Charles Henry Ross, creator of Ally Sloper, was born somewhere in London in 1835, the son of Charles Ross, “a veteran” of the Times Parliamentary staff at the House of Commons, and the nephew of Sir William Ross, R. A., who painted several portraits of Queen Victoria and members of the Royal Family. Without actual feet on the ground it’s difficult to trace CHR’s actual birth date and family members since the earliest census records date from only 1841.

The grandfather of Charles Henry Ross (referred to mostly as CHR from here on) was William Ross, born in Scotland in 1765. William was a boyhood chum of the caricaturist Isaac Cruikshank, His parents were both miniature painters. William Ross, his younger brother Hugh Ross (1800-1873), and his sister Magdalena Ross (1802-1874), all became successful miniature painters. William Ross senior also taught drawing.

Hugh Ross exhibited at the Royal Academy 1814-1845 and was awarded several prizes by the Society of Arts. William Ross married Maria Smith, born 1766, who was the sister of Anker Smith the celebrated engraver. Maria exhibited portraits and historical subjects at the Royal Academy between 1791 and 1814.

On her mother’s side she was niece to John Hoole, the translator of “Ariosto.” CHR never knew his grandmother; Maria Ross died in Charlotte Street, Fitzroy Square, on Mar 20 1836, the year after he was born. Grandfather William Ross died at Fitzroy Square in 1850 age 78.

I can’t be too sure exactly how many children William and Maria bore together, the records are not available, but it seems that the oldest child was William, the famous painter uncle who was knighted by Queen Victoria. Sir William Charles Ross, RA was probably born at Tain, Scotland, (although one source claims it was at Milbank Row, Westminster) on 3 Jun 1794. He was a child prodigy whose art career was mentored by his uncle, Anker Smith. He was knighted in 1842 and died unmarried on 20 Jan 1860 at Fitzroy Square, London. One brother, John Ross, was mentioned in his will but has not been traced.

Thomasina Ross was the next in line; she was born in 1795 in Scotland. Thomasina worked as a translator for Bentley’s publishing firm, and contributed to various popular periodicals of the time including Household Words. She died at Sunderland in 1875.

The Ross family moved to London sometime in this period, eventually taking up residence in Charlotte Street, Fitzroy Square, home to a variety of London artists. CHR’s father Charles Ross was born in 1801 in St. Clements, Middlesex. Charles Ross career as a reporter began in 1818, the day Queen Charlotte died, when he attended a meeting at the Crown and Anchor, Strand, held to select a candidate for Westminster. He traveled round the British Isles covering radical meetings for the Times and then entered the parliamentary gallery the day of George III’s death, 29 Jan 1820. Charles occupied the rest of his life employed as the chief of the Times parliamentary staff.

When Charles Dickens was a parliamentary reporter he used to enjoy punch and cigars on Saturday evenings with Charles Ross senior and other reporters of their acquaintance. Ross supplied Dickens with a statistical magazine of juvenile delinquency at the time he was writing Oliver Twist. Charles Ross was still living at the time of the 1881 census at 3, Oakfield St., Kensington, a widower, with his single sister Georgina Ross, a cook, and a housemaid.

Charles Ross sister Georgina Ross, the last child I found, was born in 1803 in Middlesex. Georgina was apparently a writer as well since Charles Ross Jr. recalled that CHR was the nephew of two “well-known” aunts who were writers. Georgina may have been the popular writer “Mrs. Ross,” who penned domestic stories for the Minerva Press featuring old maids, bachelors and governesses. The time period is correct. From census information it seems Georgina never married.

There was a story passed down in the Ross family that Charles Dickens had been a great admirer of Georgina and had once been engaged to her. Her father William Ross was supposed to have thought Dickens a “dissolute young man” and broke off the engagement. There was a 3rd sister, Janet Ross, a miniaturist, who married Dickens’s uncle Edward Barrow.

The Ross family proved remarkably adept at avoiding census workers so that I have been unable to discover with certainty the name of CHR’s mother. However in the 1871 census we find a possibility. Charles Ross, aged 70 (born around 1801), can be found living at 50 Brompton Square, Chelsea, described as a writer of “General Literature” married to Anne H. Ross, aged 63, and a servant. Anne was born in Hayfield, Derbyshire. No maiden name is given and with an abundance of Charles Ross’s to be found in the records there were no doubt others of that name involved in the writing trade.

CHR, the future creator of Ally Sloper, was strongly influenced by the works of Charles Dickens and his illustrators. He would recall in 1882 that “When quite a little boy pictures had a strong fascination for me -- “PHIZ’S” pictures above all. How many hundreds of times have I turned over the dear old books and followed my loved heroes’ and heroines’ adventures by his pictures alone! For the books were read aloud to me before I could read.” His writing shows that he was also fond of disreputable literature in the form of G. W. M. Reynolds’s notorious fictions, The Mysteries of London and Robert Macaire in England.

CHR’s grandfather William was a boyhood friend of Isaac Cruickshank, the father of artist George Cruickshank. Isaac spent his boyhood in Edinburgh, Scotland. When Isaac moved to London, he lived in a house at Salisbury Square, where George was born and raised, within spitting distance of the printers and booksellers of the area. Charles Ross would recall that he saw “a good deal of George Cruikshank in 1850, when he was painting his picture of “Disturbing the Congregation” (I used to take him rough attempts at comic drawings, and he kindly gave me very valuable hints), he was a vigorous energetic gentleman, with remarkable bright piercing eyes.”

Cruikshank showed the same great kindness in criticizing the maiden drawings of young George Augustus Sala before he began drawing woodcuts for The Man in the Moon, a rival of Punch, Edward Lloyd’s penny “bloods” and police sheets. Sala remembered that Cruikshank “kept me with him more than two hours minutely examining my drawings, pointing out their defects, showing (with a little curved gold pencil) how the faults might be remedied…” Sala was still lingering, trembling on the doorstep, when Cruikshank called him back for a final word of advice: “It’s a very precarious profession and if you mean to do anything you’ll have to work much harder than ever the coal-heavers do, down Durham Yard.”

Charles Henry Ross, pretending to write as Ally Sloper in Ally Sloper’s

Guide to the Paris Exhibition (1878) describes a visit to the tobacconist shop

full of penny serials. The titles are real and accurate, possibly real memories of the boyhood reading of C. H. Ross.

