|

| [1] The Harkaway Empire League — membership certificate. |

by E.M. Sanchez-Saavedra

Back in the early 1990s I blithely decided to investigate a series of very popular Victorian-era adventure stories about a character with the catchy name of ‘Jack Harkaway.’ The stories were credited to someone with the improbable monicker of ‘Bracebridge Hemyng’ — obviously a pseudonym. At the time, I owned a stray Harkaway story in Frank Tousey’s Five Cent Wide Awake Library, a group of Street and Smith paperbacks in the Harkaway Library, and an odd hardback volume from the 15-book series published by M.A. Donohue & Co., Harkaway Series for Boys. My intent was to compile a short cross-indexed bibliography of the original fifteen stories, prefaced by an even shorter blurb about the obscure author. It seemed a fun thing to do. I expected the research to take a year or so and result in a modest article in Dime Novel Round-Up or a similar journal. Ha!

Two decades later, I have nearly 500 pages of typescript, an extensive collection of variant Harkaway editions and a couple of thousand pages of notes, including detailed biographical and genealogical information on the very real English writer Samuel Bracebridge Heming (signing as ‘Bracebridge Hemyng’) who lived from 1841 to 1901 in England and America. Not only did he pen the Harkaway stories, but also a wealth of adult and juvenile fiction and non-fiction.

Until James Bond and Harry Potter, the fictional schoolboy adventurer Jack Harkaway was the only major English publishing phenomenon for adolescents on both sides of the Atlantic. The original stories, written in 1871-80, spawned imitations, were ‘pirated’ extensively, were adapted for the stage (and an early silent film) and remained continuously in print until 1933. More recently, they have become available in e-reader formats and from ‘print-on-demand’ venues. They were praised by Graham Greene and excoriated by Rudyard Kipling. ‘Harkaway’ became a generic term for blood-and-thunder adolescent reading and formed the basis of at least one publisher’s fortune. ‘Jack Harkaway’s’ creator has begun to emerge from the oblivion of more than a century.

Most English literary hacks, or ‘penny-a-liners,’ of the 19th century lived fairly anonymous lives: born into poor or lower middle class families, spending their days in rented rooms and pubs, and often dying young from alcoholism or malnutrition. Despite feats of literary athleticism that would exhaust modern writers, their labors were poorly rewarded – only a few earned as much as two pounds (approximately ten dollars) per week in flush times. In an act of bravado they called themselves ‘Bohemians.’ A few came from good homes (and very occasionally the minor gentry or nobility) and possessed more than a common education. These were the (non-inheriting) second or third sons, or inveterate gamblers or drinkers, who were unable to hold down a steady job. Some were just plain unlucky. Although they jumped through all the proper hoops, success in business or a profession eluded them at every turn.

With the shining example of Charles Dickens, who rose from a wretched childhood to become the literary darling of the English-speaking world, as a goal, dozens of impoverished hacks dreamed of writing David Copperfield or Bleak House while churning out The Jolly Dogs of London or Lives of the Most Notorious Highwaymen, Footpads and Murderers. Many of their serials and novellas were exciting and entertaining. Many were poorly written, badly plotted and peopled by cardboard dummies. A superior ‘penn’orth’ of fiction was one that contained more words than its nearest competitor. Quantity was everything in the early days of the penny ‘bloods.’

SAMUEL BRACEBRIDGE HEMING, if not born with the proverbial silver spoon, was born with a tastefully respectable plated article to a family of minor Warwickshire gentry. One grandfather, George Heming, was a well-to-do Jamaican sugar planter who married an heiress, Miss Amecia Bracebridge. The other grandfather, Henry Dinham Chard, was a master naval designer and shipbuilder.

Young Samuel’s parents were a May and December couple who saw four of their five children survive to maturity. His father, Dempster Heming, born in 1778, studied at St. Andrew’s University in Scotland and was called to the Bar in the Middle Temple in 1808. He set out for India in 1810, becoming the Registrar of the Supreme Court of Judicature in Kolkata (Calcutta), and returned in 1822 to his family estate of Caldecote, near Nuneaton, Warwickshire. He married for the first time at the age of sixty to one of his tenants, a lady half his age: Miss Rhoda Mary Chard. Their eldest son and heir was born in London on March 5, 1841. At some point, Dempster lost most of his fortune, and the family left Caldecote and moved to his elder brother Samuel’s Lindley estate in 1846. In 1856, following the Rev. Samuel’s death, Vincent Eyres purchased Lindley. Dempster Heming and his family moved to London, where he owned a house in Loughborough Street, Brixton, one in Bayswater and one at 70, Lower Harley Street, Cavendish Square, London. In 1860, his residence appears in the census as Barnes, Surrey.

