|

| [1] Ironclad Ned Kelly. |

We have no hesitation in saying that the life of Ned Kelly, the Ironclad Bushranger, is as disgraceful and disgusting a production as has ever been printed. Lord Campbell’s Act recognized the moral mischief which might be done by publications which offend against common decency, and provided for the condign punishment of the scoundrels who write print and sell them — they are, as the annals of the police courts prove every day, direct incentives to murder and robbery… — “Penny Dreadfuls,” in Saturday Review of Politics, Literature, Science and Art, Nov 26, 1881

The Otago Witness reports that the Salvation Army in Dunedin recently held a “novel-burning night,” which attracted a large army to the fortress. In the center of the ring on a bier were placed “yellowbacks” of all kinds, ranging from “Bluecap the Bushranger” to some of Besant’s works. — Barrier Miner, Broken Hill, NSW, March 30, 1894

—

THE FIRST PENNY NUMBER of Ned Kelly, the Ironclad

Australian Bushranger was published in the month of

July, 1881, by the London Novelette Company. By November the penny numbers had “attained an immense circulation.” The subsequent collection of bound penny numbers was preceded with fake quotes of praise from the Times, the Telegraph and the Press. Other bound copies survived published by Alfred J. Isaacs and General Publishing Company. All three publishers seem to have been one and the same. The author of the serial was unnamed but an unlikely subtitle reveals its text is written “by one of his captors.” What follows is Kelly’s encounter with the celebrated Spanish dancer Lola Montez when he has stopped her stagecoach on a moonlit night —

“Lola Montez, Countess of Lansfeldt,” said he, “your destiny is to become

the wife of Ned Kelly, the King of the Australian bush. The parson shall marry

us at once, and then I’ll take you right away to your future home in the

mountain ranges. What do you say to my plan, countess?”

“That I haven’t so much as seen your face. How can I tell whether I shall

like you? I have shown you mine; ‘tis but fair that I should behold yours in

return.”

“Well I don’t know but what it is.” And the bushranger dropped his reins on

his horse’s neck, and raised his ponderous iron head-dress.

Hardly had he done so, however, when the beautiful woman (we have her

portrait before us whilst we write) pulled a small pistol from within her

sleeve and fired it point-blank at the bushranger’s face, accompanying the

action with the contemptuous remark —

“Where seven men sit panic-stricken before a single villain, ‘tis time for

a woman to show what she can do.”

Unfortunately the beautiful specimen of the sex in question had not done

nearly so much as she intended.

The little bullet from her almost toy weapon, instead of penetrating the

bushranger’s brain, had only shorn off a portion of his left ear.

RUBBER-FACED BURGLAR. Another improbable character was introduced later in the text — Charles Peace, the rubber-faced British burglar. The author of Ned Kelly was James Skipp Borlase (1839-1902), who used the pen name J.J.G. Bradley in a series of penny dreadfuls published by Hogarth House in the 1880s. Borlase had already narrated his own supposed experiences with criminals, gold diggers and aborigines in his first nonfiction collection, The Night Fossickers and other Australian Tales of Perils and Adventure (London: Warne, 1867), and had supplied serials for several Australian bush papers. He’d left Australia in the 70s, bound for England via America, after writing some of the outback’s formative

detective fiction.

—

|

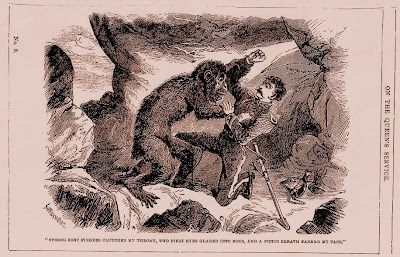

| [2] Town and Country Journal, July 10, 1880. |

DEATH MASK. Ned Kelly was hanged on November 11, 1880. The authorities, probably under the influence of criminal anthropologist Cesare Lombroso, took his death mask for posterity. The death mask was later brought out for show at the Institute of Anatomy, Canberra, in September 1951. On April 12, 1929, at the old prison grounds workmen with a steam-shovel unearthed a gruesome discovery, the skeleton of Ned Kelly.