“…I did not go there for snuff or tobacco, but for the penny numbers of

exciting serials, which the proprietor also sold…the greatest attraction lay in

the illustrations to the penny serials, changed every week when the new serial

came out, the last published picture if possible exceeding in thrilling

incident that which had gone before. How well I remember and how I cherish the

names of those stories! There were “The Black Monk; or, the Secret of the Grey

Turret,” and “Agnes Primrose; or, the Wreck of the Heart,” and “Ada the

Betrayed, or, the Murder at the Old Smithy,” and “Alice Home, or, the Revenge

of the Blighted One,” and “Blanche Langdale; or, the Outlaw’s Bride,” and “Paul

the Reckless; or, the Fugitive’s Doom,” and “The Maniac Father; or, the Victim of

Seduction,” and “Varney the Vampire; or, the Feast of Blood.”

CHR did not strongly apply himself to the study of art, it seems to have been more of a hobby with him. Following in his father’s footsteps CHR entered the reporters' gallery of the House of Commons, and then, in 1860, took dull employment as a second class clerk in the offices of the Accountant General of the Navy. He used his downtime for writing and doodling, concentrating on selling his wares to the popular penny press.

One of his contemporaries among penny dreadful authors, Vane Ireton St. John, was a clerk at the Inland Revenue from 1858-1867. Drama critic Henry George Hibbert recalled many dramatists, comic journalists and penny-a-liners moonlighting while working as clerks for the civil service. When the Admiralty began staff reduction in 1869 CHR gladly retired on a pension, turning full-time to the perilous life of a penny-a-liner. He recalled his early efforts in an “Only Jones” column of 23 Mar 1887, in Judy, the comic journal he edited at the time.

“About twenty-seven years ago, a certain slim, eager, hatchet-faced young man, in the department of the Accountant General of the Navy at Somerset House, was wont to employ what he called his leisure hours in writing -- what since have been called “Penny Dreadfuls.” They might not all of them have been so very dreadful, and it was rather fun writing them, though there were a great deal too many words to a line, and lines to a column, and columns to a number, bringing the scribe, when the work was done, none too big a handful of shillings. Some of these same stories had surprisingly large sales, and some publishers, still well and hearty, and some others, who have gone where good publishers go, did not do badly; and I, the scribe, and Ernest Warren, one of my co-partners, did not grumble much generally.”

Ross son described him as a “thorough bohemian.” The London bohemian of the sixties and seventies was the result of the merging of Henri Murger’s French bohemian with the “Corinthians” of the days of Tom and Jerry. The bohemians of London haunted Fleet Street as wood-cut artists, theatrical caricaturists, playwrights, and penny-a-liners. When in funds they dressed well, smoked fine cigars, drank, gambled, and whored their way from tavern to tavern throughout the metropolis. Suffering from alcoholism, low on funds, they sold their clothes in pawn shops and dunned former acquaintances on the streets. They were regarded as “disorderly, dirty, and dissipated. A chronic atrophy of the purse was another symptom of the disease…”

CHR, contrary to the stereotypical image of the penny-a-liner, kept his production of penny press ephemera as a sideline to his real job as a clerk at Somerset House, just a short walk from Brydges-street, Covent Garden, home to the offices of the United Kingdom Press. The United Kingdom Press, of 28, Brydges-street, Strand, faced the Drury Lane Theatre, which backed onto Drury Lane. There were numerous taverns in the district which catered to artists, writers and dramatic people, among them the famous “Whistling Oyster,” in Vinegar Yard.

In 1860 the unknown proprietors of UKP began publishing sensational romances in weekly penny numbers. From 26 November 1859, to 25 August 1860, the first ‘sensation’ novel, Wilkie Collins’ The Woman in White, was being issued serially in Dickens's All the Year Round. The success of The Woman in White did not go unnoticed by the proprietors of the UKP. Their first publication was The Woman with the Yellow Hair, a Romance of Good and Bad Society, which went on sale July 15, 1860, in penny weekly and sixpenny monthly parts. The second penny part was presented gratis with purchase of No. 1. The serial ran 25 numbers to about Mar 1861. The last number was composed of only 2 pages as opposed to the usual eight, to a total of 194 pages.

The Woman with the Yellow Hair was dedicated to “Her Most Gracious Majesty Lais One of the Queens of “Bohemia.” The “History of a Sister” followed the night-time adventures of a drunk and dissipated group of fast young men in the Haymarket and in private bordellos throughout London. A later “new and improved edition, carefully revised and in some places entirely re-written, with a sequel of six extra numbers,” was credited to author “George Savage.”

The Serpent on the Hearth, a Mystery of the New Divorce Court was next. The Serpent on the Hearth was advertised 8 July 1860 and published 16 July 1860. The anonymously written serial finished in April 1861 on the 27th weekly number.

The advertising blurb for The Serpent on the Hearth read: “The extraordinary narrative now presented to the public under the above name will disclose some of the most startling and singular circumstances that have yet been published. The work being written by a gentleman moving in the highest circles of society, and one who has been personally concerned in many of the incidents about to be related.”

The third penny dreadful from United Kingdom Press was Charley Wag, the New Jack Sheppard, a New and Intensely Exciting Real Life Romance illustrated By Robert Prowse. It was published in penny numbers and monthly parts with green covers. The green may have been a nod to Charles Dickens who used green on his covers to identify them to readers at the newsstands.

The advertisement observes: “In this work, for which the author has been employed almost night and day for the last two years collecting the necessary materials, will be found the most graphic and reliable pictures of hitherto unknown phases of the dark side of London Life, rendered in stern, truthful language by one who has studied in its blackest enormity the career of secret crime.”

Charley Wag was announced 11 Nov 1860 and began publishing 19 Nov 1860. The penny dreadful was a success running to 72 numbers, finishing approximately May 1862. Charley Wag, The New Jack Sheppard, by George Savage, author of “The Woman With the Yellow Hair,” & “Somebody Else’s Wife,” was re-issued in 32 sixteen page penny numbers by George Vickers , Angel-court, Strand on April 2 1865, and again (possibly concurrently, the date is usually given as 1865 but I could not find this advertised in Reynolds’s Newspaper) by publisher William Grant.

A popular melodrama based on Charley Wag was staged almost immediately at the Britannia Theatre, on December 16, 1860, followed by a version at the City of London written by Nelson Lee. Mr. Charles Dickens representative put a stop to an attempted staging of A Message from the Sea, by the proprietors of the Britannia theatre, advertised for January 7, 1861.

