|

| [1] PFDA Commemorative Stamps. |

by E.M. Sanchez-Saavedra

Things are seldom what they seem;

Skim milk masquerades as cream;

Lard and soap we eat for cheese;

Butter is but axle-grease.

|

| [2] Neuralgine Advertisement. |

|

| [3] London Morning Post, May 16, 1777. |

|

| [4] Holloway’s Ointment Pot. |

|

| [5] Snake Oil Advertisement. |

|

| [6] Cocaine Toothache Drops. |

|

| [7] Dr. J. H. McLean’s Cordial. |

|

| [8] Parker’s Tonic 1882. |

|

| [9] Heroin Cough Sedative. |

|

| [10] FitzHugh Ludlow. |

|

| [11] Vanity Fair 1862. |

|

| [12] The Day’s Doings, April 23, 1870. |

|

| [13] The Day’s Doings, August 17, 1870. |

|

| [14] The Day’s Doings, April 23, 1870. |

|

| [15] The Day’s Doings, April 23, 1870. |

— Otto L. Bettman, ‘The Good Old Days – They Were Terrible’ (New York: Random House, 1974).

— Barbara Hodgson, ‘Opium; A Portrait of the Heavenly Demon’ (San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 1999).

— Barbara Hodgson, ‘In The Arms of Morpheus; The Tragic History of Laudanum, Morphine and Patent Medicines’ (Buffalo, NY: Firefly Books, 2001).

|

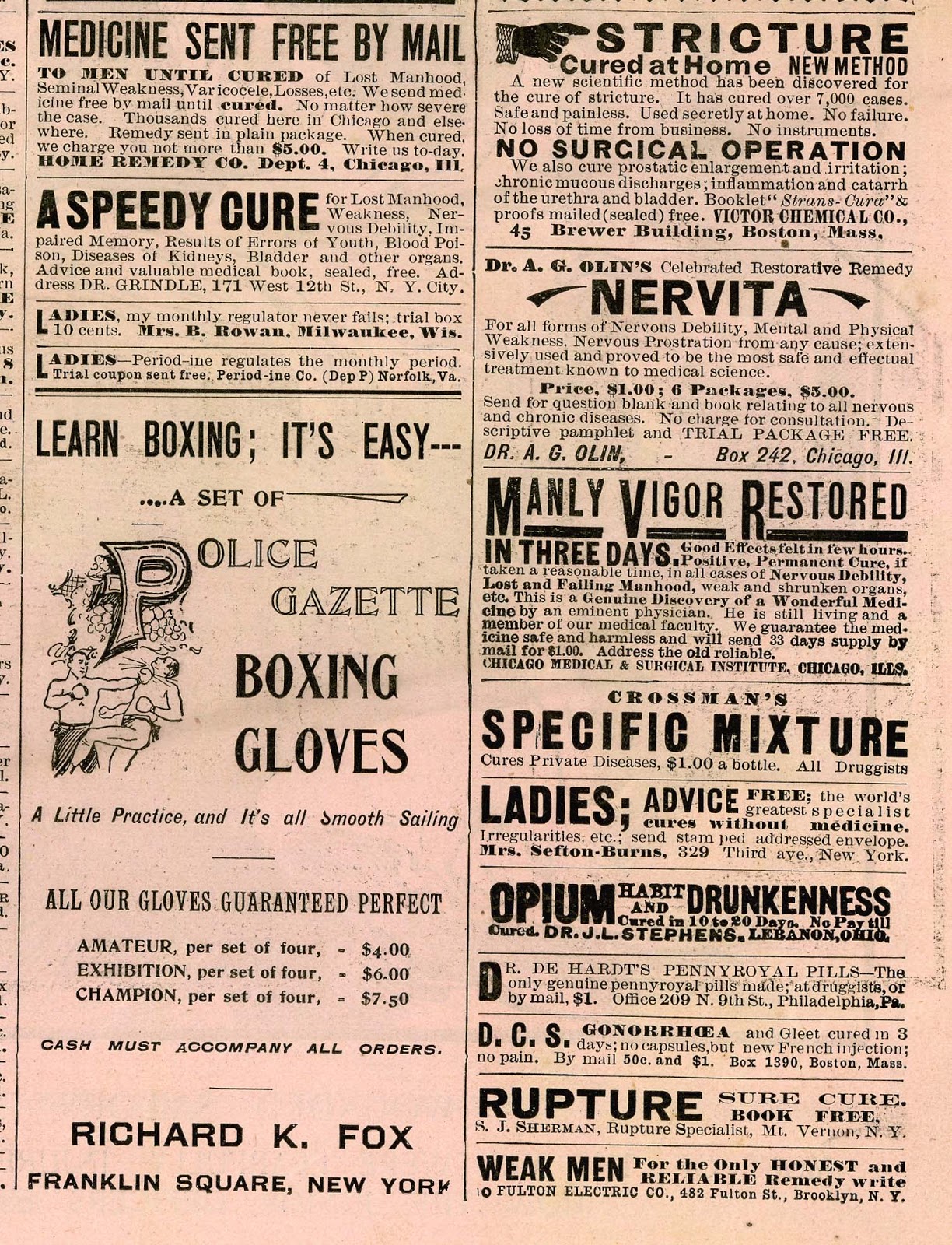

| [16] Police Gazette, December 17, 1881. |

|

| [17] Police Gazette, December 10, 1881. |

|

| [18] Police Gazette, December 10, 1881. |

|

| [19] Police Gazette, March 5, 1898. |

|

| [20] Police Gazette, March 5, 1898. |

|

| [21] Police Gazette, 1898. |

|

| [22] Police Gazette, 1898. |

|

| [23] Coca Cola Syrup. |

|

| [24] J.G. Dill’s Best Cut Plug. |

|

| [25] Allen & Ginter Old Planter. |

|

| [26] Cocarettes Advertisement. |

|

| [27] Bull Durham Label. |

|

| [28] Vinous Rubber Grape Co. Advertisement. |

|

| [29] Malt Whisky Advertisement. |

Great site! I am loving it!! Will be back later to read some more. I am taking your feeds also

ReplyDelete