The Great Gluyas Williams

On the Happy and Not So Happy

Job of Cartooning

by Rick Marschall

One of cartooning's natural talents, an "artist's artist," the gentle genius Gluyas Williams was asked for an autograph in 1932. He responded to the aspiring cartoonist (named Tom Sanders) with more -- a hand-written letter.

Mr Williams at the time was a nationally admired cartoonist who recently had switched his prodigious work from Life magazine to The New Yorker; also drew for other publications; produced a daily newspaper panel for John Wheeler's Bell Syndicate (many featuring the urbane character Fred Perley); was illustrating many books, most notably the collections of Harvard classmate Robert Benchley; drew advertising art... and much more. An unending fount of brilliant humor, flawlessly executed, and (as the owner of many Gluyas Williams originals, I can attest) drawn almost always perfectly -- that is, almost never a correction or cross-out. Amazing.

There was joy in his work -- or at least satisfaction. He never showed malice, though he focused (and titled) his series "life's little foibles." His was a happy world, inhabited by petite bourgeoise folks, going about everyday tasks with which his comfy middle-class readers identified. He never aimed for slapstick nor guffaws; rather comic irony and chuckles.

In fact, Gluyas Williams told me (for I became a friend at the end of his life) that very early in The New Yorker's days he actually scolded the magazine's founder Harold Ross who wanted one of his submissions to show more physical humor. Mr Williams returned the artwork unchanged and explained that the best humor was understated. Ross agreed, and this exchange possibly changed the trademark tone of New Yorker humor forevermore. Gluyas Williams was a modest man, and I cannot believe this story was an empty boast. Not even a full boast, just a memory of an exchange.

Quietly (the typical mode) Mr Williams slipped into semi-obscurity later in life. Brian Walker of the Museum of Cartoon Art edited the National Cartoonists Society album in the 1970s, compiling biographies of living and dead cartoonists, and listed Gluyas Williams as "deceased." In a Nietzschean sense, to some I suppose he was.

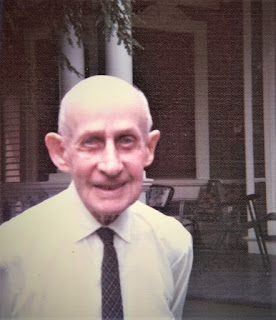

On a visit with Gluyas Williams exactly 50 years ago, I took his photograph. (He was then living in a nursing home, not for any disability of his, but to be with his wife who was infirm.) I interviewed him -- versions have appeared in Cartoonist PROfiles, The Comics Journal, and nemo magazine. I asked him to counter-sign a book he had illustrated exactly 50 years before that -- an "association-piece" that was an inscription by the author, the brilliant Robert Benchley to his fellow Life staffer, Robert E Sherwood, later an award-winning playwright and assistant to Franklin Roosevelt.

Reverting To Mr Williams' fan letter of 1932. "I am very glad to send you my autograph, and I hope that you will realize your ambition of becoming a cartoonist. It's lots of fun (at times) to be one, but there are lots of days when I'd rather be a brick-layer." An urbane reflection of frustration -- perhaps short-lived in Williams World -- not a primal scream but a primal sigh, just as might have been quietly vented by Fred Perley.

It should be noted here that there is no record of a Tom Sanders, whether a young lad or middle-aged aspirant in 1932, afterward being a professional cartoonist. We will check the documents of the brick-laying profession...