1831

by E.M. Sanchez-Saavedra

During the 1830s, New York publishers revolutionized the newspaper business with the introduction of the penny daily. Benjamin Day’s New York Sun was the first, in September 1833. Its motto was, “It Shines For All.” Advances in printing and papermaking had brought the overhead costs down to the point where such an innovation could be profitable, based on sales volume. By 1835, Day was printing thousands of copies the Sun on a rotary steam press. Like the older papers, advertising still accounted for the main operating cash flow, but the new dailies cut across all social strata and soon engaged in furious competition. At first, papers engaged in dubious methods, like the notorious ‘Moon Hoax’ perpetrated by the New York Sun. (For weeks, bug-eyed readers consumed reams of rubbish about lunar creatures, said to be under daily observation by astronomer Sir John Herschel.)

Notwithstanding this scandal, daily papers spread throughout the U.S. Large numbers of working folk and recent immigrants were able to acquire useful information more or less at first hand. The political process grew rowdier but more democratic and cosmopolitan. For a time, Karl Marx was a regular London correspondent for Horace Greeley’s New York Weekly Tribune!

1836

Sensation – of course, crime and scandal sold papers then as now. The peccadilloes of actresses, sensational divorces and items from the police court blotters kept circulation figures up. When war broke out, editors began sending reporters to the front and saw their sales increase accordingly.

Despite the First Amendment, there have been numerous attempts to muzzle the press, from John Adams’ Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798 to Abraham Lincoln’s successful suppression of all Northern papers critical of his administration and the conduct of the war for the Union. Before the war, a number of Abolitionist editors were persecuted by pro-slavery mobs, notably Elijah P. Lovejoy, assassinated in 1837 in Alton, Illinois. During the gangster era of the 1920s and 1930s, several editors and investigative journalists were threatened, beaten up and murdered for their anti-Mob activities.

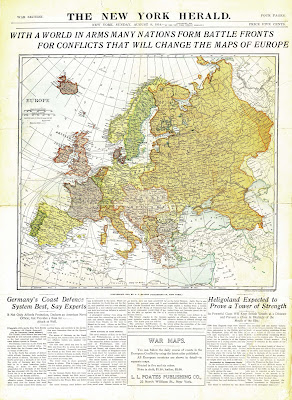

Perhaps the greatest visual difference between modern papers and their ancestors is the dominance of graphics. Cheap publishers of broadsides, ballad sheets, pamphlets and chapbooks had known since the 15th century that an illustration – any illustration – helped sales. James Gordon Bennett’s New York Herald, started in 1835, soon began to trump its competitors by running small front-page illustrations. In June 1845, the entire front page was taken up by a strip illustration purporting to show Andrew Jackson’s funeral procession, the art was by T.W. Strong. This came only three years after the launch of the Illustrated London News, the first fully illustrated weekly news magazine. During the U.S.-Mexican War of 1846-48, and the U.S. Civil War of 1861-65, the Herald printed scores of views and battle maps for its readership. Amidst Federal censorship, the hostility of Union commanders to reporters and the difficulties of travel in wartime, modern journalism got its start as a profession during the Civil War years.

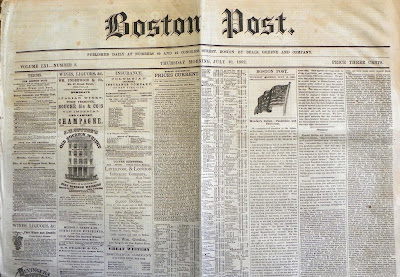

Most dailies were hesitant to add the expense of engraved woodcuts to news stories, although they maintained a large repertoire of ‘stock cuts’ to adorn advertising items. Beginning in the 18th century, classified ads were distinguished by appropriate icons – houses, ships, runaway slaves, cattle, wearing apparel, and later, railroads, steamboats and so forth. By the mid-19th century, prosperous advertisers provided their own illustrations and a typical front page might be adorned with several large commercial cuts in addition to the tiny classified icons. Lincoln’s assassination in 1865 marked a turning point as many papers ran memorial images of the slain leader during the days following his murder.

The principal headline format also underwent major changes, escaping the confines of a single column and blaring across the entire front page in letters an inch and a half high by century’s end. The old ‘inverted pyramid’ headlines, using a series of disjointed statements, were simplified and boiled down into a phrase or two with plenty of ‘oomph.’

Thanks to the rotary press, which used long rolls of paper, an edition of eight-page newspapers could be printed all at once, pausing only to change rolls. Unlike flatbed hand-operated presses, which printed one side of the sheet, the paper passed between two inked semicircular plates in endless succession. Individual issues were automatically sliced off the roll and then folded by hand. Customers received their papers folded but uncut!

Benjamin Robert Haydon’s 1831 genre painting, ‘Waiting for the Times’ [see above] shows a reader in a club room struggling with an uncut issue while a glowering man waits impatiently for him to finish. Many English papers were printed on different paper stock, depending on the class of their subscribers. The Times of London and the Illustrated London News printed editions on the finest grade of snowy white stiff rag paper, which could be ironed perfectly flat by a butler or valet... Other press runs were on cheaper stock, particularly out-of-town and overseas editions. This was partly to save shipping weight.