The bones, which were remarkably well-preserved, were taken by workmen to

be kept as mementos. Mr. H. Lee, a contractor, of Richmond, secured the skull.

There was a complete set of teeth in the upper jaw but morbid souvenir hunters

removed most of them. — The Western Mail,

April 18, 1927

J.P. Quaine, an antiquarian bookseller of South Yarra, Melbourne,

Australia, wrote to penny dreadful collector Barry Ono that

The crowd fought amongst themselves like hungry dogs over the bones of the

fifty years buried outlaw. They burned them up with the steam shovel during

alterations to the old Melbourne jail, also Deeming’s body. The latter was

scrambled for by women, above all! I must confess that Australians are a race

of bloody savages.

|

| [3] Hogarth House Edition 1880s. |

BEFORE NED KELLY. James Skipp Borlase had written an early bushranger romance In London, as J.J.G. Bradley. Bluecap the Bushranger; or, the Australian Dick Turpin commenced in Charles Fox’s The Boys’ Standard, Vol. 1, No. 25, published in April 1876 as “Written by a retired Victorian Trooper.” Bluecap the Bushranger; or, the Australian Dick Turpin was reissued in 11 penny numbers by Hogarth House in the 1880s. Short as this penny dreadful was it would prove to be popular fare and was still circulating, described as a yellow back in Australia in 1895.

Like Ned Kelly, Bluecap or Blue Cap — an alias for Robert Cotterell — was a real person, a hunted bushranger captured at Humbug Creek in November 1867. Bluecap and a companion, astride stolen horses, had robbed a Chinese man at gunpoint for a measly two or three pounds and a pocket-handkerchief. He was sentenced to 10 years “on the roads.” The police constables called him “Bluey.” There was a second Blue Cap, several years later, but it was Cottrell, the original Bluecap, who was in the newspapers while Borlase was residing in Melbourne. No matter, Borlase dispensed with the facts and fashioned a thrilling and violent highwayman romance that was both funny and horrible to read.

He wore on his head a cap of bright blue cloth, fitting close like a

skull-cap, and with two long lappels that fastened under his chin. From the

summit of this cap stood erect a dozen or so of bright crimson and blue feathers,

to a height of nearly a yard. It was easy to be seen that they consisted of the

entire tail of a blue mountain macaw.

This singular head-dress covered the whole of his shaven skull, and gave

him a half-Indian, half Morisco, and wholly savage and demon-like appearance.

“I have been tailoring as well as plundering,” he said with a laugh. This

old cap, made to keep a traveler’s ears warm in a colder climate than this,

will give me a name, and in return I will give it a name. Henceforth I am

known, and known only, as

‘BLUE CAP, THE BUSHRANGER!’

Within a month or two Australian mothers shall hush their brats to sleep

with the terror of that name.

|

| [4] The Boys of New York, 1876, courtesy Joe Rainone. |

Norman Munro reprinted Bluecap the Bushranger; or, the Australian Dick Turpin shortly afterwards in the American story paper The Boys of New York, beginning in Volume 2, No. 60. October 9, 1876. His serials in the weekly proved so popular that J.G. Bradley (who was J.G.G. Bradley at Hogarth House in London) became a house name for American authors of an endless variety of serials, some good and some indifferent.

AFTERWORD. I once came across a book called Stirring Tales of Colonial Adventure; A Book for Boys by Skipp Borlase with illustrations by Lancelot Speed, F. Warne, London, New York, 1894. It was another version of The Night Fossickers, where Borlase claims to have known many convicts and criminals, and enjoyed their company. It identified Skipp Borlase as author of Daring Deeds, Tales of the Bush, Yackandandah Station and The Mysteries of Melbourne. On January 27, 1870, The Mysteries of Melbourne began circulation as a newspaper serial by “Kelp.” You can view Chapter one HERE.

|

| [5] London: Alfred J. Isaacs Edition, 1881. |

—

Read Bluecap the Bushranger;

or, the Australian Dick Turpin — HERE.

Read Ned Kelly, the Ironclad

Australian Bushranger — HERE.

NOTE: The two links above which were live at the time of posting (April 17, 2016) appear to now be available only by subscription. See HERE.

/¡\