Each of his three sons received a sound public school education – Samuel B. attended Eton College, Dempster, Jr. went to Winchester College, while Philip Henry studied at Harrow. While still in his teens, Samuel adopted the nom de plume ‘Bracebridge Hemyng’ for articles in the radical press. (His father held radical views and ran unsuccessfully for Parliament in 1832 on a radical platform.) He even penned a couple of amateurish novels and a scathing study of prostitution while studying for the Bar at the Middle Temple, to which he was admitted in 1862. So far, so good – a dutiful son who played by the rules and followed in his elderly father’s footsteps.

For some reason, his legal career was a total flop and he soon became known as ‘Briefless Bracebridge.’ Thanks to an accident of geography, his empty chambers were adjacent to Fleet Street, home of the bustling cheap publishing trade. Barristers and ‘Grub Street hacks’ rubbed elbows at a score of pubs along with publishers and journalists. In this atmosphere, not a few unsuccessful barristers tried their hand at cheap fiction to eke out a living. Just as Arthur Conan Doyle would begin to write detective stories in his empty surgery in the 1880s, young Brace Heming filled up his idle hours with producing novels for the new genre of ‘railway literature’ – paperback novels sold at train station kiosks.

Bracebridge Hemyng, a gifted storyteller with a ready imagination and ferocious energy, turned out dozens of ‘yellowback’ novels, short stories and serials for a wide variety of publications. Most were respectable, but some drew on his earlier researches into prostitution. He established a reputation for reliability and was often called upon to complete missing serial installments for defaulting fellow authors. In 1871, while working for Boys of England publisher Edwin John Brett, he created the character of Jack Harkaway, which caught on with the public and became as popular as Harry Potter would become over a century later. Brett only paid him two pounds a week, so he was ready to leave should anything better should turn up. Something did in 1873.

The flamboyant Anglo-American publisher Frank Leslie (born Henry Carter, in Ipswich, 1821) offered Heming $10,000.00 a year (he was then making about $500.00) to come to New York and write exclusively for him. From December 1873 to early 1880, Hemyng was a one-man fiction factory for Leslie publications, in addition to ghostwriting factual articles. In attempting to emulate Leslie’s gargantuan lifestyle, the barrister-turned-novelist ran through his huge salary. After Leslie went bankrupt in 1877 and died in 1880, Heming returned to London with no fanfare and returned to his two-pound-a-week drudgery for E.J. Brett and others. In the days before literary agents, he sold his work outright and received no royalties.

In 1884, his health failed. Suffering from malaria and a facial neuralgia so severe as to cost him an eye, he soldiered on for the next fourteen years, dictating his stories to Bessie, his third wife, as he was forced to sell all his furniture and move to ever-poorer lodgings. On several occasions, he applied for relief from the charitable Royal Literary Fund. His final serials about ‘Harkaway the Third’ set his hero’s grandson in the Boer War of 1899-1900.

Heming died of paralysis on September 18, 1901 in a dingy flat in Fulham, London.

Besides the large volume of writings that he produced between 1860 and 1901, there are a surprising number of physical and documentary landmarks relevant to Samuel Bracebridge Heming’s life. Some of them exist to this day.

Because past researchers were unable to locate a birth certificate, it had been speculated that he was born outside of the U.K., possibly India or Malaya. However, in the April, 1841, issue of The Gentleman’s Magazine, by Sylvanus Urban, Gent., Volume XV, New Series, MDCCCXLI, January to June Inclusive, p.143, we find the following terse item in the birth announcements under ‘Lately’ (i.e.: March, or early April, 1841):

In St. James’s-st. the wife of Dempster Heming, esq. of Caldecote-hall, Warw. a son and heir.

|

| [17] Gilsey House cigar box label. |

Mr. Heming married in 1839 Rhoda Mary, third daughter of the late Henry Dinham Chard, Esq., merchant, of Lyme Regis, Dorsetshire, by whom (who survives him) he has left a family of a daughter and three sons, the eldest of whom is the well-known novelist, Mr. Bracebridge Heming.

|

| [18] The Gilsey House in New York today. |

The sugar plantation owned by his ancestors in St. Ann’s Bay since the 17th century still exists as a Jamaican Heritage property. Built originally by Captain Richard Heming (died 1692) on land once colonized by Columbus as ‘Sevilla la Nueva,’ the Seville Great House is a major archeological site and tourist attraction.