“The drama of Charley Wag was substituted, the audience bearing the disappointment with patience.” The identity of the author would remain hidden seventeen years until 22 April 1877 when a WANTED ad appeared in the Illustrated Police News which revealed the author of Charley Wag (misspelled Wagg,) the New Jack Sheppard to be Charles Henry Ross. Co-incidentally just below Roberts want-ad was an advertisement for John Dicks Boy’s Herald featuring the serial Runaway Jack; or, the Fool of the Family, “by the eminent novelist Charles H. Ross.”

A copy each of the undermentioned works, illustrated royal 8vo.:-

“CHARLEY WAGG,” by Charles H. Ross.

“THE WOMAN WITH THE YELLOW HAIR.”

State lowest price for a perfect (soiled copies not objected to) copy of each to T. H. Roberts and Co., 42 Essex-street, Srand, London, W.C.

No author appeared on the penny parts issues but the bound volume of Woman with the Yellow Hair published in 1861 credits the novel to “the author of ‘Charley Wag.’” The outing of the author probably went un-noticed by most judging by the later authorial attribution of Charley Wag to a diverse crowd of people: George Augustus Sala, John Wilson Ross, George Savage, Edward Ellis and Harry Hazleton.

‘Savage’ and ‘Ellis’ were pseudonyms of CHR’s and the only Hazleton who had anything to do with the title was Frederick Hazleton who wrote a dramatic adaptation of Charley Wag for the stage of the Bower Saloon, a penny gaff in Lambeth. The Rosicrucian author Edward Arthur Waite mentioned “the general repute which has fathered Charley Wag upon him (Ross)” and hinted another PD, The Mysteries of Marlborough House, may have been “improbably made up by Charles H. Ross, who is credited with Charley Wag and The Woman with the Yellow Hair.”

A letter from Waite in the ONO collection dated April 13, 1915, said “There is no certainty as to the authorship of any of the things which you mention, but G. A. Sala was not the writer of “Charley Wag.” Probably it may have been by C. H. Ross.”

On 2 Jan 1878, a faux letter from ‘John Smith’ appeared in Judy, proposing a serial to be titled Untamed Tom, the Terror of Tooting; or, the Boy Buccaneers of Bloomsbury Square. The serial was probably written by CHR or Ernest Warren, which makes the quote below quite plausible as the truth of the ‘business.’

“When I incidentally mention the fact that I am the author of all the Highwaymen Stories worth alluding to during the last twenty years, and was the originator of the Boy Burglar business, in penny numbers, you will see I am the right man.”

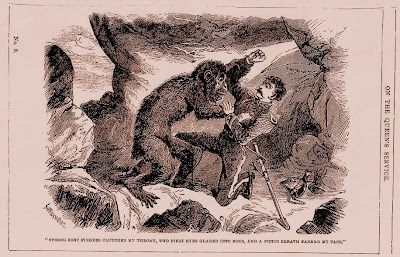

The hero of Charley Wag, the New Jack Sheppard, was a boy burglar and unrepentant murderer. Charley escaped the gallows to be revealed as the heir to a dukedom, and ended up pardoned by the authorities. Charley Wag was the Ur-text of the boys penny dreadful so notorious to the press during the sixties. The early bloods had featured a boy hero in Jack Sheppard but the targeted audience was the adult reader. Boys (and women) certainly purchased bloods but Charley Wag opened up a new market for penny literature featuring boy pirates, boy burglars and boy highwaymen. The language of Charley Wag was breezy, and the situations were sexual, violent and distinctly shocking to the establishment. Ross often talked directly to the reader in a sly, winking, salacious manner: “I have a hangman to introduce to you.”

E. Latham quotes from the opening of an original copy of Charley Wag; “A few extracts will be interesting, either for the purposes of comparison or taken by themselves. Book I. is entitled ‘Childhood in the Gutter;’ the first chapter is headed, ‘All but Murder,’ and begins;

“A woman ran wildly down one of the several steep flights of steps leading from Hungerford Market to the quay below, and creeping along upon the slippery stonework overhanging the water, paused for a moment at the extreme point, cast one fearful, shuddering glance around, and FLUNG HER CHILD INTO THE RIVER. The rain was lashing heavily against the window-panes, and the wind sweeping in fierce and fitful gusts along the deserted streets above, while every now and then a streak of livid lightning rent the air, followed by deafening peals of thunder --… she was young and almost beautiful, but deadly pale ; her hair --... Her flashing eyes, set teeth, and knitted brows bespoke her courage and determination, and her DEADLY PURPOSE. She tore the sleeping babe which a moment since had nestled at her breast, from its warm shelter beneath her thick, plaid shawl, raised it high in the air, to give her the more power, and flung it fiercely from her into the black and sluggish waters gurgling at her feet. “Thus perishes the record of my sin and folly.” It was more a murmured than a spoken thought, for her blanched lips scarce gave utterance to any sound ; but had it been instead the loudest shriek, the raging tempest would have drowned her cry in its boisterous fury --... No one had seen her, no one followed her. The darkness hid her retreating form, and Heaven alone was witness to her crime. The would-be murderess fled away, careful alone of her own safety, heeding not how fared the little living bundle the dark waters swept along towards death. What hope was there for it? What guardian angel came to rescue it? None other than TODDLEBOY.”

Well, the child is taken to a public-house, ‘The Drinking Fish,’ frequented by Mr. Toddleboy, and under the care of the landlady revives; and the author remarks:

“Of course you know very well, gentle Reader, as well as I do myself, that I never intended the baby to die, or else what good would there have been in rescuing it and intruding it upon your polite consideration ? No -- to ease your suspense -- supposing you feel any (and if you are a very young reader, I don’t know that you may not after all), I may as well tell you that in an hour’s time IT WAS ALIVE AND KICKING.”

On December 18, 1867, seven years after the appearance of Charley Wag, a captioned comic page appeared in Judy; or, The London Serio-comic Journal, boldly signed 3 times : C. H. Ross, C H R and C H R again. The title was “Tommy Toddleboy’s Tail Coat.” Note that Mr. Toddleboy was the man who rescued baby Charley Wag from drowning in the Thames.

As mentioned earlier Ross had a collaborator in Ernest Warren, who probably co-authored Ross’ UKP parts. Ross recalled that in “October, 1867, I proposed that he and I should -- after together we had written deeds of daring, breathless ‘scapes, and suchlike --- write together a comic serial story for this journal, (Judy) and -- it may seem odd to some who read -- that when he and I, years afterwards, came to talk the matter over, we both confessed, that we had no recollection, and could come to no conclusion, as to which part of each chapter one or the other wrote.”

