Wednesday, June 14, 2023

A Crowded Life in Comics –

Monday, June 5, 2023

Seven Men Who Draw Funny Pictures

SEVEN MEN WHO DRAW FUNNY

PICTURES—AND LARGE SALARIES

Literary Digest, August 14, 1920, author unknown

DRAWING A FINE PICTURE of Niagara Falls on the starched front of his father's dress shirt and standing up that night to eat his supper marked the first venture into art of Bud Fisher, creator of Mutt and Jeff. Now Mr. Fisher's drawings earn him a quarter of a million a year, he lives in a ten-room apartment on Riverside Drive, New York City, and we are told he is the possessor of a pearl-inlaid ukulele and a German police dog, to say nothing of a yacht and a fine country estate in England. Bud Fisher is one of seven nationally famous comic artists, not one of whom earns less than $25,000 a year, and at least three of whom receive salaries exceeding that of the President of the United States. The others are Rube Goldberg, of "Boob McNutt" fame; Clare Briggs, originator of "Skinnay"; Gene Byrnes, who portrays the antics of "Reglar Fellars"; T. A. (Tad) Dorgan, responsible for "Silk Hat Harry''; Fontaine Fox, who runs the ''Toonerville Trolley''; and George McManus, who lets the world in on "Bringing Up Father."

To Jane Dixon, representing People's Favorite

Magazine (New York), these gentlemen recently related the circumstances of

their entering the cartoonists' profession and how they happened to develop the

comic features which have made them famous. Of Mr. Fisher we learn that he was

connected with the San Francisco Chronicle, covering the races at $15 a week,

when he drew the first of the "Mutt and Jeff" series. He says:

"One evening I came into the office late. My ponies had

all run backward that day and I was feeling low. I sat down, drew a picture of

my own idea of myself, labeled it 'A. Mutt,' and handed it to the night editor.

"'That's a funny-looking bird,' said the N. E. 'Who is

he?'

'"That's me,' I answered, 'A. Mutt.'

"The next day they sent Mutt to cover the races."

The success of A. Mutt was instantaneous. He began picking

winners. His luck was uncanny. It seemed he could not lose. The editor of The

Chronicle once told me race fans used to line up outside the building every

morning for a block or more waiting to grab the first papers off the press for

Mutt's tips.

Came the Reuff scandals in San Francisco. The Chronicle was

bitterly opposed to the policies of the Reuff mayoralty ring. Bud Fisher took

Mutt to visit a local insane asylum. There Mutt found little Jeff, and adopted

him because, as he explained, "Jeff was the only man in the world crazier

than Abe Reuff." The little fellow proved such a hit he was kept in the

picture.

By way of the San Francisco Bulletin Bud Fisher came to New

York, joined The American, moved on to The World. The trail leads upward in

such leaps and bounds it has the effect of making the audience dizzy.

"Salesmanship?" says the leaper. "Sure. Make up

your mind what you are worth and stick to it. Never ask more than you know you

are worth. The other fellow may say you are crazy, but if you prove he is wrong

he will not haggle with you the next time you come to sell your goods."

Today Mutt and Jeff are cashing in to the tune of a quarter of

a million dollars a year. They are harvesting laughs from their cartoons,

moving pictures, "legitimate" shows, and books in cities and

jerkwater junctions of every State in the Union, not to mention Great Britain,

Japan, Mexico, Australia, Canada, Cuba, and France. Even New Zealand joins in

the chorus.

Rube Goldberg told the interviewer that the first picture he

drew that brought results was one of his teacher. He admitted it did not

flatter the lady much, but said the results made him sore for several days.

Goldberg's father decided his son should be a mining engineer and to that end

sent him to the University of California, where the young man drew some

pictures for the college paper. Further:

"When I was graduated I went out into the gold-fields of California to embark upon my career of mining engineer. I suffered through two miserable months, with the drawing urge growing stronger every hour. Finally I packed my kit, went back to San Francisco, and told father he'd have to dig up another mining engineer for the family tree. He was disappointed but agreed to compromise on civil engineering. I was sent to the city hall, where I drew a hundred dollars a month and plans for sewerage systems. One day I dropped into the office of The Chronicle. The editor's son had been a college friend, and the governor was familiar with my work on The Pelican. He agreed to pay me eight dollars a week. I would gladly have worked for nothing.