Grandfather George Heming died in 1804, leaving Weddington and Lindley manors to his eldest son Samuel, and Caldecote to Dempster. A manor since 1086, the house was burned by Prince Rupert in 1642, when it was owned by Col. William Purefoy, a ‘Roundhead.’ Purefoy later signed King Charles’ death warrant. The Heming family home at Caldecote incorporated some of the original structure, but was extensively remodeled by Capt. Henry Townshend in 1880, during the ‘Gothick’ revival craze of the late 19th century. After Townshend’s death in 1896, it had a chequered career as a showplace residence, a C. of E. rest home for wealthy alcoholics, and ‘St. Chad’s’ school. It was severely damaged by fire in 1955. The East Wing is currently a posh condominium of 1 and 2 bedroom apartments. (See Country Life, August 4, 2005.)

St. James’ Church Weddington, in Nuneaton, where many of his family members are buried, still exists, although it also has undergone substantial remodeling. The Reverend Samuel Bracebridge Heming, the author’s uncle and namesake, served as its vicar. The earliest remains of an ecclesiastical building on the site date to the 14th century, but the baptismal font is a 12th century relic. The church was rebuilt in red brick in 1733 and heavily restored in 1881 with Gothic windows.

|

| [21] John Ludlow poem Jack Harkaway, 1902. |

In 1861, Heming studied law and dined at the Middle Temple, and was called to the bar on April 30, 1862, according to The Law Magazine and Law Review, or, Quarterly Journal of Jurisprudence, November 1861, to February, 1862, Vol. XIII (London: Butterworths, 7, Fleet St., 1862) p.381: ‘Calls to the Bar. Easter term 1862.’

The Middle Temple in London still looks much as it did when the briefless barrister twiddled his thumbs waiting for a solicitor to throw a case in his direction. Buildings damaged during the London Blitz have been painstakingly restored.

In December 1873 Bracebridge Heming and his bride embarked for New York aboard the Inman Line steamship ‘City of Brussels.’ Built in 1869, it was the first transatlantic steamer to be equipped with steam-powered steering gear. On January 7, 1883, she collided in the fog with the Kirby Hall of the Hall Line and sank in Liverpool Bay at the mouth of the River Mersey. Ten lives were lost in the disaster. Two years later, the Inman line sold out to the American and the Red Star steamship lines. The shipwreck not only still exists, but serves as a regular diving destination for the Merseyside Sub Aqua Club.

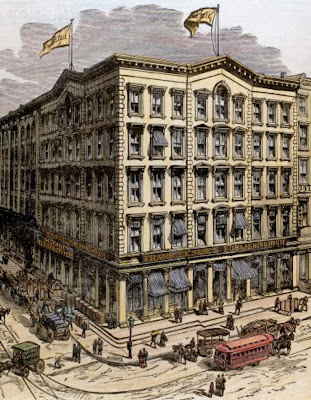

Upon their arrival in New York at the Inman Line pier, (which later burned in 1883,) to a riotous welcome stage-managed by Frank Leslie, the Hemings took up residence at the luxury Gilsey House hotel at Broadway and 29th Street in Manhattan’s ‘Tenderloin’ district. Other guests included ‘Diamond’ Jim Brady and George Armstrong Custer. The marble and cast iron showpiece, erected in 1871, has been restored to its former glory and, like Caldecote Manor, is currently a condominium.

After about a year at the Gilsey House, the Hemings moved to Staten Island, within sight of the Manhattan skyline. Briefly they resided at a boardinghouse run by an English family named Young. In 1875, the Youngs named their newborn son after the ‘famous author.’ The name ‘Bracebridge Hemyng Young’ has been passed down through the generations of the family. Their exact address, and that of the large house rented by the Hemings in Clifton, have not yet been pinpointed.