Ernest Warren met Ross when both were working for the Civil Service. Warren latterly was employed as London correspondent for the New York Dramatic News. In addition to his work on Judy he also wrote for the rival Fun. He authored a novel titled Four Flirts and the plays Borrowed, Antoinette Rigand, and Modern Wives. Warren, “a man beloved by all who came in contact with him, “died in March 1887. Ross wrote “last Tuesday, the 16th, one of the darkest, coldest, most miserable days I ever remember, he and hope lay buried beneath the drifting snow in the Richmond churchyard, where you may find his grave.”

Ernest Warren, known as “Uncle Inkpen” round the Judy offices, “badly scarred by an illness in Jamaica,” was probably not alone in assisting Ross on penny serials. Another author who may have worked with CHR on his penny dreadful work was Philip Richards. Ross later collaborated with ‘Quentin’ Richards on a serial for Boys of England called Philip’s Perils by Land and Sea. ‘Quentin’ Richards was probably a pen-name for Phillip Richards, an author who continued the Jack Harkaway adventures for Edwin Brett’s Boys of England story paper when Bracebridge Hemyng moved with his creation to New York.

Steve Holland noted that “Henry Richards, his father, was a printer. The family was living at 1 Exeter Change in 1851 at which time Henry's elder brothers Henry and Mark were also printers (the latter an apprentice). But what I find most interesting is in the 1861 census: Philip is then an 18-year-old clerk living at 33 Cranbourne Street with his widowed mother and, at the same address is another clerk, a 26-year-old named Charles H. Ross.”

In 1861 one Charles H. Ross, a clerk, was married to a woman named Constance, born in 1836, and his birthplace is given as Shalford, Essex. There is one mysterious fly in the ointment however, the 1871 census records, which record a Charles H. Ross aged 35 (born in London), and described as an author. He is married to Mary A. J., born circa 1842.

The address was a lodging house at 35 Newman Street, Marylebone. If this is the right person in both censuses then it looks like CHR had two wives within 10 years, Constance Ross and Mary A. J. Ross. Or it could be that the two Charles H. Ross were different people. CHR could not be traced in the 1881 census. CHR’s last wife was Isabella Emilie de Tessier, who drew the Ally Sloper cartoons for Judy as Marie Duval. The future bride was 13 years old in 1861 and lived at 52 New Church Street, Marylebone, with her parents, Joseph and Adale. She was born in Marleybone, London in 1847.

Ross and Phillip Richards must have been acquainted in 1861 when Ross was writing penny numbers about Charley Wag for the United Kingdom Press and it is not unlikely that along with Ernest Warren, Richards was employed by Ross as a “pocket hack.”In addition to churning out copy for the United Kingdom Press, in 1860 Ross edited two annuals for the Tinsley Brothers, and wrote a novel called The Great Gun; his shameful frauds and heartless impostures, an eccentric biography, by Boswell Butt, Esq., for Ward & Lock. The Great Gun featured an Ally Sloper prototype as the hero.

As Ross recalled: “I cannot tell you what it was that suggested Ally, but about 1860 I wrote a book of his adventures for Ward & Lock, only then I called him “the Great Gun.” These were afterwards published as The Ups and Downs of Ally Sloper. Previous to this I introduced the character into a romance I wrote called Dead Acres.” Ross may have mistaken the date -- all surviving library copies are dated 1865 or circa 1865.

The Ups and Downs of Ally Sloper some humiliating confessions was written and illustrated by C. H. Ross and published by the “Judy” Office in 1881. I’m unable to trace Dead Acres but he may be referring to a serial called In Search of a Wife. Ross wrote two serials for Reynolds’s Miscellany using his real name, The Dream of Fate, a Christmas Story (December 28, 1861) and In Search of a Wife a Tale of the Day (January 25, 1862). In Search of a Wife introduced an unsavory character named ’Arry Sloper, the “jolliest of jolly good fellows,” a popular comic singer of the day.

“Everybody knew ‘Arry. He was famous in Five Dials, and all Mounseer’s quarter rang with his praises. His portrait hung in the windows of all the fashionable pork butchers and tripe sellers, and behind the bars of several other public-houses, besides that of the great Potts, where hung one in a very handsome frame, a proof print, rendered more valuable by the inimitable ‘Arry’s autograph (with a blot) in the corner.”

He did, however, have a dark side;

“He was, besides being the jolliest dog alive, the laziest, most dissolute, and most drunken of scamps. All his life he had hung about the bars of public-houses, and all his best days he had so wasted. From his cradle upwards he had been a vagabond.

He had been a bad son and was a bad husband; he had beaten his wife and deserted her; he was like the generality of your jovial boon companions -- as surly a dog as ever had a bone to growl over, when at home with an empty cupboard and a sick wife.”

I stumbled across another pseudonym used by CHR while reading a penny dreadful called Fanny White and her Friend Jack Rawlings, a Romance of a Young Lady Thief and a Boy Burglar, including their Artful Dodges, their Struggles and Adventures; Prisons and Prison-breakings, their Ups and Downs; and their Tricks upon Travellers, Etc., Etc. by The Author Of “Charley Wag,” published by George Vickers on August 2, 1863.

Following a scene where Fanny addresses a religious society with a sex talk followed by an erotic fandango, the author of Fanny White states in the text on page 153;

“Those who kindly followed the fortunes of Master Charley Wag, a hero of mine who made a very successful debut some time ago in society, and of pretty Mrs. Ruth, the female spy and betrayer, will allow, I think, that I have somewhat freely exposed religious hypocrites. In Charley’s life you had a show-up of the “shepherds.” In Ruth’s adventures you had some rather singular details respecting London nunneries.”

“Ruth” was Ruth the Betrayer; or, The Female Spy by Edward Ellis (the author of “Charley Wag”) published by John Dicks, No. 1 appearing February 8, 1862. The Halfpenny Gazette, whose proprietors were G. W. M. Reynolds and John Dicks, ran a serial called The Felon’s Daughter; or, Pamela’s Perils: a Romance of London, from the Palace to the Prison, by G. W. Armitage on March 15, 1862 and The Daughter of Midnight; or, Mysteries of London Life, by the author of “Ruth the Betrayer; or, The Female Spy” commenced with No. 21, July 25, 1863.

When The Felon’s Daughter was published in penny parts by John Dicks the title-page of the bound volume stated that it was “by the author of “Daughter of Midnight.” Thus “Edward Ellis,” “G. W. Armitage,” and “George Savage” were all pseudonyms used by Charles Henry Ross and his collaborators while writing penny dreadfuls.