"The drop from twenty-five per to eight did not sit well

with the home folks. Father gave me up as hopeless. Not until I came in, many

months later, and announced I had been raised to thirty-five dollars a week did

he concede he might have been wrong about the mining stuff.

"From The Chronicle I went to The Bulletin, where the

cartoonist was given a better show. Here I developed a New York bug. The editor

offered me $50 a week to stay put, but it was the big town or nothing. Arrived

in the city of my dreams, I peddled my drawings to every paper. I ended with

The Mail, and there I landed. That was thirteen years ago. I've been on The

Mail the entire stretch. To be successful, a fellow must keep his work moving

along. The minute he stalls the engine popularity begins to slip through his

fingers. And he must get better all the time. Just as good is not good enough.

He must be out to beat his own record."

Clare Briggs went to school at the University of Nebraska,

where General Pershing was his teacher in mathematics, a branch of learning in

which the cartoonist admits he held the cup for remaining longer than anybody

else at the foot of the class.

On one occasion, when the teacher's patience was completely

exhausted, he yelled: "Briggs, sit down. You don't know anything."

After that, says Briggs, there was nothing left for him to do but become a

cartoonist, and on the advice of a friend he went to St. Louis to look for a

job —

"After several

discouraging weeks I tackled The Globe-Democrat. I asked for $15 a week, on the

principle you can't shoot a man for asking. They gave me a ten-spot. You should

have heard my six-dollar friend howl from his perch on The Republic.

"Just as it seemed I was about to make my fortune on a

twenty-five-dollar-a-week shift, and that I could go back home and claim the

girl I was convinced every fellow with a grain of sense was trying to steal

away from me, the half-tone picture came along and kicked the feet from under

newspaper artists. It looked Kke the end of the world then, but it proved to be

exactly the thing we needed. Now we were compelled to use our imaginations, our

inventiveness.

"At the close of the Spanish-American War I was fired. I

had enough left over to make a smoking-car trip to New York. My total fortune

on reaching the big town was 15. For the next two years I lived mostly on

nothing a week, the exception being an occasional comic to The World. The

minute I hit the twenty-five dollar mark I made a flying leap out after the

girl. Under her influence my star began to ascend. I received an offer from the

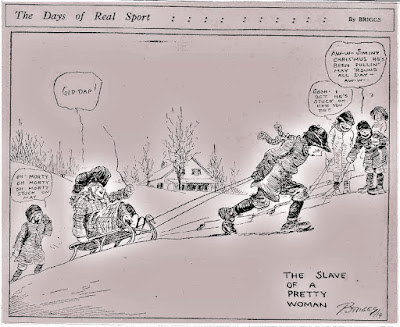

Chicago Herald to draw sport cartoons. It was here I began my kid series, an

idea inspired by the fact Chicago was thoroughly disgusted with the conduct of

its baseball teams. I called my series ‘The Days of Real Sports.’ Skinnay and

the pup brought me back to New York and to The Tribune. A great boy —Skinnay.

He built me a fine home in the country, and the girl from home likes him."

In the picturesque Briggs home. New Rochelle, are three of the

younger generation — a daughter of nineteen, a son of fourteen, and a girl of

two. It is on the strength of the baby that the artist and the girl from home

are collaborating on a new series, ‘What a Baby Thinks About.’ Says father

Briggs: "As it is the finest baby in the world, it ought to be a bang-up

series."

The Briggs house is built from the timbers of an old schooner

reclaimed from a shipyard, because, as the owner explains it, he "hates

anything new and shiny." It is situated on a rocky knoll, with a brook

tumbling along at its base, and is the show place of a section where artistry

and architecture go hand in hand.

There Clare Briggs, who asserts there should be a law passed

permitting a man to change his name at will, plays at being a boy again. He

drops down to the city in his trusty Cadillac long enough to turn out

"When a Feller Needs a Friend," or "Somebody's Always Taking the

Joy Out of Life," or "Ain't It a Grand and Glorious Feehng?"

While in the city he visits his banker to see if the last quarterly ten or

twenty thousand came in on time.

"Dinty Moore," the perpetual source of trouble

between "Maggie" and "Jiggs" in that edifying drama,

"Bringing Up Father," was first seen by George McManus in a show in

St. Louis, where the cartoonist's father was in the theatrical business.

