The first of our two Furniss’s is

Henry Furniss, caricaturist, journalist, and illustrator, who was known affectionately as

“Harry.” Henry was born 26 March 1854 in Wexford, Ireland. Henry, who signed himself “Harry” for the census-takers, was, and is, often confused with

Harold Furniss, caricaturist, journalist, illustrator, and collector of criminal literature.

Harold Furniss

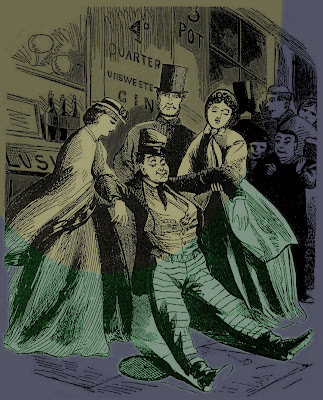

Harold Furniss was born in Birkenhead, a town on the river Mersey opposite Liverpool, in 1856. In 1901 Harold was residing in North Wimbledon with a wife May Furniss, born in Newcastle, Surrey, aged 30, and an 8 year old son, Harold, born in London Forest Gate, Surrey, in 1893. Unlike the social climbing Harry, who dined with Gladstone and seated himself at the Punch table, Harold was an inhabitant of sub-literary London. He was from the Tom and Jerry school of journalism, a penny-a-liner specializing in crime and boxing. Artistically he was a police-court portraitist, political caricaturist and illustrator of risqué prints.

Harry Furniss

Harry Furniss began cartooning for the Irish comic journal “Zozimus” in 1873, at nineteen years of age. He moved to London where he was employed on “The Illustrated Sport and Dramatic News” and “The Illustrated London News.” His cartoons and illustrated articles appeared in “The Graphic,” “Black and White,” “Good Words,” “Pall Mall,” “Pearson’s,” “The Strand” and “The Magazine of Art.” On 3o October 1880 he began contributing to “Punch.” The volatile artist quit “Punch” and produced his own comic periodical “Lika Joko” in 1894. ‘Lika Joko” failed and was followed by other short-lived papers like “New Budget” (1895,) “Fair Game,” and “The Cartoon” in 1915.

Harry Furniss

Harry Furniss was a strange man, a prickly paranoid with an explosive temper. He became annoyed with the proprietors of “Punch” when they licensed his famous cartoon for Pear’s Soap advertisements. The cartoon featured a scruffy bum writing to a soap company, saying, “I used your soap two years ago; since then I’ve used no other.” The celebrated Canadian cartoonist A. G. Racey reminisced to “Maclean’s” magazine on October 1, 1925 in a long chatty article titled “A Cartoonist Looks at Life” >

“I tell you a most entertaining fellow,” he continued, sawing away at his steak. “Harry Furniss, the famous artist of Punch. He is dead now, but when he was in Montreal I took him out one evening to see the city. Just as we left the hotel the fire reels passed, and I thought a fire-fighting scene would be a good start for the evening’s entertainment. But when I turned round Furniss had disappeared. He came back in a few minutes with his coat tightly buttoned, and a large bulge showing on each side . “What have you got there?” I asked. He unbuttoned his coat and displayed two huge army revolvers and a belt of cartridges. Fear of arrest forced me to request him to leave his artillery behind. “But look here,” said Furniss, “is it safe to go about Montreal unarmed, what ?” Later I found he had a regular arsenal in his room, as well as fur coats and so on. They were for use in August and September in Canada.

“Furniss expressed a wish for some hunting and fishing in the north woods, so a friend and I took him up the Saguenay to the Shipsaw river, up which we went for a hundred miles or so. We left Chicoutimi and drove fourteen miles with our guides and canoes to Dufour’s farm, which was the last in civilization. The house was too full to accommodate us so we set up our tents nearby and soon were fast asleep in our blankets. Very early in the morning I was awakened by Furniss, who was sleeping next to me. He was poking me excitedly in the ribs. “What’s up ?” I asked. In a tense strained voice he answered, “For heaven’s sake, Racey, look and see if it’s a bear !” Cautiously turning I beheld Dufour’s calf with it’s face inside the tent flap vigorously licking the top of Furniss’ very bald head. Furniss illustrated this incident several times on his return to England. He and Captain Emerson Neilly, V.C., of Boer War fame, who came to spend August in Montreal, also armed for bear and Indian and zero weather, suggested the book of cartoons, ‘The Englishman in Canada’ which I published in 1907.” (‘The Englishman in Canada’ was actually published in 1901.)