Frank Leslie’s Publishing House, located first at 537 Pearl St. and, after 1878, at Nos. 53-55-57 Park Place in lower Manhattan, was his nominal ‘office,’ although I doubt he spent much time at either location. Today, the Pearl Street neighborhood is dominated by the NYC Police Department HQ, the U.S. Marshals’ Services, the Metropolitan Correctional Center, the U.S. Justice Department and the NYC Supreme Court. Park Place is anchored to the east by the Woolworth Building and is the location of the Amish Market.

|

| [24] Heming biographies in Frank Leslie’s Boys of America, and in The Young Englishman (published by Hogarth House, London). |

After Heming’s ignominious return to London, specific places associated with him thin out rapidly. The ‘Olde Cheshire Cheese’ pub in Fleet Street was more than likely one of his haunts. Between extensive German bombing during the Second World War and massive postwar urban renewal, the Battersea and Fulham neighborhoods in which he spent his final years are unrecognizable. Battersea retains some of its industrial character, but erstwhile shabby Fulham has become extremely gentrified, fashionable and expensive.

AN APPEAL

TO OUR READERSHIP!

TO OUR READERSHIP!

Detective work consists of lots of routine procedural slogging. Many cases are solved only when a ‘tip’ is provided by an unexpected witness. After researching the life and works of ‘Bracebridge Hemyng’ for the past twenty years, a number of questions and mysteries about the author, his family and places associated with him still remain. Among them are:

Q. How did his father lose his fortune? A tantalizing reference in the July 8, 1882 issue of The Builder states: ‘The way Mr. Hemming’s [sic] large fortune was dissipated is a matter of notoriety amongst readers of causes célèbres,’ but provides no specifics. Dempster Heming and his wife’s brother, Henry Chard, were seriously involved with an association of Spanish bondholders (and even sent money to support a Carlist pretender to the throne of Spain.) The Spanish government defaulted on its debt. Perhaps this is the cause celebre? Historical tidbits can be maddeningly coy at times.

Q. Where did the Hemings live in Clifton, on Staten Island? Bracebridge Heming’s first wife, Jane, died during their increasingly grim life in New York. At present, the only accounts of her madness and death from hypothermia are pure hearsay and ‘fudge’ such details as the exact date. She is supposed to have become deranged, attacking Heming’s guests and passers-by, and finally wandering out on a cold night, dressed only in a flimsy gown.

Q. Where is ‘Bracebridge Hemyng’ buried? In 1902, John Ludlow wrote in his poem in the New York Herald:

And nowhere on the starry peaks

And pinnacles of fame

Has time a proud memorial raised

To Bracebridge Hemyng’s name.

Too true. Surely, somewhere in London, a gravestone exists?

And nowhere on the starry peaks

And pinnacles of fame

Has time a proud memorial raised

To Bracebridge Hemyng’s name.

Too true. Surely, somewhere in London, a gravestone exists?

Q. Are there any portraits of him and his family? Do any paintings, sketches or photographs exist of his parents, Dempster and Rhoda, or of his brothers, LTC Dempster Heming of the Madras Police, and Philip Henry Heming, Royal Navy? An oil painting of his grandfather Henry Dinham Chard, commissioned by Dempster Heming, now hangs in the Lyme Regis Philpot Museum.

Q. Does any photographic portrait of him exist? The half-dozen or so images of Bracebridge Heming are all woodcuts of varying quality.

If sharp-eyed readers of Yesterday’s Papers can answer any of the above questions, a communication would be most welcome. (A response qualifies the respondent for immediate lifetime membership in the Harkaway Empire League of Health and Good Habits — plus my undying gratitude of course.)

I would really like to finish the research and whip my manuscript into shape for publication in book form, so any assistance, however small, assumes major importance to me.

•¡•

Thanks to Mr. Joseph Rainone, Mr. Robert J. Kirkpatrick and Mr. John Adcock for their generous help.

It appears Hemming was not averse to plagiarism, http://www.keeline.com/verne/ compares the characters and events in one of his stories to 20,000 Leagues under the sea in some detail...

ReplyDeleteSamuel BH was the brother of Philip Heming, editor of the notorious London Life. Philip's son, Jack Chetwynd Western Heming wrote juvenilia and his wife Eileen Marsh (aka Dorothy Carter etc) did too. Some were about flying, Wrens, Sea rangers and Girl Guides.

ReplyDeleteThanks!

ReplyDelete