|

| [1] The man in the photograph is Sam Lucas; sheet music cover 1901. |

by John Adcock

“Jazz music evolved in this manner: spiritual, coon songs, ragtime, syncopation and jazz.” — J. Rosamond Johnson

THE DEAN. The Dean of Negro comedians was Sam Lucas, who was born Samuel Mildmay, a free man, in Washington Court House, Ohio on August 7, 1848. His parents were former slaves from Virginia. He had a “rich Virginia accent” picked up from his parents, emancipated southern Negroes who had moved to Ohio before the Civil War. For five years he crossed the fields at night to learn how to read and write from a kindly neighbor lady.

Lucas worked as a farmhand until he was 19 years old. He learned to play the guitar and took up the barber trade in Cincinnati, Ohio. He fought on the Union side during the Civil War. His first job as an entertainer was with Hamilton’s Colored Quadrille Band as a guitarist and caller. In 1869 he taught school in New Orleans for a few months before moving to St. Louis where he joined Lew Johnson’s Plantation Melodists as middle man and balladist. In 1873 he was entertaining customers at a barbershop in St. Louis before joining up with the passing Callender’s Georgia Minstrels troupe that July. Lucas sang in a quartette, provided comedy, and began to write songs. In one skit he caught “an imaginary fly high up on a piece of stage scenery.”

First he crouched against the painted wall. Then he stealthily rose and

rose, and kept on rising, opening up joint after joint as if he were made of

telescopes. Higher and higher he stretched, till his audience thought he would

never stop. And when he finally did reach his utmost extension, standing on

tiptoe of his long feet, with his long arm and his long fingers almost up to

the real stage flies, he looked as if he could tickle a giraffe under the chin.

Sam Lucas fly catching is a tradition of stage funny business.

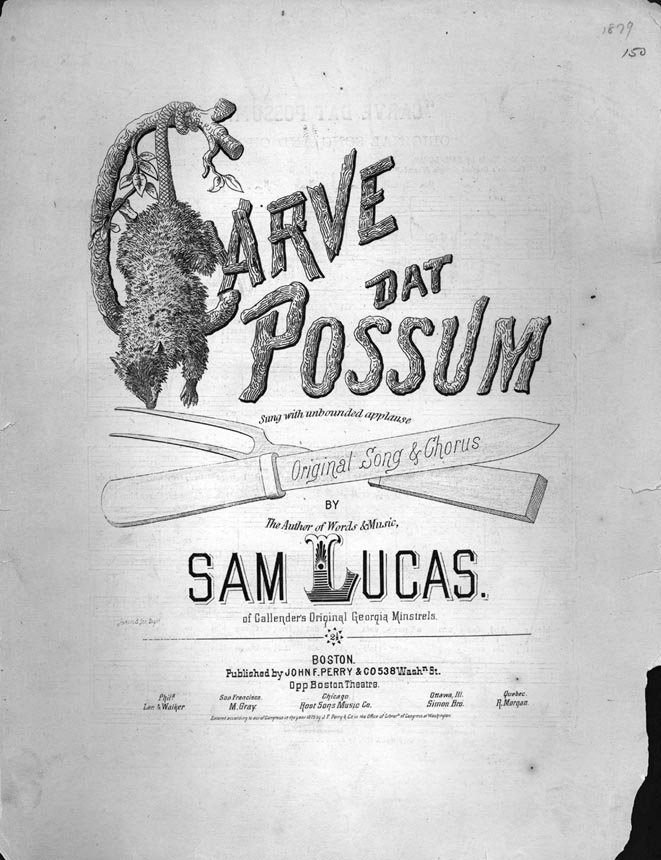

In 1874 Lucas joined the Hyer Sisters in the musical comedy ‘Out of Bondage,’ the first musical show ever put on by a colored organization. In 1875 he was performing his famous song ‘Carve Dat Possum’ at the Robinson Hall on Broadway alongside the comedian Billy Kersands. Now he began working as a singer and dancer in Vaudeville and starred in a blood-and-thunder play called ‘The Black Diamonds of Molly McGuires’ which he described as the first time a Negro starred in a melodrama “surrounded by a white cast.” It was said of Lucas that he was initiated into a white Masonic Lodge before they revised their Constitution.