Harry was well-aware of the doings of Harold and remarked cryptically in his book Confessions of a Caricaturist, that >

“I should like to confess my real reason for going on the platform. The fact is that for many years I was mistaken in the country , particularly in Liverpool, Leeds, and Bradford, for an artist who signed political caricatures “H.F.” and whose name, strange to say, is Harold Furniss. I understand he is about twice my size. So that I thought that if I showed myself in public, particularly in the provinces, it would be seen that I was not this Harry Furniss.”

The Liverpool Lantern was launched in 1877 by K. C. Spier. According to Athol Mayhew in A “Jorum” of Punch, London: Downey & Co., 1895

“The Liverpool Lantern had its light put out about four years after its illumination, but whilst it flashed it was appreciated on account of the excessively, and sometimes almost painfully, neat process and transfer illustrations of Harold Furniss, and the broadly humorous blocks of “Ant” (Arthur North), a Northern draughtsman, soon to be requisitioned for the pages of The Yorkshireman, a Bradford satirical weekly founded in 1875 by James Burnley…In 1880, Harold Furniss, having seceded from The Lantern, founded The Liverpool Wasp, and at the same time W. G. Baxter -- by-and-by to make an enduring reputation for himself in London in connection with Ally Sloper, and to die in the prime of life and in the zenith of his genius -- was exploiting Momus, in Manchester.

Harold Furniss ran into trouble with

The Liverpool Wasp on August 10, 1881 >

Alleged Libel.- At the Liverpool Police-court yesterday a summons was set down for hearing, in which Harold Furniss, the conductor of a weekly illustrated paper in Liverpool, called the Wasp, was charged with libelling Mr. G. F. Lyster, engineer to the Mersey Docks and harbour board. The libel was an insinuation of deriving pecuniary benefit from certain contracts. It was stated to the magistrate that the summons had not been served, the police not having been able to find the defendant, who had published an apology on Saturday last. The summons was adjourned until the 27th inst.

The Wasp was a ‘satirical journal,’ printed and published by Harold Furniss in Liverpool. There were a large number of previous comic periodicals bearing the same title including “The Wasp” of 1870, described by William Rayner in N&Q for 1872 as “obscene.” It was probably Harold’s dodgy reputation that led Harry Furniss to issue a press release on 1 August 1883 >

“The World has been asked by Mr. Harry Furniss to state that he is in no way connected with an artist signing himself “Harold Furniss” It seems that the two artists have been confounded in certain instances, and that certain sketches issued by “Harold” have been credited to “Harry,” much to his annoyance.”

Harold left Liverpool and environs under a cloud in 1881 and began anew in London. In 1886 Harold’s caricaturist and journalistic skills were put to good use as a penny-a-liner and quick sketch artist in the London Police Courts. This activity led to his illustrating a Crim.Con classic titled “The Campbell Divorce Case, Copious Report of the Trial. With Numerous Portraits of Those Concerned, Drawn from Life,” published in London by Palmer & Co., Bolt Court, Fleet Street, E.C. at 154 pages. This infamous divorce case involved Lady Campbell accusing her husband of adultery, and he retaliating by charging her with adulterous relations with several men. George Purkess Jr., proprietor of The Illustrated Police News published another 16 page penny version on the subject in January 1887, “The Colin Campbell Divorce Case,” with several portraits included.

By 10 June, 1893 Harold was editor, author, and artist on the penny “Illustrated Police Budget,” which touted itself as “the Leading Illustrated Police Journal in England,” in competition with George Purkess Jr.’s “Illustrated Police News.” It was printed and published by Frank Shaw and ran until 1910.

This newspaper account from Thursday, August 16, 1894 must have endeared Harold to Harry even more >

Art or Indecency. Prosecution of an Illustrated Paper. An Offending Picture. >

At Bow-street on Tuesday, William Mole, a newspaper hawker, was charged before Sir John Bridge with exposing for sale and selling an indecent publication, namely a copy of the “Illustrated Police Budget.” Mr. C. Willoughby Williams, instructed by the proprietor, appeared for the paper.

