become a successful cinema proprietor.”

He also published minstrel songs – for example, The Era on 22 October 1910 carried an advertisement for C.A. Ransom & Co. of 26 Paternoster Row which included a note that Ransom were “Exclusive Publishers for Charles Dare’s Minstrels’ Songs.”

Ransom/Dare in 1891 census

Conclusion

There seems little doubt that C.A. Ransom and Charles Dare were the same person. But several questions remain. Why the change of surname from Ranson to Ransom? Why did Charles reverse his first two names? What happened to Charles’s four siblings? Why did Ransom use several different addresses between 1882 and 1887? Why did both Ransom and Dare appear in the 1891 census, and why did Charles Dare give his occupation as bookseller? Why did Charles’s mother end up in a workhouse? Who exactly was his second wife?

Ransom established his bookselling business in around 1892, yet at the same time, as Charles Dare, he was running a troupe of minstrels and performing all over the country. In 1895 he began a long association with the Isle of Man, which ended in 1914, when he moved his interests to Leigh-on-Sea, where he managed a cinema for almost 20 years. Could he really have done all this while at the same time running a bookselling business? Or was the business left in the hands of his family and other assistants? The only members of his family that can be confirmed as working for him were his daughter Nellie Rosina (from around 1910 to 1939), son John Augustus (from around 1911 till his death in 1920), and son Douglas, from around 1920 until his death in 1930.

Comparisons can obviously be drawn between Ransom and Barry Ono, the self-styled “Penny Dreadful King,” who was a contemporary of Ransom (albeit nine years younger) and who had a career as a musical hall comedian and singer and as a bookseller. Born Frederick Valentine Harrison, he changed his name to Barry Ono around the time of the outbreak of the First World War, and performed, on and off, up until around 1930. During lean periods he set up as a shopkeeper under his real name, selling cheap books and periodicals, and then becoming a full-time dealer in the early 1930s. At the same time he had been building up his collection of penny dreadfuls and boys’ papers, which was donated to the British Library after his death in 1941. The main difference between Ransom and Ono is that Ransom’s careers, as musical hall artiste and bookseller, were concurrent, whereas Ono concentrated on bookselling when he wasn’t performing, and after he had retired from the stage.

Despite all the evidence, it is still hard to believe that Ransom had such a busy double life. It is, of course, not beyond the realms of possibility, but it is still something of a mystery.

FOOTNOTE: The Tragic Case of Florence Ransom

Charles Ransom’s second son, Douglas, married Florence Iris Ouida Guilford in Southwark in April 1926. Florence, born in 1904 in Preston, Lancashire (and baptised at St. Anselm’s Church, Kennington Cross, London, on 11 December 1904), was the daughter of Frederick Guilford, a portrait painter, and his wife Mary Blanche, née Doyle (who split up after Florence’s birth). The couple moved to 55 Stuart Road, Wimbledon, but Douglas died just over four years later, from cancer, malnutrition and kidney failure, on 8 July 1930, at his parents’ home in Cottenham Park Road. (His death certificate described him as a publisher’s traveler). He left an estate valued at £435.

It is not known what Florence did immediately after this, but in 1934 she met Walter Lawrence Fisher. Born in London on 7 July 1886, he was a mechanic by trade and since 1914 he had been editor of Automobile Engineer. He had married Dorothy Pound in 1913, settling in Richmond, but after having two children the marriage broke down, although they remained living together. In 1932 they moved to 9 Rosslyn Road, Twickenham, where Dorothy took in a lover. From 1934 onwards Florence was a frequent visitor to the family home, and the Fishers remained on good terms.

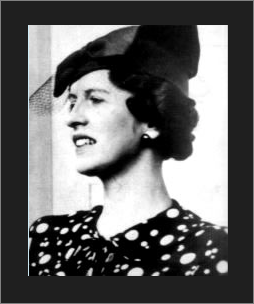

Florence was, by all accounts, a small but striking woman, who claimed to be a changeling and had an aristocratic background, telling some people her real name was Iris Cornwellis-West.

In 1938 Walter Fisher bought Carramore Farm, in Piddington, a village near Bicester, Oxfordshire, where he spent his weekends. The 1939 Register shows the Fishers living at 9 Rosslyn Road, along with their younger daughter Freda (born 9 October 1919), Charlotte Saunders, a 45 year-old cook and housekeeper, and Dorothy’s lover, Steffen Watergaard (who was Danish), a newspaper and publisher’s representative. Walter was recorded as a “Technical journalist and weekend farmer.”

