by John Adcock

♠

Masthead: The Penny Satirist No 1, April 22, 1837

‘I wish we had an agent in Dundee; he might sell five or six hundred (Penny Satirist) in a week. We have fellows who clear 10s. a day by selling them in the street, but the brutes go idle the rest of the week.’ — James Elishama “Shepherd” Smith, 1801-1857

The Penny Satirist, which called itself “a weekly satirical newspaper” featured the first sustained use of front-page political cartoons in London. The first number of the Penny Satirist arrived in the streets of London on April 22, 1837. That title came to an end on April 25, 1843, and the paper was continued as the London Pioneer. Benjamin Cousins was the printer.

William Rayner writing in Notes & Queries,

June 15, 1872, identified the editor as Barnard Gregory, notorious proprietor of the blackmailing periodical The Satirist. He

was mistaken. The founder and editor of the Penny Satirist was James

Elishama Smith (1801-1857), known as “Shepherd” Smith after his periodical the Shepherd.

For many years he was editor of the popular Family Herald story

paper. Mr. Newton Crosland wrote, presumably to W.A. Smith on 17th April 17,

1892: —

‘I cannot tell you much about the Penny

Satirist, and I do not imagine that the authorities would find room in the

museum for such a publication. Of course, fifty-four years ago a penny paper

was a much rougher article than what we should expect to get for the same money

nowadays. The Penny Satirist was one sheet (4 pages), the size of an

ordinary newspaper; but it was not a newspaper in the ordinary acceptation of

the term, as it was exempt from the newspaper stamp, and it did not live on

advertisements. The type was worn, the paper common, the woodcuts coarse, and

its whole appearance vulgar and disreputable from an artistic point of view;

but under Mr. Smith's superintendence nothing was allowed to appear in its

columns of a demoralizing character. He managed to make its contents

respectable.’ — “Shepherd” Smith the Universalist

[p.168]

And on November 3, 1837, a letter

from James E. Smith to his elder brother John —

‘The Penny Satirist has been above 40,000 a

week, but several scamps have tried to put us down—some by stealing our name,

and others by a rival publication and underselling. We have been obliged to

lower our prices to put the latter down, otherwise it would be a fine property.

It has a fine circulation and is read by all classes.

I was told by a gentleman, who is intimate with

some of the foreign embassies, that in dining at Buckingham Palace this

ambassador said he saw the Countess of Leiningen, the Queen's sister-in-law, with

the Penny Satirist in her hand. This same gentleman sends regularly a copy to

the Duchess of Somerset, and this morning the gentleman who machines the paper

—a large printer in London, who is worth considerable property —told me that,

in calling on a barrister of good practice in town, he saw the Penny

Satirist, with other papers, lying on his drawing-room table. The

circulation of the paper, therefore, is not confined to the poor, although they

are our best patrons. We have every reason to believe that the Queen herself

has frequently read it.’ — “Shepherd” Smith the Universalist [p.168]

The Penny Satirist was not the first periodical

resembling a newspaper to make use of comic woodcuts. The earliest publications

containing comic cuts I have found listed was The Original Comic Magazine:

No. 1, With Seven Cuts which cost 6d and was published by another radical

pressman, J. Duncombe in 1832. The famous penny blood publisher Edward Lloyd

published a penny paper called The Weekly Penny Comic Magazine; or,

Repertory of Wit and Humour, edited by Thomas Prest and featuring the cuts

of the prolific C. J. Grant, also in 1832. Unfortunately, I have never

personally examined either of these publications, they exist today only as

advertisements in the Poor Man’s Guardian and other radical newspapers.

The Satirist; or, Censor of The Times (HERE) ran from

10 April, 1831 to 15 December 1849. Barnard Gregory and Hewson Clarke were the

main contributors. Robert Cruikshank, brother of George Cruikshank and engraver

G. Armstrong contributed a political cartoon series called ‘Our Portrait

Gallery’ beginning January 4, 1835, which continued for approximately one year.

Gregory was the registered proprietor, printer and publisher at no. 334,

strand, Middlesex.

‘Our Portrait Gallery’ were comic cuts with long rhyming text

under the engravings, following the form of the early comicalities in Bell’s Life in London. The Penny Satirist was different, they placed conversational

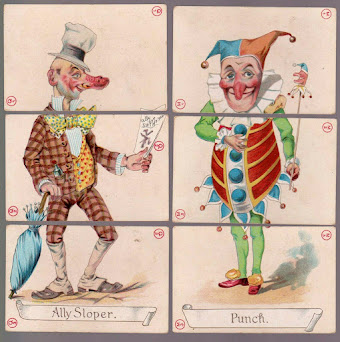

captions under the cuts. They anticipated the cartoon “socials” of Punch,

Judy, and similar comic journals of a later time. The style was carried on by the Odd

Fellow (HERE), a weekly

satirical newspaper which lasted from Jan 5, 1839, to Dec 10, 1842. The Odd

Fellow publisher was Henry Hetherington, a radical pressman famous for

his Poor Man’s Guardian.

Cleave’s London Satirist & Gazette of Variety began on

Oct 14, 1837, changed to Cleave’s Penny Gazette of Variety then Cleave’s

Gazette of Variety ending Jan 1844. The proprietor of the unstamped paper

was John Cleave, wholesale bookseller and newsagent situated in Shoe Lane. Patricia

Hollis in The Pauper Press (1970) wrote that at “the beginning of 1836 Cleave’s

Gazette was thought to have a circulation of 40,000.”

The leading caricaturist, and possibly the inventor of the

caption style that replaced rhymes, was Charles Jameson Grant. Mathew Crowther

wrote on Yesterday’s Papers on Feb 28, 2011 (HERE), that

‘From 1837 onwards most of Grant’s output was

confined to the pages of the Penny Satirist and Cleave’s London

Satirist & Gazette of Variety. Interestingly Grant and Cleave also

launched a separate, short-lived, broadsheet called Cleave’s Gallery of

Grant's Comicalities which doesn't seem to have run to more than a few

editions in 1837 and which focused on whimsical social humour rather than politics.

CJG was the most conspicuous signature to appear on cartoons

in both the Penny Satirist and Cleave’s. Indeed, very few other

names appear on the cuts except for Hine. It seems very

likely, given his prolific contributions to the unstamped penny press that CJ

Grant was the innovator of the caption style commentary running under comic cuts in the radical London Press which would carry on well into the

twentieth century in London and the United States. Even Hearst’s Journal

comic supplements featured caption comics on Sunday amid the works utilizing

balloons or dumb show. It could also very well be that captions were imported from continental Europe and its newspaper and periodical equivalent to the penny press.

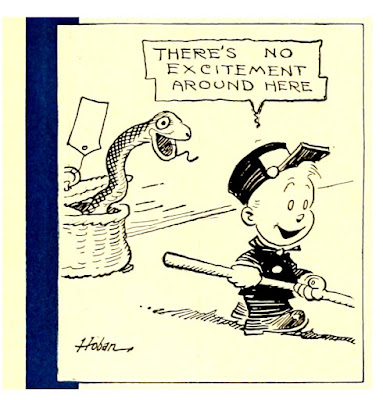

The captions in the Penny Satirist at first could run

to long length and it was the unknown caricaturists of the Odd Fellow

who shortened the form to bite-sized portions of text, more often “social” than

political humor, rather like the gag cartoons and single-panel dailies of the

twentieth century. It was the style of the Odd Fellow cuts that would

prove most adaptable to the pages of the comic journals (including Punch) and newspapers of the

unforeseeable future.