McManus says he liked Dinty the minute he saw him and has been using him in his

cartoons ever since. Of Mr. McManus's career we read:

"Nineteen seemed to me a fairly good age to start on the

trail to fortune. I had saved a little money, and it bothered me. New York was

the place to spread it. I hit the big town and found its possibilities as a

playground had been greatly underestimated. Not until the bank-roll had melted

did I bother about work. I was up against it, but too proud to wire home a

distress signal. On the strength of some half-page series, the Sunday World

gave me a six months' contract.

"My first character of importance was a tramp I called

Panhandle Pete. Then I struck my first real pay streak. I met the girl who has

since become Mrs. McManus. She was the inspiration for the 'Newlyweds,' serving

as the model for the principal character. She went over big. Then came 'Let

George Do It,' for The Evening World. Finally I signed a long contract with The

Journal and American and started 'Bringing Up Father.''

Thomas A. Dorgan, "Tad," was brought up in San

Francisco. His first job was on The Bulletin in that city, where he started at

$3 a week. He fell down on an assignment, was fired, and had to work six months

for nothing before he got back to three per once more. To quote Mr. Dorgan

himself:

"Shortly after I hit the thirty-dollar mark —large money

in those days—I had a letter from a man by the name of Brisbane. He said if I

would come to New York, he would pay me $75 a week. I showed the letter to the

boss's secretary, a young lady wise in the business.

'Forget it,' she said. 'The boys are kidding you.'

"I remember the gang held a heavy conference to decide

whether the letter was a cheater or on the level. They came to the conclusion

there wasn't that much money.

" I wrote to this Mr. Brisbane to find out what made him

think he was one of the Morgans. Back came a note repeating the offer. My

getaway broke all speed records in a town where traveling was never anything

but the fastest. In New York I went to the address given in the letter and met Mr.

Arthur

Brisbane, a power on The American. He offered to sign me for a year at the given figure. If he would only have made it a hundred years I would probably have choked to death in my haste to yell 'Let's go.'"

Fontaine Fox, who operates the "Toonerville

Trolley," came from Louisville. His artistic bent manifested itself, when,

at the early age of seven, he drew a train of four hundred freight cars on the

new parlor wall-paper. Apparently his ability was not appreciated at home, for

he was sent to Indiana University to become a lawyer or doctor. After leaving

school, however,

he became connected with the Chicago Post. Further: He

bethought him of the trick trolley-line which bounced him to and from work back

in Louisville. Might be a good idea to try it out on the city folk. With the

since-famous "Skipper" in charge, he sent the Toonerville trolley on

its daily run through The Post. It carried the ambitious creator straight

through to

success. At the same time he found "Thomas Edison,

Jr.," trying on a discarded derby hat retrieved from an ash-pile in a

vacant lot near his home. The junior Edison's mother caught her dear hopeful

just as he was emerging from the lot, the hat riding well down over his ears.

" I followed the two of them to a barbershop, where the

boy received one close haircut by way of punishment," says Mr. Fox.

"I went home and drew my first kid cartoon. I have always been glad I

followed that indignation meeting to the barbers.

"It took my father a long while to become reconciled to

the absence of a handle at the end of my name. Even now he shakes his head and

allows as how cartooning is a queer way to make a living."

Fate spoiled a perfectly good harness-maker when she made Gene

Byrnes a cartoonist, according to his own version of the case. He says:

" I was booked to follow in my father's footsteps, but I

lost the trail and started a shoe-repairing shop instead. I ran the first

electric repair shop in Brooklyn -' Sole you while you wait.' My next job was

selling a certain bug dispeller, for which I drew down the weighty recompense

of $12 a week, with a promise of $15. One day I was sent to give a practical

demonstration of my wares in a hotel. I couldn't stand the gaff, so I checked

my stock and went to The Evening Telegram. "I had done considerable

drawing for The Brooklyn Times but had given it up as a wrong lead. It took all

my time explaining my 'balloons' to an editor who had charge of the comics

during my stretch. He was the sort of a cuckoo who went to the Winter Garden

and thought Frank Tunney was a tragedian.

"The Telegram editor agreed to give me a try-out. I

turned in a one-panel comic, 'Reglar Fellers," After a while the editor

informed me I would have to come across with something else; he was not running

a seed catalog. The result was ‘It ' s a Great Life If You Don't Weaken.' The

success of this strip encouraged me to try ' Wide-Awake Willie' for The Herald.

You should see them now translating Willie for the Hungarian trade. It hands me

a jolt every time I look at Willie done up in bundles, ready for his overseas

journey. A fellow never knows how far he can go until he starts

traveling."

.png)