Likewise the bound volume of The Buccaneers published by John Dicks identified the author as “Edward Ellis,” which allows us to connect numerous anonymous serials in Reynolds’s Miscellany to CHR. The Buccaneers; or, the Hidden Treasure, appeared in Volume 34, No. 877, April 1, 1865. Following the title chains we can connect The King’s Highway. A Romance of The Road 100 Years Ago by The Author of “The Buccaneers,” A White Face and a Black Mask by the author of “The Buccaneers,” A London Mystery by the author of “The Kings Highway,” and last The Clock-Chamber by the author of “A London Mystery,” to “Edward Ellis,” pseudonym of CHR. The Clock Chamber began 18 May 1867 and Reynolds’s Miscellany came to an end with no. 1087 on 19 Jun 1869.

Ross produced many humorous books during the sixties for Dean & Son, George Goody, John & Robert Maxwell, Ward, Lock & Tyler, and Griffith & Farran. In 1865 Rose Mortimer; or, the Ballet-Girls Revenge being the Romance and Reality of a Pretty Actress’s Life behind the Scenes and before the Curtain, by a Comedian of the TR Drury Lane, was published for the London Romance Co. by the Newsagents Publishing Co. in 25 parts. Montague Summers in his Gothic Bibliography wrote that “a contemporary note in my copy gives the initials of the author as C. H. R.”

Judy; or, the London Serio-comic Journal began publishing 1 May 1867 and lasted until 23 Oct 1907. Ally Sloper F. O. M. (Friend of Man) came into the world on 14 August 1867 in a comic page with the strange title “Some of the Mysteries of Loan and Discount,” written and illustrated by CHR, which introduced Ikey Moses and Ally Sloper. Cartoonist James Brown was to draw several comic pages featuring the Scottish character McNab of that Ilk. Ally Sloper disappeared from the pages of Judy in October 1867 after only five appearances but returned December 1, 1869 and before long was appearing every week, crudely drawn by CHR.

On 1 Feb 1868 The Bookseller noted:

“Mr. C. H. Ross, described as a clerk, residing in Surrey Street, Strand, applied for his order of discharge from debts of £1008. The bankrupt stated that he was in receipt of a salary of £310 a year; he also earned about £120 a year as a writer for the periodical press, but he was in such delicate health that his medical man had forbidden him to further exercise his literary talents. Offered to set aside £50 a year. Ultimately the case went off, on an application for additional accounts.”

In 1869 a staff reduction at the Admiralty office made his clerk’s job redundant, and Ross became editor of Judy in October 1869. About February of 1870, Ross handed the majority of artistic work on Ally Sloper over to “Marie Duval.” At first they were jointly signed by the two artists but eventually only Marie Duval’s signature appeared on the comic pages.

In 5 years Judy had a large amount of used comic wood-engravings stocked away and began re-publishing the blocks in “Shilling Books.” They were hawked in the streets by newsboys, sold in newsstands and at booksellers, and tempted commuters from railway bookstall racks. The first comic reprint publication advertised from “Judy’s” Office was titled Judy’s Christmas Number (18 Dec 1872.) The cost was three pence for a short 20 page collection of cuts and possibly some text.

“Marie Duval” was born Isabelle Emilie Louisa Tessier in Marleybone, London in 1847. Very little information is available on Marie Duval. Her fame rests on her contributions to the Ally Sloper comic pages created by Charles Henry Ross in the comic periodical Judy, and reprinted in a shilling book, Ally Sloper a Moral Lesson, (full title: Some Playful Episodes in the Career of Ally Sloper late of Fleet Street, Timbuctoo, Wagga Wagga, Millbank, and elsewhere with Casual References to Ikey Mo) in November 1873. Ally Sloper a Moral Lesson is often called “the first British comic book.” Duval’s drawing style was as crude and uneducated as that of CHR but she did “draw funny,” and that was enough to ensure the characters continuing popularity.

Duval is usually said to have married Ross circa 1869, probably based on the fact that Duval’s first signed cartoons in Judy appeared in August of 1869. Charles Ross was only a contributor at this point, his long reign as Judy editor did not begin until October of 1869. The original proprietor, a man named Bourne, must have been responsible for employing Marie Duval, who drew Ally Sloper cartoons while pursuing a theatrical career. In 1871 Marie Duval was slandered by the Daily News in connection with a sordid theatrical divorce case.

A Theatrical Divorce Case: Such vs. Such

“It appeared that in the autumn of 1870 the petitioner (then a Miss Harvey) and her mother were living at a place called “The Cedars” at Putney, which was a boarding-house kept by the respondent’s mother. An intimacy sprang up between her and the respondent who lived with his mother there, and they were married in November 1870. The petitioner was at the time 24 and the respondent 19 or 20 years of age. The lady was possessed of some £5000 or £6000, and the respondent was an actor employed at the Holborn and Globe Theatres, and he told his wife that he could make from three to four pounds a week. After the marriage they resided at “The Cedars” as before, for some time, and then they removed to Tredegar-road, Brompton. Very soon after the marriage the respondent exhibited symptoms of irregular habits; he stayed out very late at night and sometimes did not come home at all. He also gave up doing anything to earn a living, and on the petitioner remonstrating with him he struck her on the head with a poker. The blow cut her head and blood poured from the wound. The petitioner’s mother entered the room at the time, but she did not see the blow inflicted, and the petitioner told her that she had accidentally knocked her head against the chimney-piece and cut it.

On the 9th of October, 1871, the respondent, whose theatrical name was Augustus Granville, took his wife to the Globe Theatre to see a rehearsal of “Fal-sae-ap-pa.” He there introduced her to Marie Duval, and on leaving the theatre they went to some wine-rooms, where they met that lady. The petitioner, having seen some familiarities pass between her husband and Miss Duval at the theatre, charged him with it on the way home, when he got into a passion, and told her that he liked her much better than his wife. That night the petitioner refused to stay with her husband, and she never did so afterwards, having separated from him in November following. Besides the act of cruelty already alluded to, the respondent was stated to have struck his wife on other occasions, while he was continually taunting her about Miss Duval. On one occasion when she was ill in bed, in the presence of the doctor who attended her, he took from his pocket a photograph of Miss Duval dressed in male attire, and asked the doctor whether she was not far preferable to his wife, and whether she did not look nice in men’s apparel.