Benjamin Robert Haydon’s 1831 genre painting, ‘Waiting for the Times’ [see above] shows a reader in a club room struggling with an uncut issue while a glowering man waits impatiently for him to finish. Many English papers were printed on different paper stock, depending on the class of their subscribers. The Times of London and the Illustrated London News printed editions on the finest grade of snowy white stiff rag paper, which could be ironed perfectly flat by a butler or valet... Other press runs were on cheaper stock, particularly out-of-town and overseas editions. This was partly to save shipping weight.

Because the physical processes of typesetting, laying out forms, stereotyping and printing were all labor intensive and time consuming, important news often broke after the paper had been “put to bed,” completed to be printed. Rather than destroy an edition, publishers would print ‘Extras,’ usually hastily typeset, run off quickly on a job press. These could be in the form of broadsides, or crudely reconstructed regular editions, with new columns replacing the originals. Thanks to modern telecommunications, the newspaper Extra is a thing of the past, although a special edition is still possible on rare occasions. After the September 11, 2001 attacks, many papers issued extraordinary supplements and memorial editions.

According to popular myth, the appearance of an Extra in the 19th century, and up through World War II, sent scores of newsboys racing through the streets, hollering “Extra! Extra! Read All About It!” with a snatch of the headline. (After yelling themselves hoarse, the newsboys’ cry reputedly sounded like “Wuxtry! Wuxtry! Reed Allabatit! Japs Bomb Poil Hobbah!”)

According to popular myth, the appearance of an Extra in the 19th century, and up through World War II, sent scores of newsboys racing through the streets, hollering “Extra! Extra! Read All About It!” with a snatch of the headline. (After yelling themselves hoarse, the newsboys’ cry reputedly sounded like “Wuxtry! Wuxtry! Reed Allabatit! Japs Bomb Poil Hobbah!”)

The technology of color printing, used extensively by the Illustrated London News, was beyond technical and budgetary possibilities of daily papers until the 1890s, as was the ability to reproduce photographs as halftones. (The New York Daily Graphic was an exception, pioneering halftone printing in the 1880s.) William Randolph Hearst employed red and blue inks on white newsprint to produce a patriotic effect for major stories during the Spanish-American War of 1898. He and his rival Joseph Pulitzer were already printing the Sunday ‘funnies’ in full color at the same time. By World War I, Sunday supplements employed both color printing and the artistic ‘rotogravure’ process on a regular basis.

Full color daily papers became commonplace after the introduction of USA Today in the 1980s. Today, even small town journals regularly employ color presswork on a regular basis, thanks to computer graphics and layout tools and sophisticated presses. In the past couple of decades, the unwieldy large folio size has shrunk to more manageable dimensions.

Whatever forms news dissemination may take in the future, the traditional ink-on-newsprint papers have left an impressive and colorful legacy of mythic images: crusading small-town editors, hard-boiled newshounds slamming the keys of their clattering typewriters in a smoke-filled office, copy boys scurrying through the chaos of the City Room to the cry of “Hold the presses!” and trucks pitching out a bale of papers at the feet of a crippled ‘newsie’ at his flimsy newsstand.

In movies there is Orson Welles as newspaper mogul ‘Charles Foster Kane,’ reading his mission statement to Joseph Cotten and Everett Sloane in his Citizen Kane (1941); Pat O’Brien and Adolph Menjou in The Front Page (1931); or Cary Grant and Rosalind Russell in His Girl Friday (1941).

Yet, the aroma of damp printer’s ink and fresh newsprint cannot be replaced by the faint plastic and ozone smell of a hot computer screen.

In movies there is Orson Welles as newspaper mogul ‘Charles Foster Kane,’ reading his mission statement to Joseph Cotten and Everett Sloane in his Citizen Kane (1941); Pat O’Brien and Adolph Menjou in The Front Page (1931); or Cary Grant and Rosalind Russell in His Girl Friday (1941).

Yet, the aroma of damp printer’s ink and fresh newsprint cannot be replaced by the faint plastic and ozone smell of a hot computer screen.

As the novelist John Barth once observed, the only true ‘virtual reality’ is the magic combination of ideas, paper, ink and the reader’s imagination. By interpreting abstract symbols, the human mind can visualize scenes and grasp concepts without the sensory input of auditory or visual stimuli. The other sort is merely a synthetic reality, using artificial means (CGI) to fool the senses. Newspapers are the rough drafts of history and can be used to trace evolving knowledge of, and attitudes towards, a given topic. Online news is the true ephemera – here today and blipped out of existence tomorrow. It exists as shifting patterns of pixels on a screen, subject to instant updates and deletions, and dependent on a source of electricity. On the other hand, the specimens of antique newspapers used to illustrate this post have lasted for centuries in relatively good condition – hardly ephemeral. Unfortunately, after about 1880, paper made of highly acidic wood pulp replaced the more expensive cotton and linen rag paper. Wood pulp tends to self-destruct when exposed to heat, moisture and direct sunlight. Ironically, the papers printed from the 17th through the early 19th century will continue to exist long after the ‘modern’ papers have crumbled into brown chips.

1945

2008

2004