|

| [1] Cheerful Ching-Ching by E. Harcourt Burrage, 11 Nos., “Best for Boys” Publishing Company |

by Robert J. Kirkpatrick

“And lastly, Ching-Ching –

eccentric, clever, cunning immortal Ching-Ching, whose nature has so many

contradictions in it that one scarcely knows what he is – I, the writer of his

history, fail to fathom him, and it may be that he was even a puzzle to himself?”

– Handsome Harry of the Fighting Belvedere, by E. Harcourt Burrage, 1876

|

| Thomas Harrison Roberts [1850-1915] |

|

| [2] |

In March 1876, Lucas’s Boy’s Standard began serialising ‘Handsome Harry of the Fighting “Belvedere”’ written by Edwin Harcourt Burrage. Born in Norwich, Norfolk, in 1839, Burrage had moved to London, and after a brief and unsuccessful spell as an engraver was encouraged to try his hand at writing by Charles Stevens, the original editor of Edwin J. Brett’s Boys of England; himself a successful author of boys’ stories. Burrage submitted a story to William Emmett, then establishing himself as Brett’s great rival as a publisher of boys’ story papers, and after having it accepted was soon appointed as a sub-editor on the Emmett paper the Young Briton, in 1869. Burrage subsequently wrote numerous stories for various Emmett publications, most notably a series about Tom Wildrake, a character created by George Emmett in March 1872, in Tom Wildrake’s Schooldays, the authorship of which was taken over by Burrage in August of that year when Emmett allegedly ran out of steam. Many of Burrage’s later stories appeared under the name of George Emmett.

|

| [3] |

The publishing history of Ching-Ching’s Own is rather confusing, not least of all because of mistakes made by previous bibliographers – myself included. To begin with, both Frank Jay (in in his series of essays on 19th century periodicals ‘Peeps into the Past’) and John Allingham (in his ‘A Brief History of Boys’ Journals’) stated that Ching-Ching’s Own was launched on 14 June 1888. However, the British Library has a complete run of the paper, and the first number is clearly dated 23 June 1888, a Saturday.

|

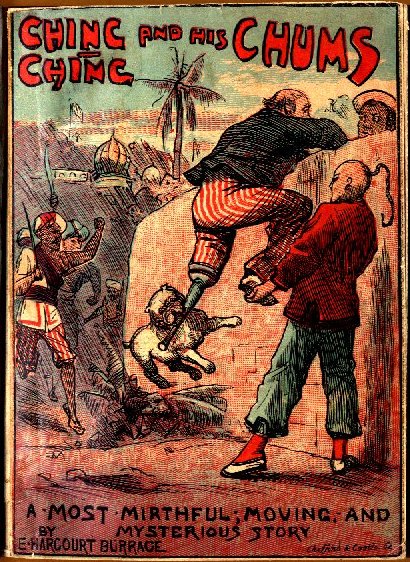

| [4] Ching-Ching and his Chums, cover |

The paper ran in short volumes – Volume I finished with no. 12, Volume II ended with no. 24, etc. With no. 27, the subtitle changed again, rather ungrammatically, to ‘A Thorough Good Journal for the Boys.’ In January 1889 it was announced that the paper was now being published every Wednesday, although it still carried the Saturday date. In March 1889, another announcement stated that the publication day would alter to Monday.

|

| [5] Young Ching-Ching (A Worthy Son of a Worthy Sire) |

|

| [6] |

On 6 December 1890, with no. 128, and with no prior announcement, publication was taken over by the “Best for Boys” Publishing Company, operating out of 17 Gough Square, Fleet Street.

The “Best for Boys” Publishing Company Limited had been incorporated on 28 November 1890 (the papers relating to its incorporation are held at the National Archives in London). Rather oddly, perhaps, William Lucas was not involved, unless he was retained as an employee. The new company, which had share capital of £2,500, divided into 1,500 ordinary shares of £1 each and 100 founders’ shares of £10 each, was founded by seven shareholders headed by Harry Bye, a printer from Wimbledon (who went on to become the Managing Director of the printers Sully & Ford). The other founders were Edwin Harcourt Burrage, Tom Joseph Hartshorn (a solicitor), William Bacon (a stationer), Frederick W. Eaton (a merchant’s clerk), Francis W. Watkins (a cashier), and Frederick Warren (a solicitor). They were subsequently joined by two other shareholders – John E. Strong (a printer), and Strong and Thornbury (paper merchants).

|

| [7] |

The said E. Harcourt Burrage for the consideration herein

appearing hereby agrees to and with the said Tom Joseph

Hartshorn that he will for the space of ten years from the

date hereof write or at his own expense provide the whole

of the literary matter for the future editions of the said serial

publications and that he will not for the same period write

for any other serial or publication of the same class or publish

any tales for boys or literary work otherwise than upon the

account of and through the Company so to be registered.