In respect to the adultery, Mrs. Unwin stated that she lived in Nelson-square, Blackfriars-road, and in the summer of 1870 Miss Duval came to lodge in her house. After she did so she was visited by the respondent, who went by the name of Granville and often remained with her all night. In the autumn of 1871 she got so disgusted with their conduct that she had them both turned out of the house. The Court considered that both charges had been proved and pronounced a decree nisi with costs against the respondent.”

Since Marie Duval is described as “Miss” in this article she must have been single at the time (Oct.1870) because the theatrical ads identified actors as “Mr.” and actresses as “Miss” or “Mrs.” In one of the few articles written about Duval, Marie Duval and Ally Sloper by David Kunzle in History Workshop, Spring 1982, the author says that an exhaustive search turned up no marriage records for Ross and Duval. He suggests they may have been married in France. Two other researchers of my acquaintance also drew a blank in tracing marriage records. It remains to be seen whether Marie Duval was the mother or step-mother of Charles Ross, Jnr. She may have been living with CHR in a common-law arrangement although she was living as Mrs. Ross at the time of her death in 1890.

Marie Duval’s relationship with Ross did not begin in 1869. If a marriage took place it would have to have followed 1871 and may have been as late as 1874. Charles Ross, Jnr. was born in 1875 in Clapham (some sources say Battersea), but it’s uncertain if he was the son of Marie Duval or CHR’s previous wife. Junior’s only references to her appeared in his 1922 Chats at “The Cheese” columns in Ally Sloper’s Half-Holiday, where she is only described as “his (Ross) wife.” Duval’s contributions to Judy lasted until 1879 and afterward her name only appears on reprinted material in Ally-Sloper’s half-Holiday.

Charles Ross and Marie Duval were intimately connected with the theatre. On March 20, 1870, “Tom and Jerry; or, Life in London Fifty Years Ago,” was in its third week at the Victoria Theatre, the Oriental Theatre on High Street was triple-featuring “The Lost Son“, “Dick Turpin and Tom King” and “Sweeny Todd“, and at the Royal Surrey Theatre, lessees Charles Pitt and A. C. Shelley announced that on Easter Monday a New and Romantic Drama by Charles Henry Ross (the first from his pen), “CLAM,” would be produced with entirely Novel Scenic Effects, Situations, and a New Company of celebrated Artistes. Also on hand was to be a well trained Corps de Ballet . One of these artistes (not in a leading role) was Marie Duval. The show concluded with “a Comicality, in Two Spasms entitled A Sneaking Regard.” Co-incidentally, just before this, around February, 1870, Ross employed Marie Duval to continue Ally Sloper, presumably from his scripts.

“Clam” was a pronounced success with the public and the press and the “screaming farce” of “A Mesmeric Mystery” was added to the concluding show. Ross, writing in “Judy” as The Only Jones, said of an 1876 play called “Jo” that the “pretty notion of inverted commas was adapted from the “Clam” and ”Misery Joy” of a certain popular author, who shall be nameless.” “Misery Joy” had been written by Ross for John Dicks penny periodical Bow Bells.

By May 1, 1870, while “Clam” was still running another concluding show was produced, a “summer pantomime” by Hubert Jay Morice, Esquire with the title “A Drawing Room Perversion of the Beggars’ Uproar; Not Quite Gay, but Much More Lively“, in a prologue and five scenes ;

Scene 1. - Hounslow Heath as it Might Have Been.

Scene 2. - A School for “Dashing Highwaymen” According to Popular Novelists.

Scene 3. - The Grand Carousal of the Knights of the Road.

Scene 4. - Within Newgate.

Scene 5. - The House Tops - The Feline Serenade - The Escape - The Chase - And the Astounding Denouement, never before attempted, and particularly carefully registered.

The Era commented “In the course of the piece we are to be introduced to the very Black Man, and, what will be far better, more than a hundred very pretty Young Ladys. If that is not attractive we know not what can be.”

The “Perversion” was accompanied by an orchestra and dancers, one of whom was Marie Duval.

By the seventh week it was proclaimed that “hundreds are turned away nightly,” and Paul Bedford Jr., whose father had played and sang the part of “Blueskin” in the original “Jack Sheppard” play starring Mary Keeley as Jack, appeared in the closer - “A Tale of a Wig.“

The ninth week of the Surrey success (June 12, 1870) began with the eminent Tragedian Mr. Fairclough, as Shylock, in “The Merchant of Venice” followed by “Clam”, with “Roars of Laughter at the New Police Scene.”

Duval was also touted in her own squib in the Era that day as;

And one more ominous note was to be found in the Original Correspondence column of the Era for June 12 ;

“CLAM”

To The Editor of the Era.

Sir., An advertisement appeared in your paper last week, in which Mr. A. C. Shelley claimed a share in the Copyright of my drama of Clam. A letter from Mr. Shelley’s solicitor also informs me that Mr. Shelley wrote half my play, a fact I was not aware of until Mr. Shelley writes a piece “all by himself.” I am afraid that the easiest refutation of the latter assertion will be denied me; but I beg to inform you that there is no truth whatever in either statement, and that the insertion of such an advertisement is calculated to impede business, and to do me an injury. To the many thousands of kind friends who have come to see Clam over the water, and have applauded so lustily all through this very hot weather; to those gentlemen of the Press, who have spoken so kindly of my first dramatic attempt; and to my private friends, who have read some other little things in other lines I have done from time to time, I am vain enough to believe a denial unnecessary.

I am, Sir, yours faithfully,

Charles H. Ross.

Surrey Theatre, June 10th, 1870.

Charles Dickens died June 12, 1870, the very day Ross letter was published. Squabbles between actors, dramatists and literary men were largely carried out through newspaper and theatrical columns in those days and Mr. A. C. Shelley was not long in posting a reply.

Dear Sir,- Mr. Chas. H. Ross’s letter hereon, relative to myself, conveys a sneer as little worthy of the gravity of the subject in dispute as it is useless for his defence ; and I cannot, in common politeness, refuse him the reply his composition has provoked. It would have been better had he waited for public notoriety through the medium of Chancery than to have rashly advertised himself through the channel of your Journal. But anger has some claim to indulgence, and railing is usually a relief to the mind. He insinuates I am not able to write a play “all by myself.” The public must judge of his motive. If there is anything in Clam which deserves the name of “genius,” I am happy in acquainting the world that I drew it from the same fountain, and at the same time, that Mr. Ross did, and in equal proportions. He says, “It is calculated to impede business.” But in it he does not tell you that, for several consecutive weeks, I was engaged up to midnight writing the very piece on which he builds his reputation as a Dramatic Author ! I have proofs of my assertion, and at the proper time they shall be forthcoming.