William Donnell, a detective officer, proved having purchased from the prisoner a copy of the paper, dated August 11. He was instructed to make the purchase by Detective-inspector Hare, of Scotland Yard. - Copies of several issues of the paper were placed before Sir John, who said that the principal illustration in one of them referred to a divorce case. The learned magistrate went on to say that the copy which the prisoner was said to have sold contained an illustration of a lady and a gentleman in a boat. The lady’s dress was up to her knees, and the gentleman was supposed to be singing, “I long to linger, linger long with you.” He suggested that the proprietor should promise not to publish things of this kind in the future. They were indecent; there could be no doubt on this point. - Mr. Williams, after consulting his client, said that he would like to call artists who would say that the paper was not indecent.

Charles Waud, who described himself as an artist, was then called. He said he was employed on the “Police Budget,” and sketched the young gentleman and lady in a boat.

Sir John Bridge: Did you sketch it from nature? (Laughter.)

The Witness: I did, partly. The idea was given to me at Henley.

Sir John Bridge: Was the lady’s leg showing as it is here?

The Witness: Her ankle was.

Sir John Bridge: Did you hear her sing “How I long to linger, linger long with you?” (Laughter.)

The Witness: Oh! Yes; it was sung at the Gaiety, and proved a great favourite.

Mr. Williams: You have special instructions?

The Witness: Certainly. The word “indecent” has never been mentioned, but we are told to take care that there is nothing “fast.”

Mr. Williams: What other pictures have I to meet?

Sir John Bridge: You have to meet the whole thing. The whole thing is indecent to my mind.

An artist, named Harold Furniss, employed upon the paper, said that in his opinion it was not indecent.

Mr. Williams (pointing to the boat scene) : Is this indecent?

The Witness: I think it is a charming scene, and worth illustrating.

Another artist, with a German name, gave similar evidence, saying he had been an artist ever since he was born -- a born artist in fact.

Mr. Wallbrook, the printer of the paper, was next sworn, and said he could see nothing indecent in it.

Sir John Bridge called his attention to a certain advertisement, and the witness said he had not noticed that before; if he had, he would have asked the proprietor to remove it. He had, however, seen similar advertisements in a religious paper.

Charles Shurey, the proprietor of the “Police Budget,” said he was most careful as to what appeared in his paper, and he sent an early copy every week to the police, and told them that if they objected to anything he would expunge it. He would never publish an advertisement that had not already appeared in some respectable paper. On an average he refused a dozen advertisements a week. Six months ago he had three or four columns of certain advertisements, but as they expired he declined to renew them.

Sir John Bridge: It does not follow that these things are right because you have seen them in some other publication.- In giving his decision, Sir John Bridge said it was perfectly right to report police-court proceedings to enable people to know what was going on but to illustrate scenes which perhaps had never occurred, and to publish indecent pictures was highly improper. The proper object of the press was to improve, to instruct, and to elevate the people, but the tendency of these pictures and advertisements was to lower, to degrade, and to demoralise. He had no doubt that the real object was to put money into the pocket of the proprietor of the paper. In his opinion it was an indecent publication, and the prisoner would be fined £2 and 2s. Costs. He must not sell it again. No doubt the proprietor would pay the fine. Addressing counsel for the defence, Sir John Bridge expressed the hope that no such illustrations would appear in future.

On March 4, 1901 Vol. I No. 1 of “Famous Fights Past and Present Police Budget Edition” was published in London from Caxton House, Gough Square, Fleet-Street. Harold Furniss edited and contributed journalism, portraits and illustrations. A companion paper was begun in 1903 “ Famous Crimes Past and Present Police Budget Edition” also edited and contributed by Harold Furniss. Volume II, no. 13 had Jack the Ripper on the cover, the continuity was called “Jack the Ripper The Story of the Whitechapel Murders,” lavishly illustrated, by ‘Ferdinand Fissi.’ The author of the Jack the Ripper article is believed to be Harold Furniss. In modern times the text of the four parts have been widely circulated in a photocopied edition.

I don’t know much about Harold Furniss later years. His crime collection was made ample use of by the poet Henry Savage, who called Harold “a brother of the caricaturist, Harry, and head of the Caxton Press,” and his friend Richard Middleton. In “The Edge Of The Unknown,” (1930) Arthur Conan Doyle expressed “my obligation to Mr. Harold Furniss, whose care has restored many details in his collection of criminal records.”

In 1912 Harry Furniss worked for Thomas Alva Edison in the burgeoning cinema industry as writer, producer, and actor then returned to Britain before the world war. He was filmed sketching in 1914 for a war-time propaganda piece called “Pencillings by Harry Furniss” He died at Hastings on 14 January 1925.

*

Thanks to Nick and Steve for the help.