The said E. Harcourt Burrage shall be a Director of the said

Company and shall edit the said publications. As consideration

for the above he shall be entitled to a weekly salary of six

pounds. The said Harry Bye shall also be a Director of the

said Company and shall be the publisher and superintend the

publishing and bringing out of the said publications and so

long as he shall be such publisher be entitled to a salary of

104 pounds per annum payable weekly.

The “said publications” referred to above were later recorded as being Best for

Boys and Ching-Ching’s Own, suggesting, presumably erroneously, that

these were two separate publications.

|

| [8] |

|

| [9] Daring Ching-Ching; or, the Mysterious Cruise of the Swallow, 18 Nos., “Best for Boys” Publishing Company |

|

| [10] The Wild Adventures of Jam Josser & Eddard Cutten at Home and Abroad, No. 1, by E. Harcourt Burrage, “Best for Boys” Publishing Company |

The publishing company survived, presumably still selling its stock of complete volumes, for a further couple of years. The last Return of Shareholders was made on 31 December 1898, revealing just nine shareholders. Following the absence of a Return the following year, the Registrar of Companies wrote letters in August and September 1900, asking if it was still in business, but these were returned undelivered. Finally, the company was warned in April 1901 that it would be struck off the Companies Register if it failed to respond, but this letter was also returned undelivered. Accordingly, the “Best for Boys” Publishing Company Limited was dissolved by the Registrar via a notice in the London Gazette on 23 July 1901.

In the meantime, T.H. Roberts had launched his own contribution to the Ching-Ching industry with Ching-Ching Yarns, a 68-page pocket-sized weekly which ran for just 12 numbers between April and June 1893. Five years later he and Lucas launched Boys’ Stories of Adventure and Daring, another pocket-sized weekly, priced at a halfpence and an attempt to muscle in on the market in cheaper papers which was becoming dominated by Alfred Harmsworth. In the event, it survived for less than a year, coming to an end in January 1899 after 44 numbers.

|

| [11] |

For his part, Edwin Harcourt Burrage appears to have gone outside the terms of his agreement with the “Best for Boys” Publishing Company when he wrote what turned out to be two of his most popular school serials, The Island School and The Lambs of Littlecote, for the Aldine Publishing Company in 1894-95. After 1900, Burrage wrote more or less exclusively for the Amalgamated Press. Having moved to Redhill in Surrey, he spent several years on the local council and was very active in local affairs. However, his later years were not without financial difficulty, and in 1904 he was obliged to apply to the Royal Literary Fund (a long-established charitable fund set up to help authors in temporary dire straits) for assistance, after ill-health meant he had to stop writing, while he had no savings with which to support his wife and seven children. He was awarded a grant of £50. He died twelve years later, on 5 March 1916.

|

| [12] The Best for Boys Library listings |

Ching-Ching’s Own

Published by W. Lucas

23 June 1888 - 15 March 1890 (91 numbers)

became

Best for Boys – Ching-Ching’s Own

Published by W. Lucas

22 March 1890 - 20 September 1890 (27 numbers)

New Series:

27 September 1890 - 29 November 1890 (10 numbers)

Taken over by “Best for Boys” Publishing Company

6 December 1890 - 23 April 1892 (73 numbers)

became

Best for Merry Boys – Ching-Ching’s Own

Published by “Best for Boys” Publishing Company

30 April 1892 - 17 June 1893 (60 numbers)

replaced with

Bits for Boys

| |

| [13] |

[Note] E. Harcourt Burrage introduced Ching-Ching in Handsome Harry, a serial in the Boys’ Standard, No. 20, March 18, 1876. It was later published in penny numbers as Handsome Harry of the Fighting Belvedere by Hogarth House in 28 parts in the 1880s. Throughout I have used Ching-Ching with a dash rather than Ching Ching, following the lead of its originator E. Harcourt Burrage in the original texts.

Thanks to Nick Harrison Roberts for the photograph of his grandfather Thomas Harrison Roberts

It seems my great-grandfather won a cup with "Ching Ching's Own Society" written on the side. Trivia contest? Any ideas on this one?

ReplyDelete