He has appealed to the compassion of your readers; I appeal to their understandings. When I withdrew from the management of the Surrey Theatre, Mr. Ross astounded me. He wrote me a letter, absolutely repudiating my right to share in the proceeds of the drama, and I am consequently compelled to protect myself through the soothing influence of an action at law. He has driven me to measures which it was better I had been spared the pains of commencing. I am the registered proprietor of the drama, and trust this reply has fully satisfied his appetite. I apprehend but little danger from his voracity. Thanking you for your courtesy, usually accorded to Professionals. I am, faithfully yours, ADOLPHUS C. SHELLEY. 16, Brunswick-terrace, Camberwell

The battle in the Correspondence column of the Era was carried on the following week, June 26, 1870.

“Clam”

Sir,- Seeing that Mr. Shelley persists in asserting that he is part author of Clam, will you kindly permit me to supplement my letter which appeared in last week’s Era by a few facts ?

1st. The drama in question was written entirely by myself, unaided by any other person.

2d. My handwriting not being as legible as could be wished, Mr. Shelley, some three or four months ago, undertook to make a fair copy of the drama, which he supposed I had only then recently written.

3d. On receiving back my MS., together with what I expected would be a fair copy, I was annoyed at finding that Mr. Shelley, instead of confining himself to copying, had in several places altered the dialogue, and in others introduced dialogue of his own. It may have been an error of judgement on my part, but, preferring my own composition to his, I immediately restored the drama to the form in which Mr. Shelley had received it from me.

4th. The prompter’s copy was made by the copyist of the Theatre from my MS.

5th. The copy in the Lord Chamberlain’s Office is in my MS., and I hold a letter written to me by Mr. Shelley, undertaking to perform certain services in connection with (I quote his exact words) “your drama Clam.”

6th, and last (which, if Mr. Shelley had been aware of, we should never have heard of him in connection with the authorship of Clam), the drama was written four years ago, and the original MS. bears upon it the annotations, made at the time by my friend Mr. Dominick Murray, who did me the favour to read it, and is now acting the principal character in America.

I am, sir, your obedient servant, Chas. H. Ross.

The same day the Surrey Theatre advertised “This Popular Theatre to LET ON LEASE, with immediate possession. Apply to Messrs. Head and Coode, Solicitors, 29, Mark-lane, E.C.

“Clam” returned July 10, 1870 at Mr. Benjamin O. Conquest's Grecian Theatre, in the City-Road, described as “the Great Surrey Drama of “Clam” by C. H. Ross, Esq.” Piccadilly Peter was played by Miss E. Dorling in place of Mrs. Duval, the entire original cast replaced by the stock company of the Grecian. July 17 “Clam” was reviewed in the Era ;

There is so much smartness and humour in Mr. C. H. Ross’s drama called Clam, it contains such a great abundance and variety of striking situations, and many of the characters in it are so original and diverting…….has met with the same hearty approval throughout the week as that which it secured recently when it was performed at the Surrey.”

“Much laughter was occasioned by the Police-station Scene. The transactions at Dead Man’s-lane excited great interest. The dancing at Cremorne, or rather at the Grecian, as heartily admired, and the entire performance was well received, and occasioned frequent applause.’

The last performance at the Grecian was July 24, 1870, when another letter regarding “Clam” reached the correspondence columns.

“Clam”

Sir, in a recent number of your paper Mr. Ross states that his drama was written some four years since. Now the incidents of the drama are embodied in a tale published in a penny periodical called the London Herald. The opening chapter commenced in No. 330 of that periodical, and the tale was entitled “The White Hand; or, The Jewelled Snake.” It ran through some seventeen or eighteen numbers, one of the principal characters being Clam, and many of the other characters in the tale are also in the drama. The date of publication was December 28, 1867. Yours truly, DIOGENES.

And the last letter on the subject appeared July 31, 1870.

“Clam”

Sir.- Judging from Mr. Shelley’s letter recently published in your Journal, he is evidently unacquainted with the whole of Clam’s history, and being convinced that I have had quite as much to do with the authorship of the piece as he has, perhaps a few words from me may not only enlighten him, but may also be the means of saving him some little trouble.

The main idea of Clam was suggested by my wife, and was fully worked out by Mr. Charles H. Ross and myself nearly five years ago, with a view to its production at Astley’s Theatre, during the season of 1865-6. Mr. T. H. Friend, at the same time Stage-manager, can testify that an outline of the piece was submitted to him by Mrs. Murray, who especially directed his attention to an equestrian scene in Rotten-row and the scene at Cremorne as being likely to suit Mr. E. T. Smith. Now as the piece lately played at the Surrey is in all respects, excepting the introduction of horses, identical with the drama written nearly five years since, I certainly think that Mr. Shelley is labouring under some mistake as to his share of the authorship; and setting aside the little labour bestowed upon the work by my wife and myself, Mr. Ross is the bona fide, and I may say the sole, author of Clam.

Yours, &c., Dominick Murray, New York, July 9, 1870.

The next mention of “Clam” is September 18, 1870, as it tours the Provincial Theatres ;

MR. CHARLES H. ROSS’S Great drama of “CLAM”

Birmingham.- Prince of Wales Theatre, Sept. 17, Six Nights.

Miss Agnes Burdett in her Original and Great Impersonation of Clam

Mr. Augustus Glover as Ephraim Webb

Miss Marie Duvall as Piccadilly Peter

The case of Shelley vs. Ross was finally heard 11 Jun 1871 at Westminster Bail Court. Verdict went to the co-defendant, Charles Henry Ross, the plaintiff failed to establish his joint authorship of the play ‘CLAM.’

Also on July 31, 1870;

Charing-Cross Theatre.- Mr. CHARLES H. ROSS having taken the above Theatre, to OPEN early in October, is at Liberty to receive offers from Amateurs, &c., for the hire of the Theatre in the interim. Applications to be addressed to the MANAGER, at the Theatre.

September 25, 1870 it was announced that the Surrey would re-open under the management of Mr. E. T. Smith showing farce, drama and burlesque, and another squib from the Charing-Cross Theatre said the October opening would have a “New and Original “Realism” by the author of Clam and other Novelties.”

Ross (sharing the authorship credits with one Philip Richards this time) however, was to return to the Surrey, under E. T. Smith, with The New Sensation Drama RUTH ; or, A Poor Girl’s Life in London, on February 18, 1871.