Walter subsequently acquired a cottage, “Crittenden,” in the Kent village of Matfield, to where Dorothy and her lover, along with Charlotte, moved, while Walter and Florence moved permanently into the farm, with Florence calling herself Mrs Fisher. She arranged for several servants to be employed, amongst whom were her widowed mother, brother Frederick (a cowman) and his wife Jessie (a dairymaid), although Walter was unaware of their family relationship. After war broke out, Walter frequently visited Dorothy to make sure she was all right, as Kent was a target for German air raids.

The precise reason for what subsequently happened will never be known. Florence may have turned against Dorothy when she refused to divorce Walter, or she may have been concerned that Dorothy or Freda had discovered her true background, or she may simply have been jealous of Dorothy receiving so much attention from Walter. What is known, however, is that on 9 July 1940 Florence borrowed a shotgun from her brother (who had earlier taught her to shoot), caught a train to London and then another train to Tonbridge, and then travelled on to Matfield. There she shot and killed Dorothy and Freda Fisher and Charlotte Saunders.

The evidence suggested that Frances, Dorothy and Freda had gone into the orchard to shoot rabbits. Freda was shot first, in the back at close range. Dorothy tried to run away, but was shot twice, once in the back and then in the neck. Florence then returned to where Freda was lying and fired two more shots into her back. She then returned to the cottage and shot Charlotte in the head. She then returned to Piddington.

Later in the day the bodies were discovered by the gardener employed by Dorothy’s mother, who had been expecting her daughter for tea and who had sent the gardener to investigate. The cottage had been ransacked, although nothing appeared to have been stolen. It didn’t take too long for the police to suspect Florence (Walter Fisher and Steffen Wattergaard were ruled out very quickly as they had foolproof alibis), although all the evidence against her was circumstantial. The only evidence at the murder scene was a single pigskin glove found in the orchard, which was later shown to fit Florence’s hand. It was assumed that she had dropped the glove when removing the first of the discharged shotgun cartridges. None of the cartridges were ever found, and neither was the other glove, despite a search of the farm at Piddington. Various witnesses, including farmworkers, shopkeepers, a taxi driver and a ticket collector, described seeing a woman of Florence’s appearance carrying a long, narrow brown paper parcel under her arm on the day of the murders.

Florence was charged with the murders on 15 July 1940, and after a series of remand hearings (and after Florence had spent some time in the hospital at Holloway Prison following a nervous breakdown), she was committed to the Old Bailey to stand trial. The first hearing, on 23 September 1940, was adjourned so that her defence barrister could have Florence examined by a neurologist. The trial then began on Thursday 7 November. One minor point of interest is that this was the first murder trial in which the jurors were allowed to go home for the weekend rather than be obliged to stay in a hotel, a provision introduced because of the danger from air raids.

The prosecution called several witnesses, including Walter Fisher and Florence’s mother, both of whom gave damning evidence as to Florence’s behavior on the evening of the murders. The only defence witness was Florence herself, who denied any involvement, adding that her memory of the day in question was a complete blank. Some evidence of Florence’s mental instability was put forward, including that she had occasionally been a voluntary inpatient in hospitals and mental homes. However, this was insufficient, and on 12 November 1940 the jury took just 47 minutes to find her guilty. The judge had no option other than to sentence her to death.

Because of the outbreak of the Second World War, the earlier court hearings received little press coverage, but by the time of the Old Bailey hearing, the worst of the London bombing was over, and the verdict and death sentence received a lot more attention from the newspapers, with many reports highlighting Florence’s demeanor and appearance, and her shocked reaction to the verdict. An appeal was submitted, on the grounds that insufficient regard had been had to the possibility that Florence was clinically insane, but on 9 November 19040 the appeal was dismissed, with Florence again reacting hysterically in the dock. However, the Home Secretary asked for a medical inquiry, and on 21 December she was judge to be insane, the death sentence was commuted, and she was committed to what was then Broadmoor Criminal Lunatic Asylum in Crowthorne, Berkshire.

As “Daphne Brent,” Florence Ransom performed in several plays put on by Broadmoor inmates, all open to the public. One of these was a performance of the musical comedy The Earl and the Girl by Seymour Hicks, staged on 3 March 1948, after which the Evening Standard told its readers that “Daphne Brent” had played her part “with an aplomb that would have startled many experienced actors and actresses.” The Sunday Mirror also recorded that a Broadmoor warder had told its reporter that “Some of us can’t believe she’s not normal.”

Florence Ransom was discharged from Broadmoor in

January 1967, aged 63. She moved to Cardiff, where she died, at 174 Albany

Road, Roath, Cardiff, on 16 December 1969. Her probate record gave her name as

Florence Iris Ouida Guilford, and she left an estate valued at £139 (just over

£2,000 in today’s terms).

No comments:

Post a Comment