Sam Lucas wrote ‘Carve Dat Possum,’ ‘Daffney Do You Love Me,’ ‘Dar’s a Lock on De Chicken Coop Door,’ ‘Dem Silver Slippers,’ ‘Every Day’ll Be Sunday By and By,’ ‘I’m Grant and I’ve Travelled Round the World,’ ‘Ol’ Nicker-Demus, De Ruler Ob De Jews,’ and ‘We Ought to Be Thankful for That.’ One 1885 song, ‘De Coon Dat Had De Razor,’ a great grand-daddy to ‘Bully of the Town,’ was written by Prof. W.F. Quown with music by Sam Lucas.

|

| [2] Sheet music cover, 1876. |

De possum meat am good to

eat,

Carve him to de heart;

You’ll always find him good

and sweet,

Carve him to de heart;

My dog did bark, and I went

to see,

Carve him to de heart;

And dar was a possum up dat

tree,

Carve him to de heart.

Other songs Lucas wrote which survived were ‘Turnip Greens’ (recorded by Bo Carter in 1928), and ‘My Grandfather’s Clock.’ Unfortunately black performers of ragtime songs seem rarely to have made it to 78’s. Other than George W. Johnson, whose songs were more traditional plantation melodies the only black artists to record that I know of were Bert Williams and George Walker.

UNCLE TOM. In 1876 Sam became the first black actor to portray ‘Uncle Tom’ on the stage, for C.H. Smith’s Double Uncle Tom’s Cabin Company, first in Cincinnati then in Boston. Mrs. Harriet Beecher Stowe witnessed the performance in her home town and wrote Lucas praising his performance. The next few years made a “fine-feathered bird” out of Lucas. “You never saw such clothes as I had on!” The colored preachers, however, called him “the debbil” and warned their congregations against attending his shows.

He remained with the company until 1879 then toured heading a white cast with the Boston Stock Company. He remained in Boston until 1899, starring in stage dramas and working alone.

In 1891 ‘The Creole Show’ opened with Sam Lucas, Fred Piper, Bill Jackson, Irving Jones and a chorus of “attractive Negro girls.” Alain Locke wrote that this groundbreaking musical show was a “break with minstrelsy” which led to the ragtime coon songs of Ernest Hogan, Cole and Johnson, and Williams and Walker. Coon songs were a precurser of the blues of W.C. Handy, Bessie Smith, Clara Smith, and contemporary jazz.

Lucas married Miss Carrie Melville of Providence, Rhode Island and the two appeared as a musical act in vaudeville. They spent the next three years with Sam T. Jack’s Creole Company (song writer Irving Jones was also a cast member) then spent six years in London, England where Queen Victoria presented him with a large diamond ring. Returning to America they starred in Al G. Fields “Darkest American” company. Lucas played ‘Silas Green’ in Cole and Johnson’s ‘A Trip to Coontown.’

As Negro music and musicians began moving away from minstrelsy about 1895 Sam Lucas moved with the times by performing popular ragtime songs along with black songwriters Gussie L. Davis (‘I’ve Been Hoodoo’d’), Ernest Hogan (‘All Coons Look Alike to Me’), Bert Williams, George Walker (‘She’s Getting More Like the White Folks Everyday’), Ada Overton Walker (‘Miss Hannah From Savanna’), Irving Jones (‘St. Patrick’s Day is a Bad Day For Coons’), Bob Cole and Billy Johnson (‘I Wonder What is That Coon’s Game’) and the Canadian born Shelton Brooks (‘Darktown Strutter’s Ball’).

LAST JOB. Lucas’s last job as an actor was starring as ‘Uncle Tom’ in the 1914 World Film Corporation motion picture ‘Uncle Tom’s Cabin.’ Sam Lucas died January 10, 1916, and his funeral was overflowing with mourners, so much so that a police presence was required to control the crowd. James Reese Europe’s famous Hellfighters band played a final ‘My Grandfather’s Clock’ for the appreciative crowd. His remains were interred in the soldier’s plot at New York’s Cypress Hills Cemetery. He was survived by a daughter, the well-known pianist for the Negro Player’s Orchestra, Marie Lucas.

“I suppose the most famous

song I ever sang was ‘My Grandfather’s Clock.’ And it’s the song I didn’t get

credit for either. I don’t believe the true story of that song is known to most

people. It was written when I was with the Hyers Sisters and this was how it

happened. I was there in New York and went around one day to see a man named

Henry C. Work, the man that wrote ‘Wake Nicodemus!’ Just as I was about to

leave he pulled out a paper and said: “here, Sam; here’s the first verse for a

song. I wrote this one but I can’t seem to make anything more out of it. Maybe

you can.” It was the first verse of ‘My Grandfather’s Clock.’

My grandfather’s clock was too tall for the shelf,So it stood ninety years on the floor,It was taller by half than the old man himself,Though it weighed not a pennyweight more,It was bought on the morn of the day he was born,And was always his treasure and pride,But it stopped short never to go again,When the old man died.