“Miss Marie Duval well enacts the role of Lord Fernfield. She makes a strikingly dapper and elegant young gentleman. Her assumption of the bearing of a lord of the creation, and her affectation of aristocratic ease and frigidity, are accomplished with great cleverness.”

Ellen Clayton recounted how Duval played another boys role in 1874, that of escape artist Jack Sheppard, a role traditionally played by young women.

At Yarmouth “she, as Jack, had to make a desperate escape, climbing up a rope ladder from a boat on to old London Bridge, under a volley of pistol shots from Jonathan Wild, the thief-taker and his myrmidons. The cartridge from one of the pistols struck the actress on the side of the face, thus obliging her to loose her hold. She fell from the ladder, receiving a severe cut on the leg from a piece of iron used to strengthen the scenery. With a great effort she managed to climb the rope once more, and so brought the scene to a close, but the play had to end with this act.” She was stitched up and cast members carried her to the Star Hotel at midnight in a makeshift sedan chair.

In 1870 the comic journal Fun, rival to Punch and Judy, was bought by Dalziell Brothers, the engravers. In 1872 Judy was also taken over by the Dalziel’s and youngest brother Gilbert Dalziel became the conductor. The first issue (1876) of the annual Ally Sloper’s Comic Kalendar reportedly sold 120,000 shilling copies. The Ally Sloper cartoons and character increased in popularity and in 1883 Ross sold his rights in the character to Gilbert Dalziel of Dalziel Brothers, the engravers, who launched Ally Sloper's Half-Holiday on May 3, 1884 for the proprietor W. J. Sinkins.

CHR was author of numerous novels. The Pretty Widow, published in 2 volumes in 1868 by the Tinsley Brothers, was translated and published successfully in Germany and France. A London Romance came out in 3 volumes in 1869, A Private Inquiry (featuring a private detective) in 1870, and Lovely Angelina in 1874.

It has been speculated that CHR used the pseudonym Percival Wolfe for the penny dreadfuls Wild Will; or, The Pirates of the Thames and Red Ralph; or, The Daughter of Night a romance of the road in the days of Dick Turpin, both for the London Romance Company. He has also been tied to Hounslow Heath and its Moonlight Riders, from the same publisher, writing as Julian St. George. He wrote the serials Hush Money, The Doom of the Dancing Master, and Misery Joy for John Dicks Bow Bells. He also edited and conducted various round-robin serials for Bow Bells Christmas numbers.

The last contribution I know of by Ross to appear in JUDY was on July 13, 1887, an illustrated column as THE ONLY JONES, his credit as the editor had already been dropped. He left Judy and launched one final comic journal in 1887, C. H. Ross’s Variety Paper, but after 34 penny weekly issues the publication went under. Marie Duval’s death is registered in Wandsworth, London, in the second quarter of 1890, age 39, (she was actually 42). In the 1891 census CHR is living (as Charles Harry Ross) at 501 Wandsworth Road, Clapham, a widower and author. He has a son, Charles Jnr., aged 16, born in 1875 in Clapham, (other sources say Battersea), who is described as an artist.

CHR collaborated with Frank Wyatt on one final work published by W. J. Sinkins, The Earth Girl, a Weird Legend, in 1893. The story involved a vile woman from the bowels of the earth who ruins men above ground before returning to where she came. Punch called it “Hugoesque” and said the authors wanted, like the Pickwickian Fat Boy, “to make our flesh creep.” On October 12, 1897, Charles Henry Ross, caricaturist, journalist, dramatic and penny dreadful author, died after a long and painful illness. His death was duly noted in the theatrical paper, The Era on October 23, 1897:

Deaths.

ROSS. -- On October 12th, after a long and painful illness, Charles H. Ross, journalist and dramatic author.

The late Mr. C. H. Ross, who died recently after a long and painful illness, soon found actors and entertainers looking to the possibilities of Ally Sloper from the stage and platform point of view. About the time of the first “boom” in Sloper, among the contributors to Judy was an able young humourist, then known as Mr. Grove Palmer, who developed into that smart comedian, Mr. Fred Grove. At the time referred to Mr. Grove Palmer gave some capital little shows at schoolrooms, &c, in the West-end. Ross was always delighted with Palmer’s portrait of Ally. Then Ross fell in with Robert Sweetman, who had done much good work in the provinces, but got the idea that a single-handed show would bring more glory and gain than a part in a piece. Ross superintended the make-up of Sweetman as Sloper, and gave the actor many hints. After Sweetman’s death the Sloper costume and make-up were offered for a mere song. Mr. Ross lived in a picturesque old house in the Wandsworth-road, for years inhabited by Mr. John Jolly Nash.

In the seventies Mr. Ross wrote several plays which were produced at the London and provincial theatres. He was the author of ‘CLAM,’ a drama in three acts produced at the Surrey Theatre, April 16th, 1870; Silence, a drama in four acts produced at the Holburn Theatre, May 6th, 1871; and of The Prisoners At The Bar, operetta, brought out at the Alexandra Theatre, Liverpool, June 17th, 1878. He was also part author of the following pieces:- The pantomime of The Sleeping Beauty, brought out at Covent-garden, Dec. 26th, 1870; Ruth; or, a Poor Girl’s Life in London, first played at the Surrey, Feb. 18th, 1871; Lantern Light, a drama in a prologue and four acts, produced at the Elephant and Castle, Feb. 15th, 1873; and the burlesque The Desperate Adventures of the Baby; or, The Wandering Heir, brought out at the Strand Theatre, Dec. 14th, 1878, in which appeared Miss Lottie Venne, Miss Violet Cameron, and Mons. Marius.

October 30, 1897.

The Late C. H. Ross.

To The Editor of the Era.

Sir,- In enumerating the late C. H. Ross’s pieces, one produced in April, 1872, should not be forgotten, viz, A Rose in the Mire. Those who saw it may remember the vivid scene of Covent-garden Market with its early morning brightness, the “turn out” from Evans’s, and the double-set picture of the wronged heroine making the bridal dress for her rival, who is in the adjoining compartment with her seducer. This piece was a great success, and was followed by Ross’s production of Life. His last dramatic speculation was with a play called A Detective, toured for seventy-nine weeks under the management of

Yours faithfully, JAMES E. THURLOW. Grand Opera House, Belfast, Oct. 26, 1897.

The passing of Charles Henry Ross was ignored by the proprietors of JUDY, in just ten years his significant contribution to comic art and serial literature had been entirely forgotten by the very publication whose popularity was due to his prolific pen.

*Many thanks to Steve Holland, Robert Kirkpatrick, Roger Sabin and Bill Blackbeard.

***