“I read it and took it away

with me, but I didn’t do anything with it for some time. Then one morning when

we were out on the road I got up from the breakfast table at the hotel where we

were stopping and as I turned around there in the corner stood a regular

grandfather’s clock just like the one in the verse Mr. Work had given me.”

And right here, if you

happen to be at Sam Lucas’s home, he will step out into the dining room where a

tall clock occupies one corner and show you just how he stood on that long ago

morning, his hand resting on the table while he looked the old timepiece over

and imagined its story. He wrote the two other verses – one telling how the

clock was the old man’s servant: it never wasted time, there was never a frown

on its face, its hands never hung by its side and all that it asked at the end

of the week was to be wound up for another seven days’ work. The last verse was

the one that described the old man’s death.

“You know,” says Sam, “that

folks are superstitious when a clock strikes more than it ought to. They think

it’s a bad sign, somebody goin’ to die. So I wrote about the alarm ringin’ when

it had been dumb for ninety years. An’ the neighbors all said jest what they

would have said if they’d been the neighbors I had known: they said death was

comin’ to that house. An’ the clock struck twenty four – that meant the whole

round of a life, you see – and then it stopped. And the old man died. Remember

the chorus?

Ninety years without slumbering,Tick, tock! Tick, tock!His life seconds numbering,Tick, tock! Tick, tock!But it stopped – short – never to go again,When the old man died.

“I always loved that chorus”

and Sam picks up a guitar and sings it softly, delicately, lovingly. “Yes, I

wrote that and I wrote the music. I mean I made it up. Yes, just exactly as it

goes. I took the song back to Mr. Work and he published it as his but with my

picture on the front of it, a picture of me standin’ with my elbow on a big

grandfather’s clock. No, I never got a cent for it, except that I had a big

success singin’ it before anybody else did. The royalties Mr. Work received

from that song amounted to thousands of dollars.” – Long Sam Lucas, Artist of

Negro Minstrelsy, in NY Sun, October 22, 1911

UNCLE TOM. In 1876 Sam became the first black actor to portray ‘Uncle Tom’ on the stage, for C.H. Smith’s Double Uncle Tom’s Cabin Company, first in Cincinnati then in Boston. Mrs. Harriet Beecher Stowe witnessed the performance in her home town and wrote Lucas praising his performance. The next few years made a “fine-feathered bird” out of Lucas. “You never saw such clothes as I had on!” The colored preachers, however, called him “the debbil” and warned their congregations against attending his shows.

|

| [3] Photograph of Sam Lucas c.1891. |

In 1891 ‘The Creole Show’ opened with Sam Lucas, Fred Piper, Bill Jackson, Irving Jones and a chorus of “attractive Negro girls.” Alain Locke wrote that this groundbreaking musical show was a “break with minstrelsy” which led to the ragtime coon songs of Ernest Hogan, Cole and Johnson, and Williams and Walker. Coon songs were a precurser of the blues of W.C. Handy, Bessie Smith, Clara Smith, and contemporary jazz.

Lucas married Miss Carrie Melville of Providence, Rhode Island and the two appeared as a musical act in vaudeville. They spent the next three years with Sam T. Jack’s Creole Company (song writer Irving Jones was also a cast member) then spent six years in London, England where Queen Victoria presented him with a large diamond ring. Returning to America they starred in Al G. Fields “Darkest American” company. Lucas played ‘Silas Green’ in Cole and Johnson’s ‘A Trip to Coontown.’

As Negro music and musicians began moving away from minstrelsy about 1895 Sam Lucas moved with the times by performing popular ragtime songs along with black songwriters Gussie L. Davis (‘I’ve Been Hoodoo’d’), Ernest Hogan (‘All Coons Look Alike to Me’), Bert Williams, George Walker (‘She’s Getting More Like the White Folks Everyday’), Ada Overton Walker (‘Miss Hannah From Savanna’), Irving Jones (‘St. Patrick’s Day is a Bad Day For Coons’), Bob Cole and Billy Johnson (‘I Wonder What is That Coon’s Game’) and the Canadian born Shelton Brooks (‘Darktown Strutter’s Ball’).

|

| [4] Sam Lucas, 1911 publicity photo. |

Further reading:

Staging Race, Black Performers in Turn of the Century America, by Karen Sotiropoulos, Harvard University Press, 2006

Staging Race, Black Performers in Turn of the Century America, by Karen Sotiropoulos, Harvard University Press, 2006